A tribute to Norman J. James, designer of the Firebird III

Theme sketch that started it all.

Bill Porter is quoted to have said that the Firebird III is a ’50s theme with ’60s surfaces. That would explain at least in part the fascination I had with the car whenever I looked at it when it was on display in the Research Staff lobby. The creation of the car was shrouded in mystery to me until I read Norm James’ detailed account of how and why it was created. His book, Of Firebirds and Moonmen, is a must read for any designer. It opens up a world of design that was certainly unknown to me and unlike any experience I had at Design Staff. Many thanks to Norm James for the information and photos in this post.

In this post there is an excerpt from the book and photos from GM Styling including design and construction. Part 2 will include another excerpt from the book and a lot of photos from the Motorama filming at the Mesa Proving Grounds in Arizona (including many candid shots by Norm James). At the end of the post are links to the Firebird III brochure, additional excerpts on the GM Heritage site, a book review by SpeedReaders, where to purchase Norm’s book, and a link to an index of the book.

Excerpt from Of Firebirds & Moonmen

“If we don’t put fins on this car, then someone else will.”

Research Studio drew the assignment for designing the Firebird III because it was under Robert F. (Bob) McLean, who also headed the design of Firebirds I & II. The studio itself was new, created when Styling moved into the new Technical Center in 1956. At that time, the studio was set up with two designers, Stefan Habsburg, a graduate of MIT who’s specialty was mechanical and systems design and myself, a graduate of Pratt Institute and the “Styling” part of the team. We also had a studio engineer, Al Aldrighetti and two clay modelers; the modelers were out on loan to other studios.

Bob McLean would have been more involved with the actual design, as he was with Firebirds I and II, however, he elected not to. He advised Stefan and me of this in a closed-door meeting, saying that from now on he would participate only as a manager. He would give us an assignment and a date for completion. Then he would accept or reject what we presented to him, stating that it would be just like in a fine restaurant; if he didn’t like the food as it was presented, he would send it back to the kitchen to have it done right. He would not go in the kitchen and cook it himself!

Activity had actually begun weeks before, except it was then only known as “a car” for the next Motorama (a year and a half hence). We did not know if it would be a running car or a fiberglass dummy, like most of the Motorama cars were. Nothing further was defined so we started searching for a theme. We converged on a small electric car, developed as a clean simple form, devoid of fins and in good taste, i.e. a potato. We went so far as to build a full size mockup that you could sit in. The mockup was constructed of plywood templates mounted on top of a low wooden platform (on castors). It was like a flying model airplane, except without a skin.

A meeting was called with Mr. Earl to review it and McLean made the presentation, identifying all of its features. Earl patiently waited for McLean to finish and then, without addressing our presentation, began adding new information on the project that had already been committed to:

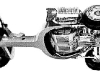

- The (Motorama) car would be a running vehicle representing the Corporation (rather than a Division) and that it would be the third in the Firebird series of cars—designated as the XP73

The body would be a two-seater, similar to the Club de Mer of the 1956 Motorama, except a little bigger, in order to handle all the special features

It would have an upgraded version of the Firebird II Wildfire regenerative gas turbine engine, mounted amidships

It would have a joystick controller, instead of a steering wheel, and an automatic steering system being developed by Research Staff, able to follow a wire in the roadway

It would also have an auxiliary power unit (APU). A small two cylinder 10 HP engine driving a 115 Volt AC electric generator and hydraulic pumps to run the accessories.

The novel feature was that on the show circuit, the generator could be run backwards (as a motor) on 60 cycle house current, to power all systems for show, and not have to run the APU engine indoors

Research Staff had already begun work on the chassis layout, sizing tires, wheelbase and track. We could expect to see preliminary drawings in about a week.

Mr. Earl then began describing the emotional side of the Motorama and what could be expected. He described how New Yorkers would wait in line, four deep, around the block just to get into the Waldorf Astoria to see the free auto show inside, in the Grand Ballroom. He wanted the people around the car to be so deep that they would have to stay for an extra show, just to get a better view (and also making for a more dramatic setting). The key expression he used that summarized everything was when he said, “You know, when you go to see a show in Las Vegas, you don’t expect to see your wife on the stage. You expect to see a real floozy.”

When Earl and McLean left the studio shortly afterwards, and based on his floozy comment, I looked at Stefan and said, “You know, if we don’t put fins on this car, then someone else will.”

Firebird III Styling Development

Firebird III clay model.

Photos courtesy of GM Media Archives

I began a series of sketches, trying to find a theme and drew from things I had seen at an air show at Selfridge Air Force Base (near Detroit) the summer before. One of the things that struck me was a Nike surface to air missile that I saw mounted on its launch rail. It was a two-stage rocket and had a set of four fins at the aft end of each stage. What struck me was that setting it on the rail required clocking the rocket 45 degrees so that the fins would clear. While not that unusual in itself, aerodynamic fins were normally thought of as vertical or horizontal.

Based on this thought, I made a simple sketch combining several of the other features I noted in the air show. The body had a “stove pipe” front end like the F100 fighter, only wider to span the full width of the passenger compartment. Because the front end only housed the APU, it did not need the full opening (height) of a large scoop. The Club de Mer roadster had two small windscreens for the passengers and I enlarged these to be full blisters. Behind these, and at the maximum body width, I introduced the quad fins, clocked at 45 degrees. It was a simple sketch but, in essence, it fulfilled Harley Earl’s vision.

With a general theme that seemed workable identified, I thought it was also a good time to try another idea that I had been considering for some time (a design technique). I had been concerned about the standard design routine used when starting new designs, i.e., sketching side views full size on vellum with a soft pencil. In practice, the designer would have to step back from time to time to see what the full view looked like. Necessarily he would have to erase some lines and draw new ones. My concern was that, in trying to assess what he had, erasure smudges would erroneously be contributing to the design, when they really shouldn’t be. I had thought of a technique that addressed this problem and decided this was the time to try it. I called the technique “string drawing.”

Stefan and I agreed that we would go with the quad fin sketch and try the technique. We ordered colored yarns and pushpins (which had to be purchased) and were waiting for them when we started receiving the wheelbase, tire and track data and profiles for the APU, turbine engine and trans-axle. We carefully positioned the profile templates onto our vertical boards (on gridded vellum) and added tire and our 95% Oscar templates.

With the arrival of the pins and yarns, we tied a small loop at the end of the first yarn and pined it to the board as the front of the first horizontal line. We then pulled the yarn to its end point, cut it and tied another loop…pinning that as the end point. There was enough elasticity in the yarn that we could take other pins and stretch that yarn (up or down) with enough pins to give character to the line.

The beauty of the technique was that by just observing the spacing of the pins and the rate of change in that spacing, it was possible to adjust it to a “mathematical purity” for line character. Secondarily, the eye could also judge the angle change between line segments, offering another basis for judgment. In total, this would be an aesthetic metric.

The pins also worked in another manner. Applied to the “form follows function” rule of design, say where a line approached a radiator corner, or other feature in near proximity, one could stage the pins to approach the feature in a regular mathematical progression and then on passing, flip to a retrograde reverse motion in a related regression of that sequence. It would be similar to astronomical physics, where bodies in motion are affected by the gravity of other bodies as they pass by.

String Drawing Technique with Norm James. “I heard that the string drawing technique was picked up and used for a short time in a few of the other studios, but it was quickly replaced by black 3M photo tape drawings because they had a stronger graphic impact. My personal preference remains with the yarn technique, precisely because it is more abstract and more perfectly defines lines in a present day digital [computer] sense.” Photo courtesy of GM Media Archives.

In this manner, we laid out the lines for the Firebird III following the noted sketch. We had a problem (which you always do when scaling up a sketch to full size). Our turbine engine was located behind the passengers and the rear wheels would be fixed by the trans-axle, some distance behind the turbine. This pushed the wheels further back than we wanted, behind even the quad fins. This left the rear body extending way too far back, with a long flat surfboard like overhang.

While I was staring at it, Stefan said, “What if we try something like this” and then walked up to the board and pinned a large central (dorsal) fin and lower fins extending outboard, even further aft. I was aghast…thinking, “You can’t do that! You can’t add a three element fin array behind the four fin quad array!” But, I didn’t say anything because it added the balance the design was crying for. I then went to the board and tweaked the lines a little bit. I stepped back to look at it again and thought, “This is starting to look pretty good.”

I then set up other vertical boards to develop a ½ plan, front and rear views. That was to get all the features (mostly fins) correct in all views. In the front view, I set up two passengers in a tight “sports car” like cross-section, leaving enough space to develop the quad fins within the 80-inch street legal width. …It was still looking good.

We called McLean to “Come take a look.” He had an office on the second floor of the administration building, down the hall from Earl’s office, and he said he would be right down. A few minutes later he was in our studio and appeared to be very pleased. The situation was this; when Earl described what he wanted, we began converting our original mock up to the Club de Mer roadster and we were committed to complete it. So, what McLean immediately did was authorize our building a second mockup to the new design. We would have to carry both mockups to a common level for presentation to Earl. My task would be to convert the string drawings to hard straight-line segments and then overlay a clean sheet of vellum to interpret an equivalent in hard line sweeps. I would then have to draw up all the sections as separate details and send them to the woodshop to be made for assembly (in notched egg-crate fashion).

I decided to do something else different for the mockup. As noted before, mockups were usually built up on gridded platforms. Templates were then mounted to the platform at ten-inch intervals, with the outside line following the exterior body contour and an inside “trim” line offset one inch inside (representing clearance for inside mechanical components.

What I wanted to do was to make a “space sketch” as our 3D sculpture mentor, Rowena Reed, had taught us at Pratt (to define a sculptural concept). To do this, I selected those sections that were most characteristic of the design and then shaped their inside trims to best enhance that character in those template details. The main change, however, was to get rid of the platform base. I replaced it with a deep section wood beam cruciform, mounted on four large castors. The templates would be mounted directly to that cruciform and it would lie entirely within the body profile, yielding “free (negative) space below.” The center beam almost implied a structural centerline spine (which the Firebird III ended up having). Two contoured lounge type seats were fixed tightly into the cruciform.

The drawings were completed and sent to the woodshop to have the parts made. As these parts started coming in, we had two woodworkers assigned to our studio and I had to be available to identify what the parts were and where they went, as I had made no assembly drawing. Some of the features like the nose lip and side air scoops were detailed more accurately and they were hand shaped in poplar wood and painted in a high gloss white lacquer. The intent was that these details were considered to be “dominant” design elements and I wanted the observer’s eye to “linger” on these details. The rest of the templates, after assembly, were hand painted in a flat light gray latex water-base paint. Unusual items like the blister canopies had to be represented by ½ inch wide template sections cut out of ½ inch Plexiglas sheet.

In this photograph, the mockup has been upgraded from the way it looked when Harley Earl “bought-off” the design. Plexiglas blisters were vacuum formed from casts taken off the clay model. Norm James is in the photo. Courtesy of GM Media Archives.

With the new model completed, McLean scheduled a meeting with Mr. Earl to review our progress. We never knew if Earl had seen our mockup in work, as it was rumored that he made the rounds at night and knew everything that was going on. On the day of the meeting, Earl walked into the studio at a brisk pace, and then turned in an arc, as he saw our new mockup, stopping along side it. With hands on his hips, he had a big smile. There was very little in the way of presentation or even discussion. This would be the Firebird III and he gave us the OK to “go to clay.”

Earl and McLean then left the studio as Stefan and I celebrated. McLean returned somewhat later and told us that Earl had directed the design committee to “stay out of our studio”—the end of a perfect day.

The noteworthy design message turned out to be that following the simple sketch, the string drawing that defined it and then its conversion into a “space sketch”; the design work was “done.” The long tedious process of getting the surfaces right in clay was just a matter of working the problem until it captured the essence of the mockup, which was there every day to be seen as a frame of reference. Even as the designer, I did not feel I had the right to change the basic architecture to solve some small problem that wouldn’t go away. I found that if you didn’t put too much effort in solving problems, they did not attract that much attention and flaws were not that big a deal. The design of the Firebird III was actually complete with the mockup. The execution took a little longer.

There were a few more events worthy of mention that happened leading up to the completion of the clay model. As noted earlier, Harley Earl had prohibited the design committee from entering our studio, but there was a conflicting incident that happened that summer. Earl went to Europe for a combined business trip and one-month vacation leaving Bill Mitchell in charge. Inevitably, Bill Mitchell and the design committee came by and offered their help. The committee was in complete agreement that the three rear fins were excessive and had to go. McLean was not able to dissuade them, so we removed them and cleaned up the surfaces, ending up with a long plain overhanging plank in back. The changes were completed in time for Earl’s return. We were placed on Earl’s busy schedule for a status review of the Firebird III. It would be in the auditorium so the model was transported down the long underground passageway and set up on the center turntable of the elevated stage. McLean and the design committee gathered around it and waited for Earl to appear. Stefan, Larry [Simi – the head clay modeler], and I, with a few other studio people huddled down below on the main floor, out of sight behind some boards. Earl finally arrived and took a position at center stage. McLean drew the task of presenting the change to Earl. McLean began his pitch. “After review . . . it was clear . . . we all agreed,” while Earl very quietly and politely waited for him to finish. After a pause, Earl began speaking. “You know,” he said, following with a pause, “when I came into the studio that day—for the first time—and saw the mockup . . . I actually saw the finished car in the Waldorf Astoria . . . and it was exactly as I had pictured it.” After another pause, he continued, “Now, why don’t you all take the car back and put it back to the way it was when I left.” With that, he turned and walked out.

If you want to read the rest of the story, get the book.

Firebird III Construction

Of Firebirds & Moonmen: A Designer’s Story from the Golden Age

by Norman J James

Xlibris Corporation, 2007

217 pages, 67 photographs, 43 illustrations

List price: $21.99

ISBN: 978-1-4257-7653-4

Purchase the book through Amazon

Purchase the book through Barnes & Noble

Links:

Download the Acrobat index of Of Firebirds and Moonmen

Firebird III brochure on Dean’s Garage

SpeedReaders book review

About the Author from Xlibris

Description of the book from Xlibris

Gary,

Thanks for the nice job of putting this together. I would like to add a few comments:

I elected to go the “Print on Demand” route for Of Firebirds & Moonmen because it allowed me to intermix all the graphics with the text, which gave better continuity. The penalty I had to pay (at the time) was the interior of the book had to be all in black and white (no color photos).

I appreciate the opportunity Gary offers in showing them here in color as there is nothing like a clear Arizona sky for showing automobiles. These photos have to be seen in color to fully appreciate them. That having been said, except for the book covers, all versions of the book interior are in B&W.

I would like to note that the book is also available in a soft cover version. You will usually find this option available in the same bookstore electronic search.

As of a few weeks ago, it is now also available as an E-Book.

Thanks, Norm

I ordered this book from amazon.com and it arrived in the UK within 5 days. Outstanding publication! This rates among the all time great engineering/design biographies, one to re re-read along with Ken Rudd’s ‘It was Fun’ or Vincent/Velocette engineer Phil Irving’s ‘An Autobiograph’. Norm James is a natural writer, conveys his passion for automobiles and astronomy onto the page with affection and respect for his friends and colleagues, is fascinating on his design education and the design courses at Pratt and describes the early days at Tech Center as though the reader is there with him. He has no old scores to settle, except perhaps with the design committee who lopped the lower fins off the Firebird III while Harley Early was away, but the put-down was Earl’s—you have to read it. The story of the Firebird III is epic, amazing and worth a movie, which of course they made at the time and hope will one day appear on youtube, or better still be embedded in the E-book version. If you love GM Design of the the ’50s and ’60s, this is probably the best book that will ever be written about the era. Thank you Mr. James.

To Tom Falconer,

Thank you for your kind words. I’m glad you enjoyed the book and I am especially pleased that you picked up on the things I was trying to do. It was reassuring, in that I was somewhat concerned about introducing tangential material into the story, but I felt that those things were fundamental in formulating and developing patterns of observation and interpretation in a budding designer. You have eased my concerns.

I would also like to note, regarding the story for representation of that era, secrecy permeated that culture, almost more so than I would find later when having Secret clearances. I had almost no knowledge of what was going on in the other studios, so I don’t know if my experiences were typical. I suspect that they were not. The secrecy was one reason I wrote the book; I recognized that there was a story there and I was the last custodian of that story.

With my best wishes, I thank you, Mr. Falconer for your comments.

Norm

Did anyone work with Al Atwell?

Hi Dean!

Love the article. Love the Firebird III. Here is my CGI Firebird III. Anyone have actual diagrams of the car? I built this from photos for reference.

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?vanity=doug.drexler.7&set=a.10157475239126104

I have see many a “dream car” in my day, but the Firebird is the only one I’d pay to ride in. A car that looks like a marriage of a spaceship (future) and a coelacanth (distant past) is so right it could never be wrong. My congratulations to the designer, and can I have a ride?