GM Designer Dennis Wright—From the Farm to the Wind Tunnel

by David Rodríguez Sánchez

Images: General Motors and the Wright Family.

Contemporary, homage renditions by Marc de Rijck and the author.

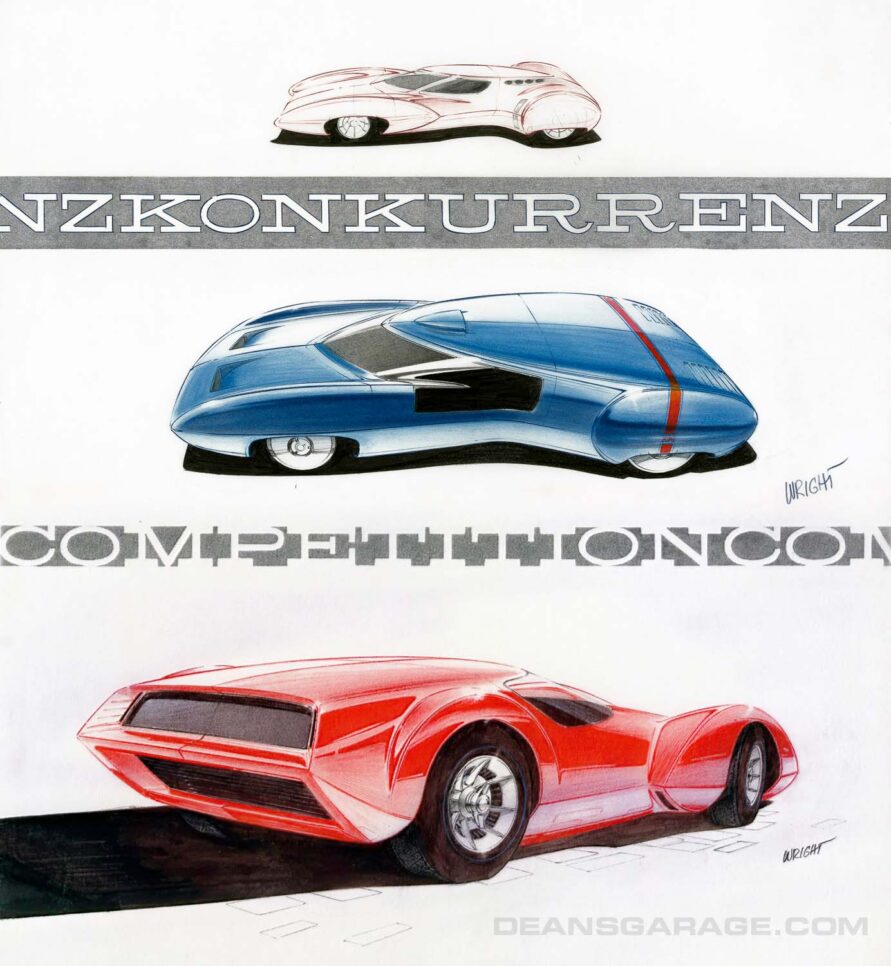

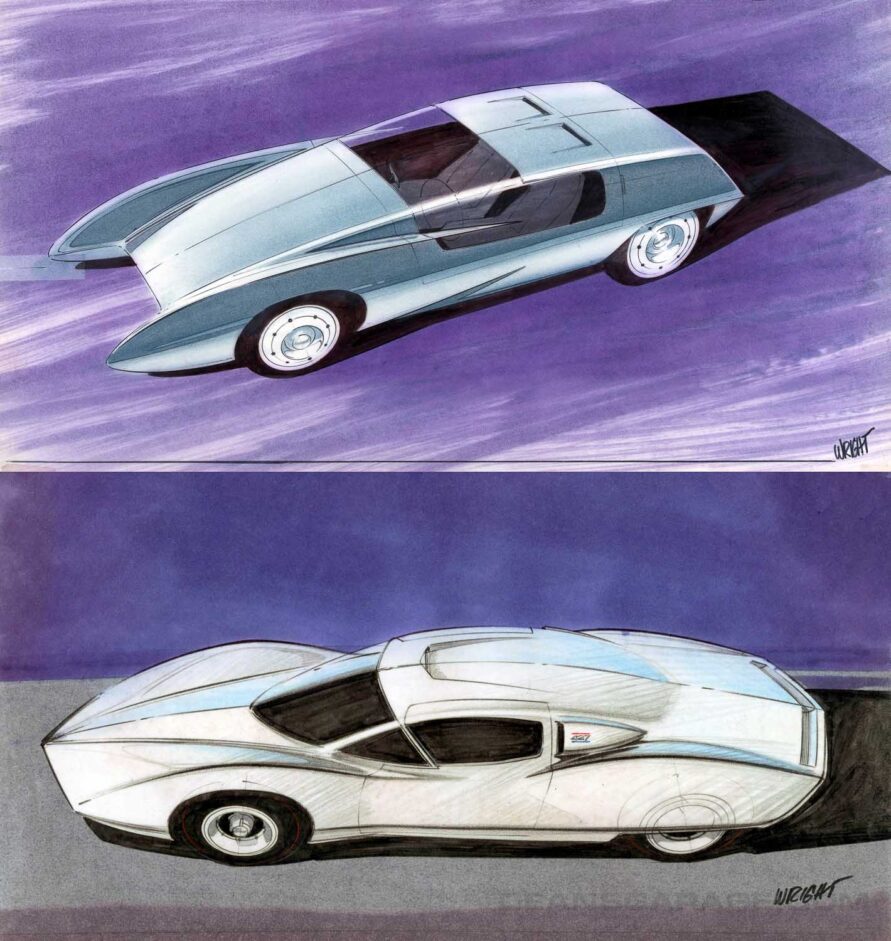

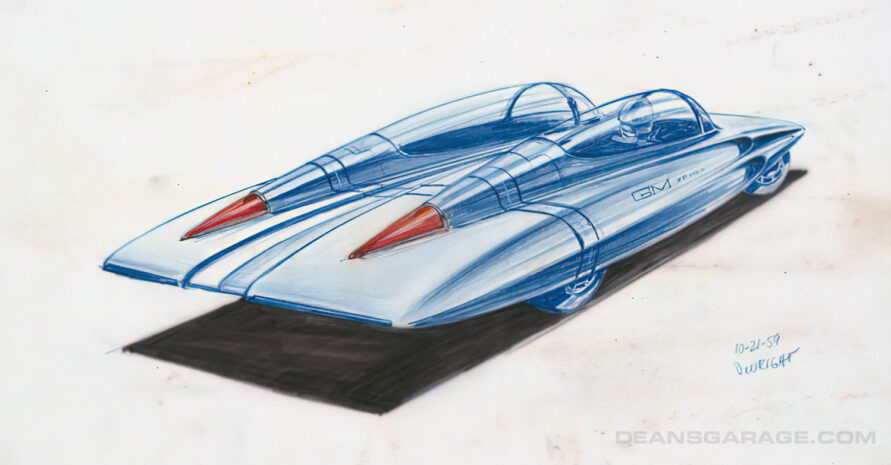

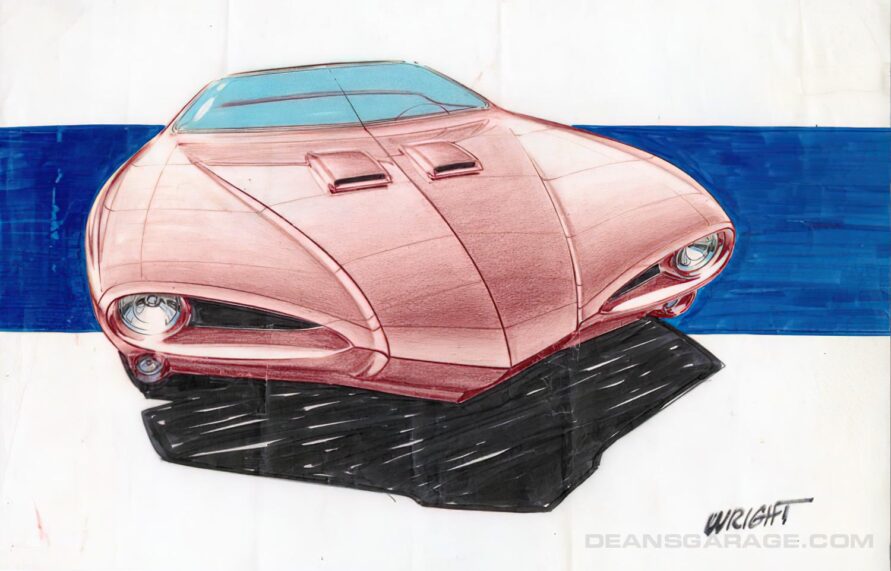

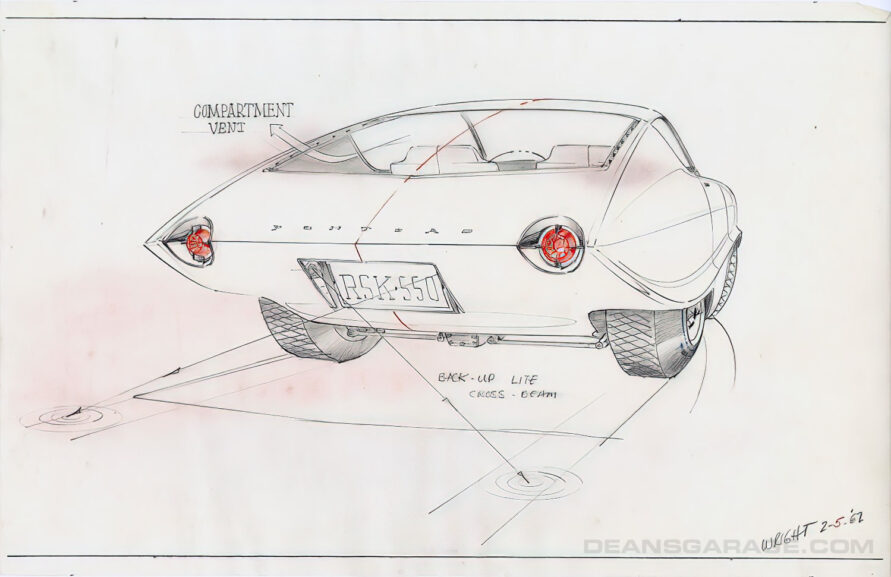

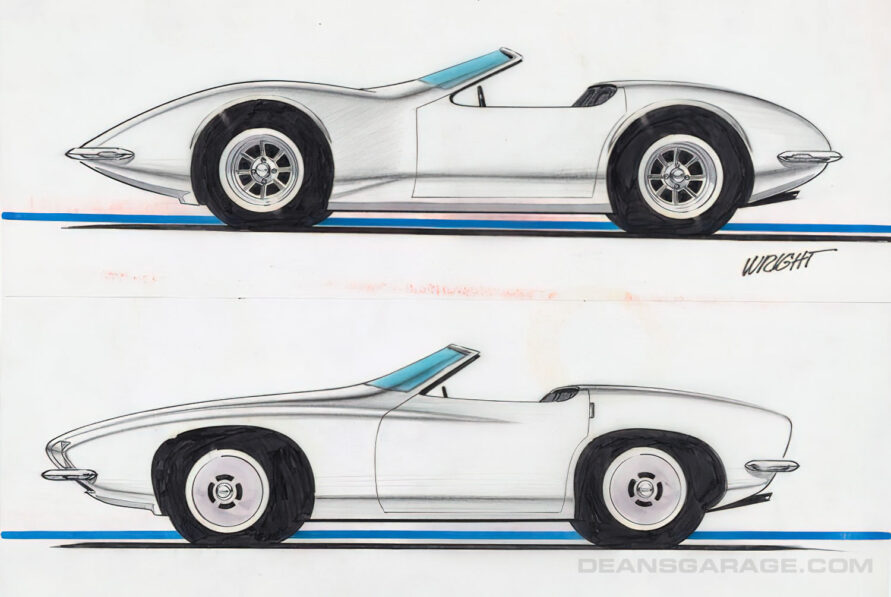

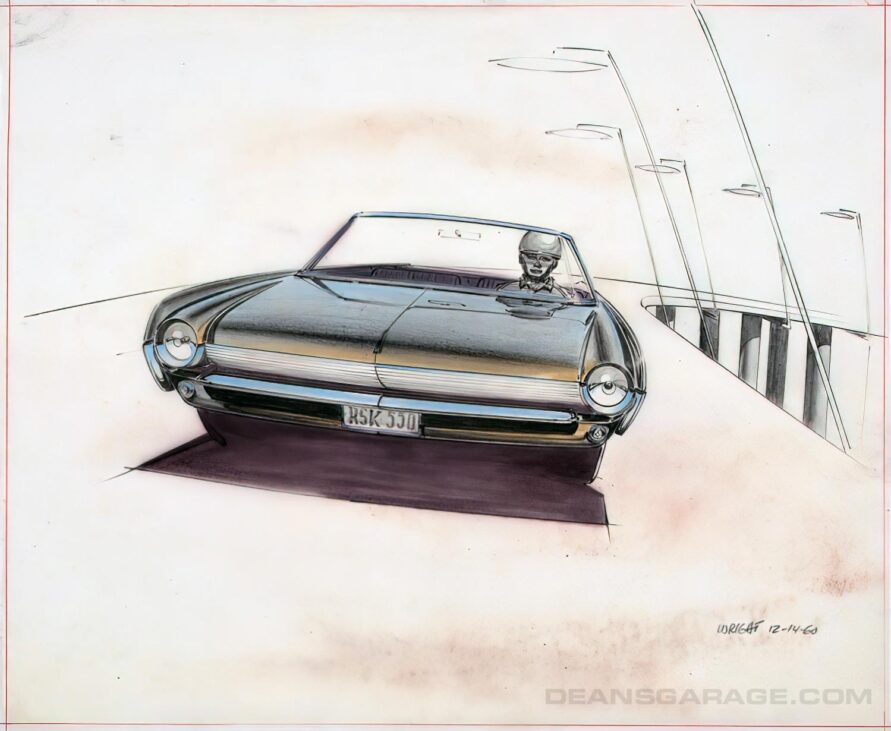

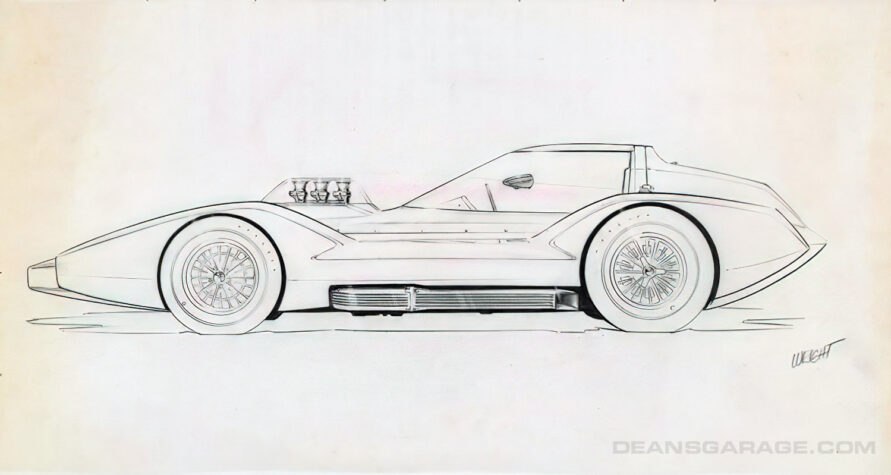

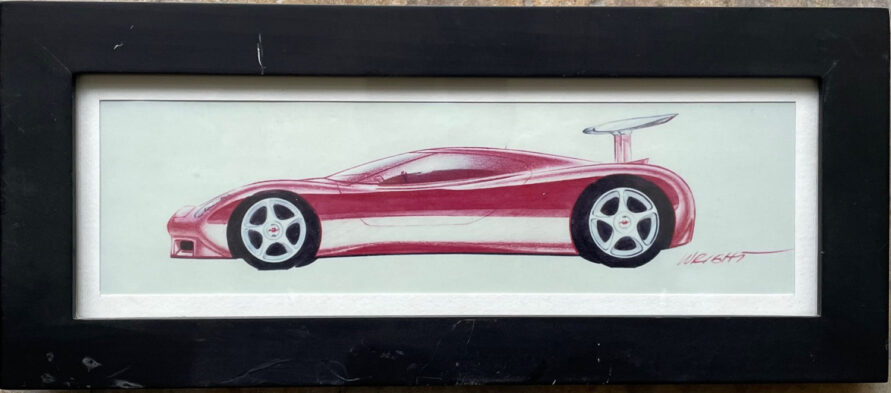

An exhibition titled “Competition, by Dennis Wright” was held internally at the GM Design Center in Warren, Michigan in 2021. A selection of twenty-two sports and competition car themes developed by Wright between 1965 and 1967 were displayed. Dennis had a 37-year career as a designer at GM.

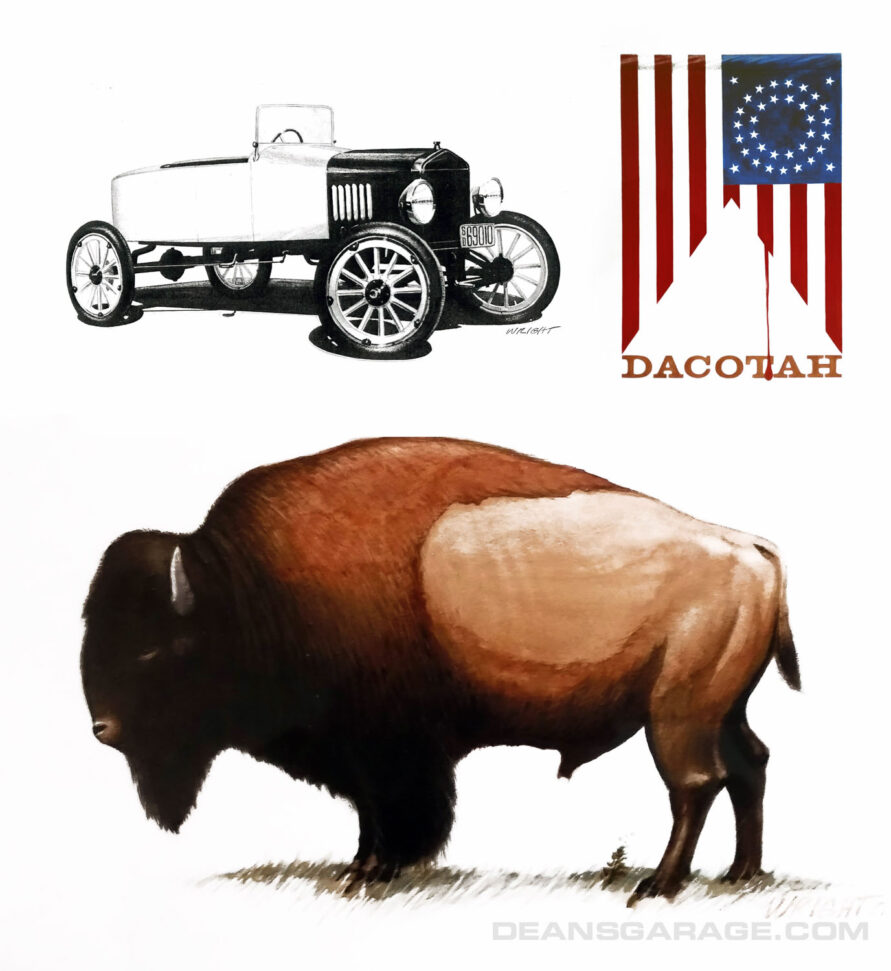

Dennis Shonsbye Wright (1932-2015) was born and raised with his six brothers and sisters on the farm of his parents George Richard (of English ancestry), and Helene Margrethe Shonsbye (Norwegian and German) in Rowena, South Dakota. This was and still is an agrarian community near the city of Sioux Falls. The land is notably known for the beautiful waterfalls of the Big Sioux River near its outlet into the Missouri. Over the years he became increasingly interested in the beautiful area in which he lived, and his art skills allowed him to represent scenes from that lost world in watercolor.

One single classroom housed all the children in school age of the community. Quiet and modest, always ready to help the others, Dennis was highly appreciated by all his school mates. This was to be a constant that accompanied him throughout his life.

His father George Richard built by hand and before the astonished eyes of his Dennis a very special Ford-T. He did so by adapting various parts from ‘T’ models from 1914 to 1917, which he finished off with a graceful boat-tail he shaped himself.

Dennis attended Washington High School in Sioux Falls. The bustle of the nearby Sioux City Air National Guard Base inflamed in him that inextinguishable passion for aeronautics so common among automotive stylists. The futuristic shapes of the F-86 Sabre, F-84 Thunderstreak, and the F-102 Delta Dagger excited him with the dream of becoming a fighter pilot. But fate took him in another direction.

Dennis used to hang around the city’s dealerships with his friends, excited by the heralded arrival of new models from GM, Ford, and Chrysler. Dealers at that time would soap the inside of their windows, hiding the new arrivals from curiosity until their public presentation. Not being able to wait that long, Dennis and the other boys would ‘intercept’ the trucks that brought the new cars in and follow them during their delivery run, to be the first in town to see them and be able to brag about their achievement.

Dennis attended South Dakota State College in 1954–1955. That was followed by military service in the Air Force which turned out very differently from what he had expected. He suffered an injury while playing baseball and became seriously ill. Confined to a bed, he was seeing his dreams frustrated just when he most intensely entertaining the idea of one day piloting the jets he was surrounded by.

After several surgeries, he remained confined to the beds of two other hospitals for long months of convalescence and transfers in which the doctors, knowing not how to diagnose his illness, tried to make him see that it was very likely that he would never walk again. In spite of this prognosis, Dennis worked every day until he was finally able to get out of bed on his own feet, and later practiced various sports to strengthen himself after his convalescence. However, several of the consequences of his unknown illness, or more likely the ineffective operations and treatments permanently affected him.

Dennis took advantage of the G. I. Bill which was a benefit provided by the U.S. Government at the end of World War II for ex-servicemen that provided low-interest loans to those wanting to pursue an education. Dennis was able attend the prestigious Art Center School (later renamed Art Center College of Design) in Los Angeles, California in 1957. His experiences growing up on a farm gave him the perspective to live simply. A scholarship helped pay for the tuition, so between that and the G.I. Bill he found himself in a position to be able to help his cash-strapped fellow students purchase required art materials. While at Art Center, Dennis became close friends with, among many other influential designers, the later futurist-artist Syd Mead.

In his first year at Art Center, Dennis married his long-time fiancée, Deanna Mae Cronk. Three children were born to the couple over the years: Craig (born in 1959), Shannon, and Patrick, the youngest, unfortunately born with serious health problems that made him the epicenter of the family’s attention until his death at age eighteen.

General Motors recruited designers by sending Design Staff representatives to Art Center at graduation. Dennis was not hired in the first round of interviews, but was encouraged to resubmit his work. After perfecting his portfolio over the summer back in Sioux Falls, he requested another interview. He was rewarded by a job offer at GM Styling at the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan. In September 1959 the family moved to Royal Oak in Michigan.

General Motors

In a manuscript intended to educate his children and grandchildren about his career, Dennis Wright wrote: “Never before or since in my life have I made a series of choices, all lucky ones, like the one that took me from being a farm boy to assistant chief designer designing automobiles for General Motors. Fascinating is the word that best sums up a thirty-seven year career as a member of GM Styling. I recall a famous quote from a fellow engineer who brilliantly described what constituted the GM Styling section within General Motors: ‘the only mental institution in the United States run by the patients themselves!’ This was an assertion of which, of course, all of us were completely proud.

“Professional development always on the cutting edge of technological progress, the continuous state if alert in pursuit of innovation, breathing an atmosphere of overflowing creativity, dilating the limits of the status quo: it certainly required an attitude, or if you will, a special insanity.”

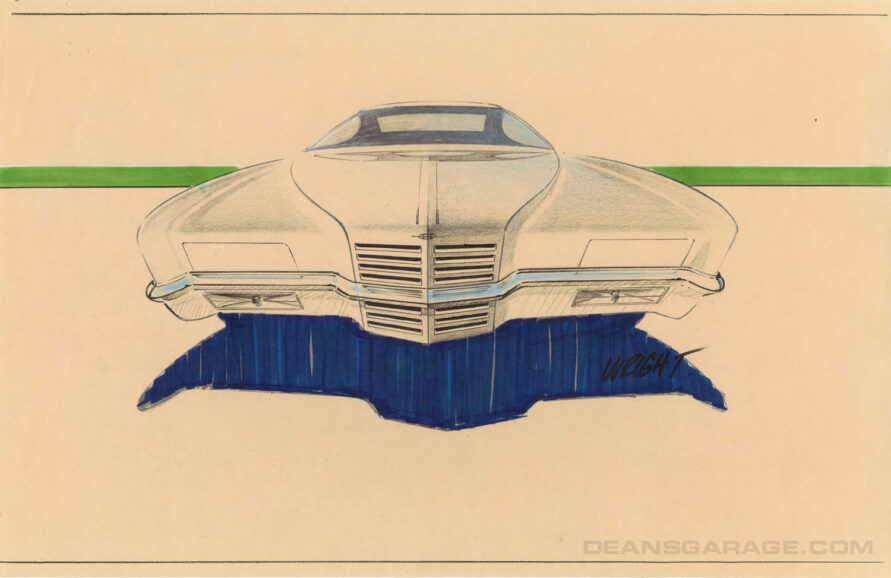

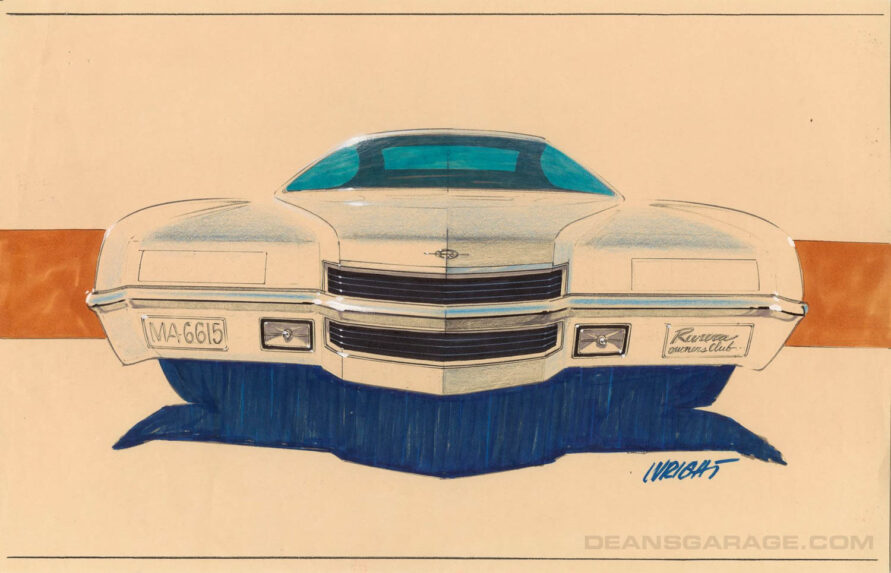

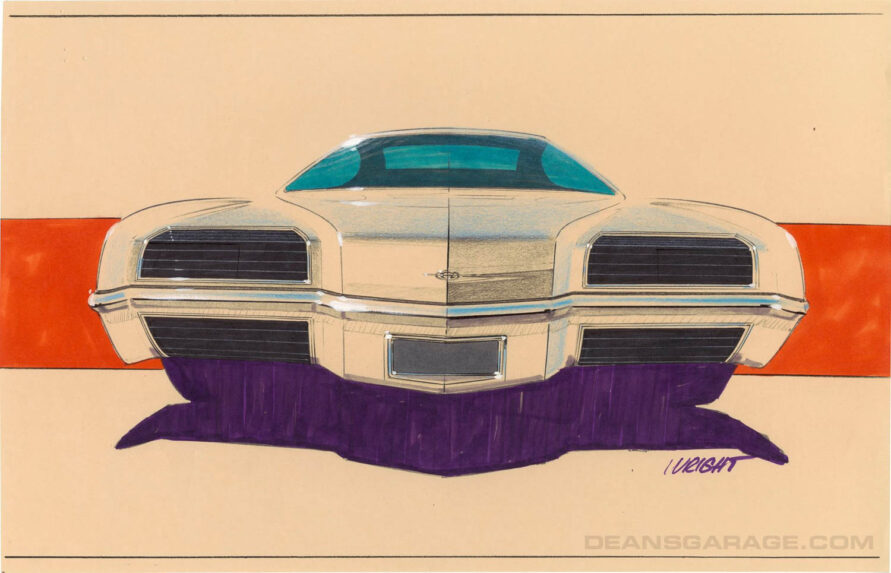

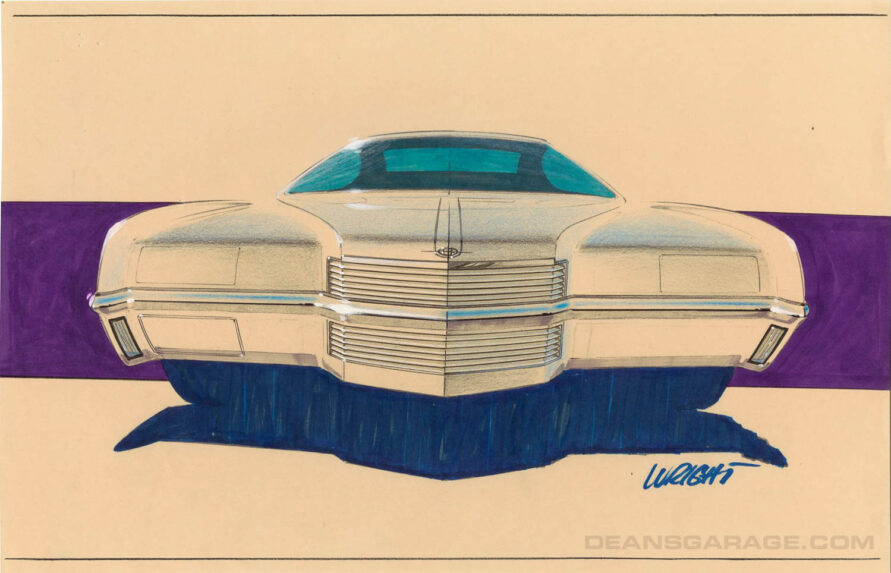

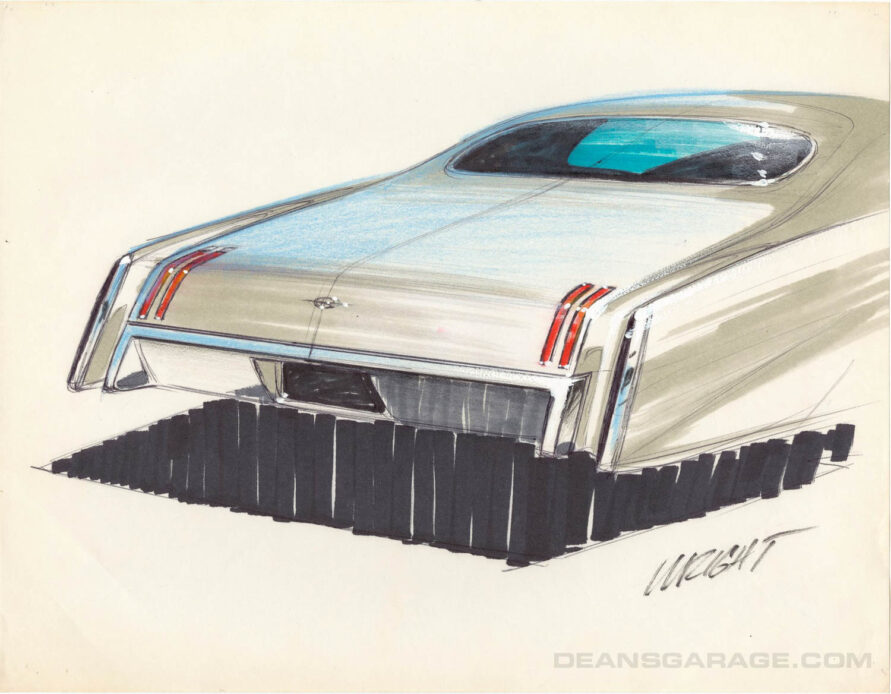

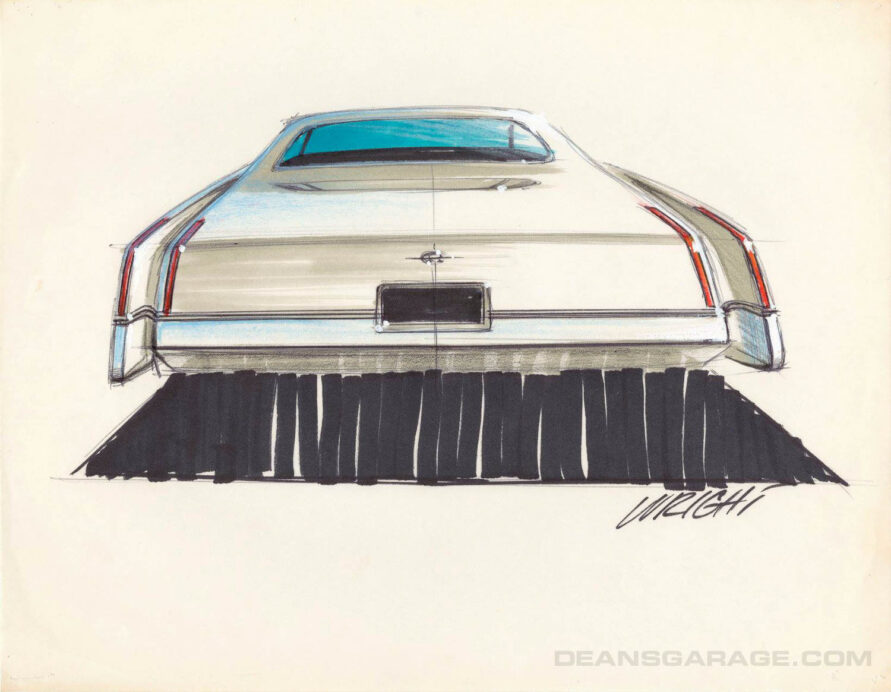

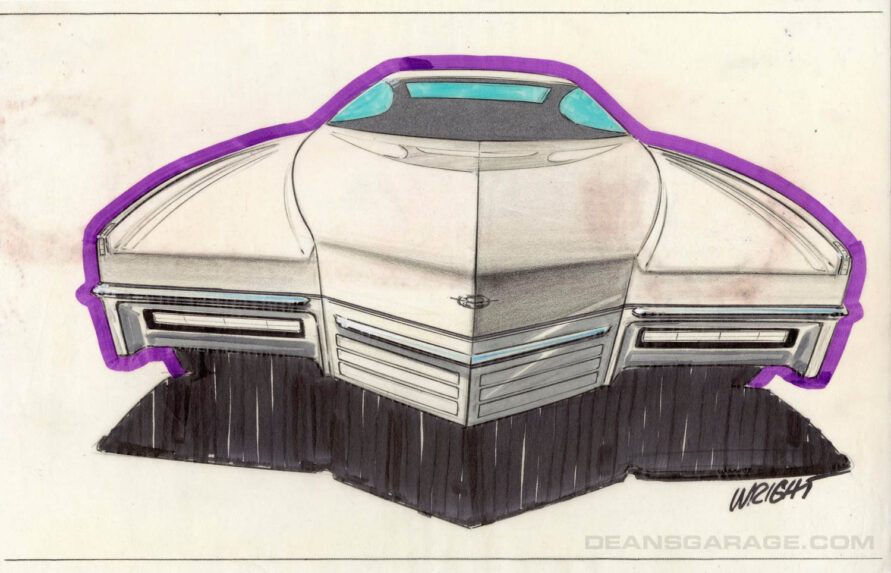

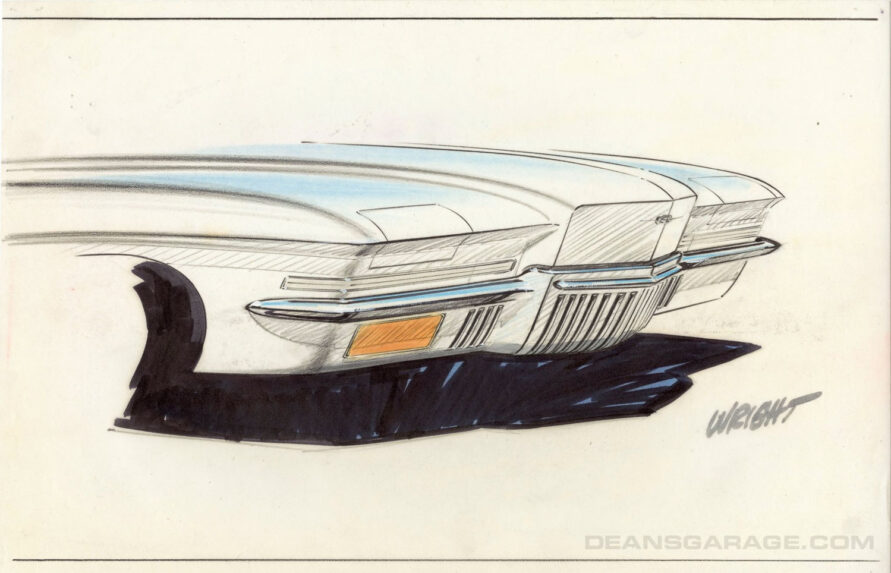

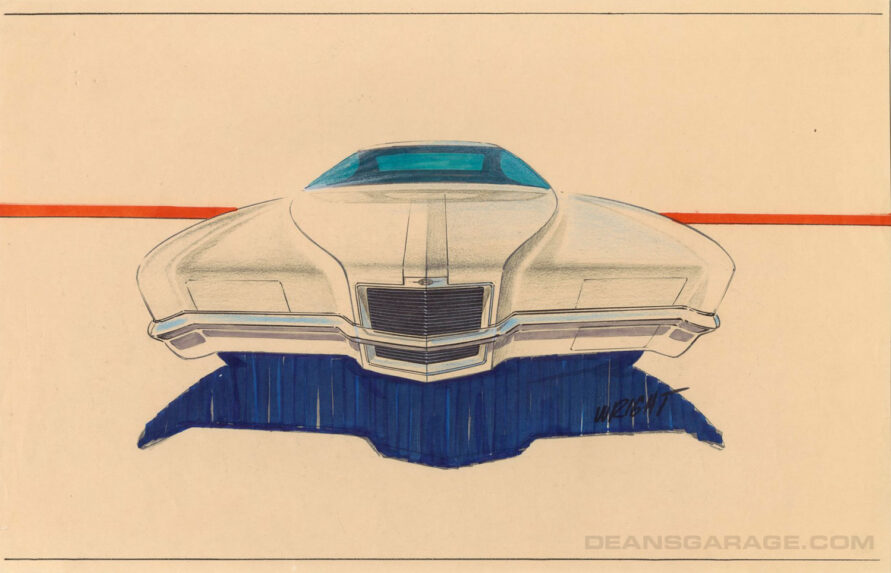

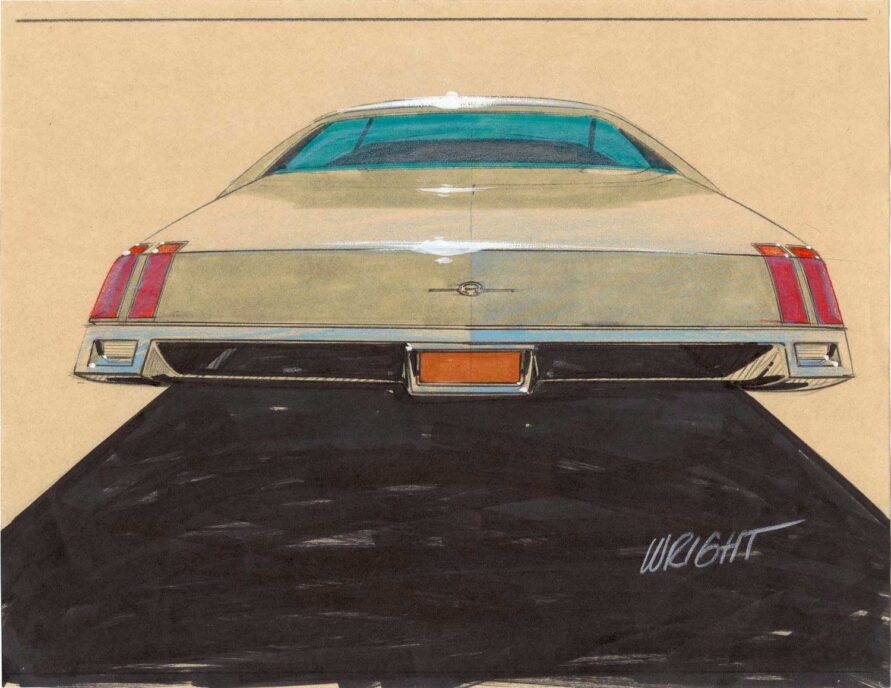

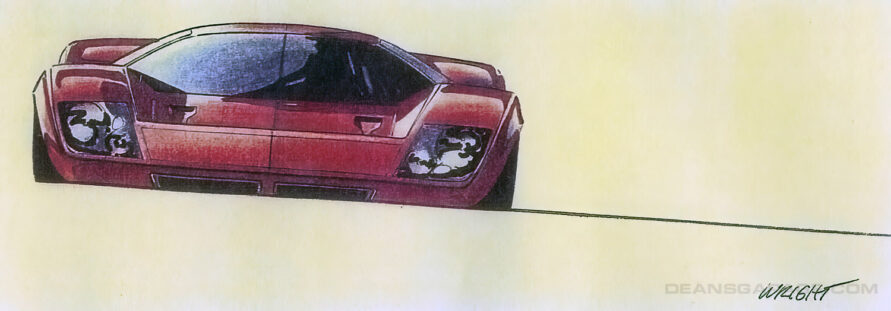

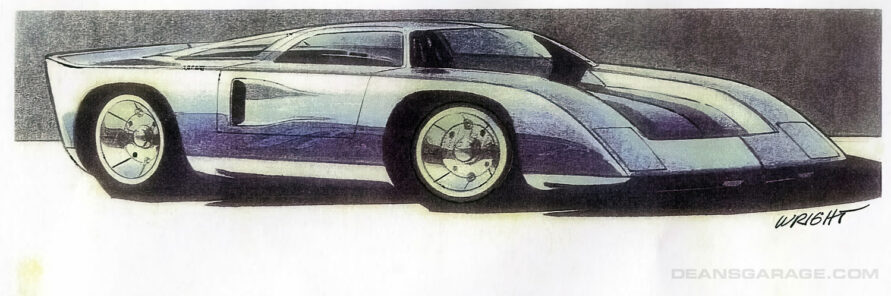

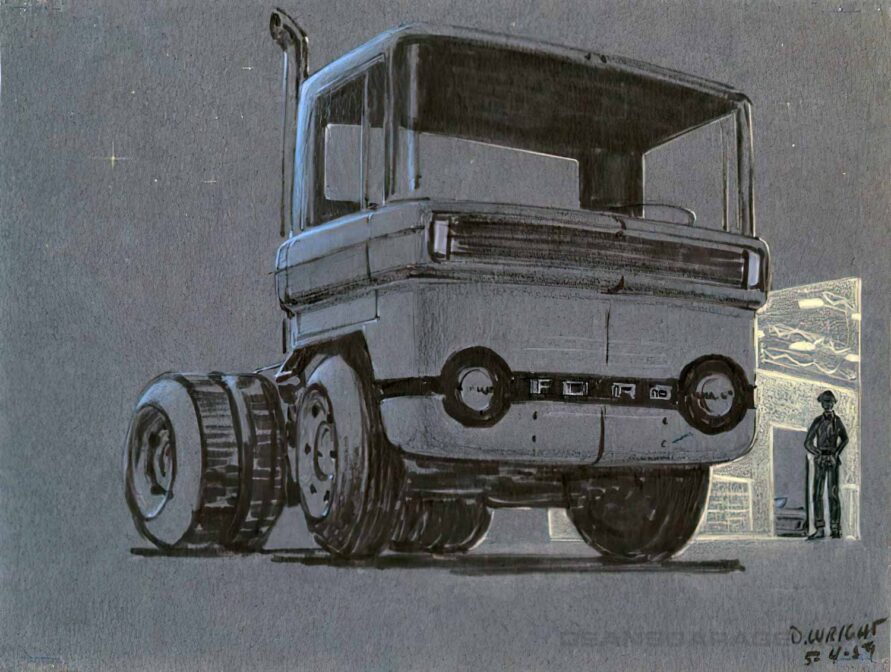

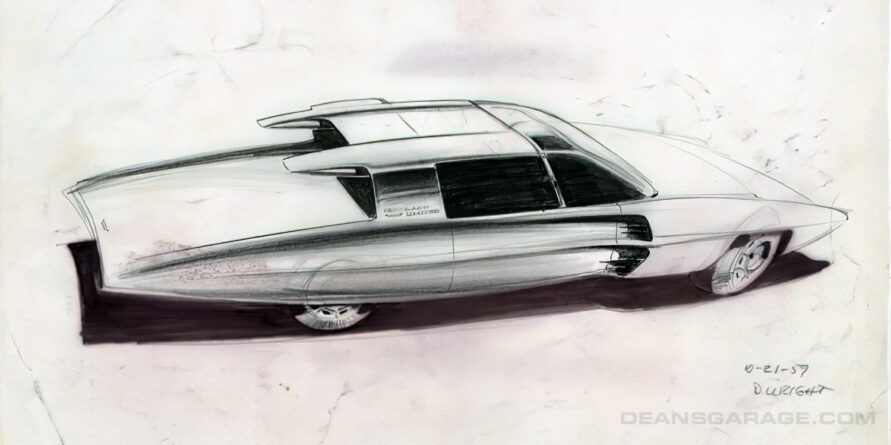

Wright then included multiple photographs and copies of sketches of his countless contributions, while reflecting: “Many ideas on paper trump over others simply because of the quality of their artistic execution or maybe only because of certain details that embellish them especially; these can be simple hubcaps with some distinctive feature, or perhaps a characteristic front grill. On other occasions it is a complete side view profile or a section, rather technical design of the proposed idea that wins the congratulations and pleases the taste of the managers. The concepts we developed in our advanced design studios were purely speculative, but they also had a major impact on the immediate product thanks to the special talents of the excellent VPs of design I worked for (Bill Mitchell, Irv Rybicki, and Chuck Jordan) that wisely intertwined them with the work of regular production studios.”

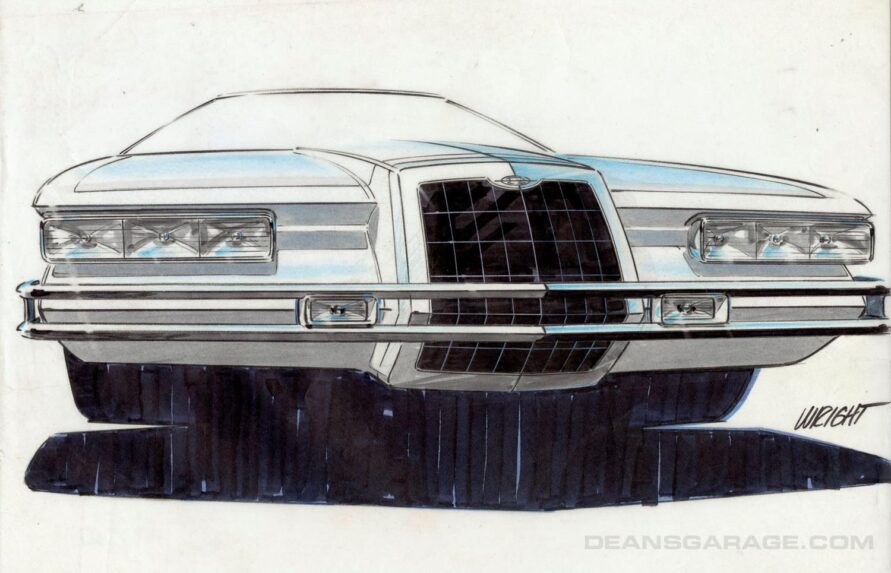

His involvement in the design of the Chevy II Nova 400, Sport Coupe, Station Wagon, and Convertible, as well as numerous details on the 1965 Buick Riviera are Dennis Wright’s most prominent contributions during his early years at GM, in which he was normally attached to Advanced I Studio led by the legendary Ned Nickels.

For Ed Glowacke, Mitchell’s second in command, in 1962 Dennis solo-developed a sensational Pontiac coupe which was ultimately canceled. It was in Advanced Studio III under the supervision of Bernie Smith that Wright became part of the team effort regarding the 1964–1965 New York’s World Fair design, the Runabout commuter concept car. He was subsequently transferred to Oldsmobile Studio to collaborate in the design of the memorable 1966 Toronado.

David R. North, former Oldsmobile Chief Designer: “Dennis was a wonderful person to collaborate with. We studied together at Art Center, graduating in 1959. From our class, which also included to the great Roger Hughet, only Syd Mead went to Ford. GM hired me in June, posting me to Pontiac Studio, though in my young heart I always longed for Cadillacs. In Pontiac Studio I was fortunate to work with Jack Humbert, Bill Porter, and Roger Hughet.

“Dennis didn’t give up when he wasn’t hired at first. He rebuilt his portfolio over the summer, traveled with it under his arm to Detroit afterwards, a strain on his resources, and got his job too! 1958 had been a bad year in auto sales. Brands saw the possibility of improving this by hiring new creative talent, which was good for us, and Harley Earl had just left the helm of what was then called GM Styling and is now GM Design. Bill Mitchell then held the position, revolutionizing the institution. That was the situation when we joined. For decades, Dennis was an important part of the groups responsible for some of the best GM cars of their time.”

Chaparral

Craig Wright (eldest son): “My father normally drew cars at home the most extravagant ideas that occurred to him. He would arrive from work and relieve my mother in the care of our younger brother, who suffered from serious health problems. My mother then could take a rest from the fatigues of the long day. Often, when he had the opportunity, my father would draw his most groundbreaking ideas during the small hours and the next day he would take them to the studio and would fix them on the wall surrounded by many others; he was curious to observe the reaction they might arouse.

“Some of his superiors, seeing them so disparate to the nature of the projects in progress, became annoyed by them; until they learned that he created these proposals in his free time. My father believed that certain ideas needed time to be accepted, and that is why he tried to introduce them that way, to show them visually, the sooner, the better. Several of them were actually considered and implemented some time later.”

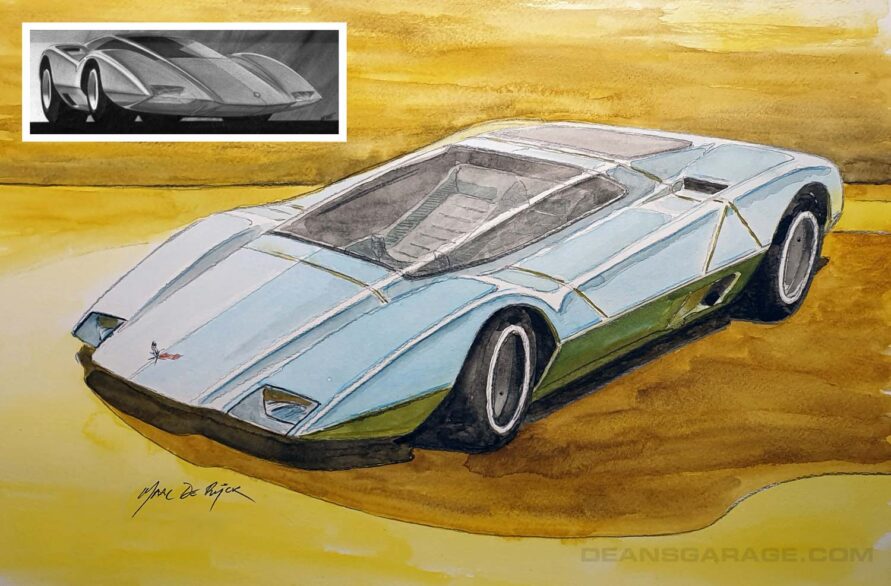

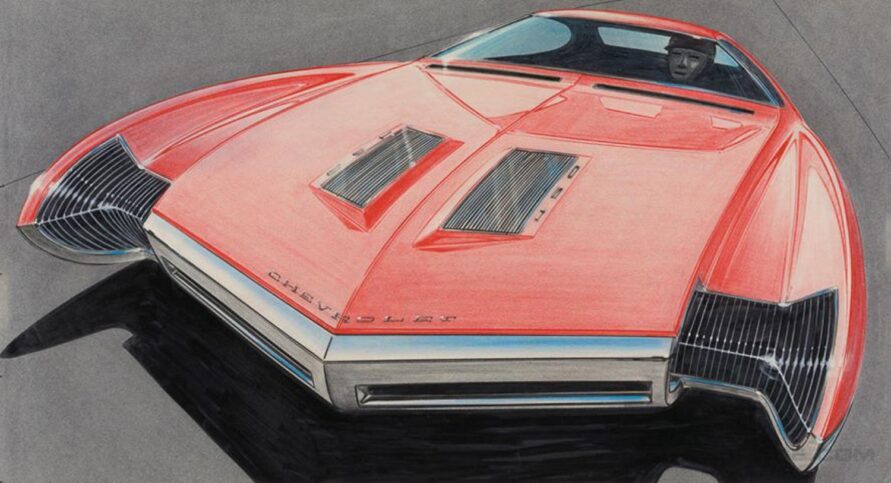

The original and innovative quality of these ideas had led Dennis (after the exhausting New York Fair program and the Olds Studio stint) to be assigned to Chevy III Studio directed by Larry Shinoda (Mitchell’s right-hand man for many truly exciting car projects within GM). Chevy III Studio acted as an independent laboratory, free from the interference of managers and committees and at the sole service of Mitchell.

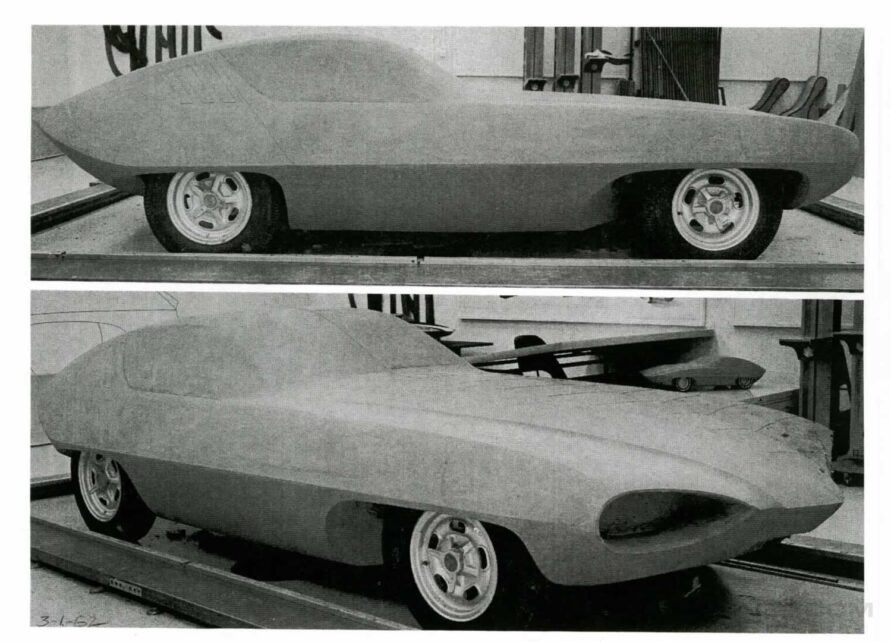

There was a secret studio in the warehouse located across 12-Mile Road, across the street from the GM Tech Center. This was a most discreet place where several exotic Chevrolet projects were born, as well as some of the group’s concept cars, including future Corvairs and Corvettes. The Warehouse Studio also served as the ultra-secret location for the development of concepts related to Jim Hall’s Chaparrals. Dennis joins forces here with both super-talented designers John Schinella and Allen Young—the three of them helped and supervised by Shinoda. The 1965 Corvair, the 1966 Impala Super Sport 396 Coupe, the 1967 Impala Sport Coupe, the final version of the Astro I were born during Dennis tenure at Shinoda’s secret garden. What’s more, the studio’s Corvette C3 proposal won over Corvette Studio’s efforts led by Hank Hega.

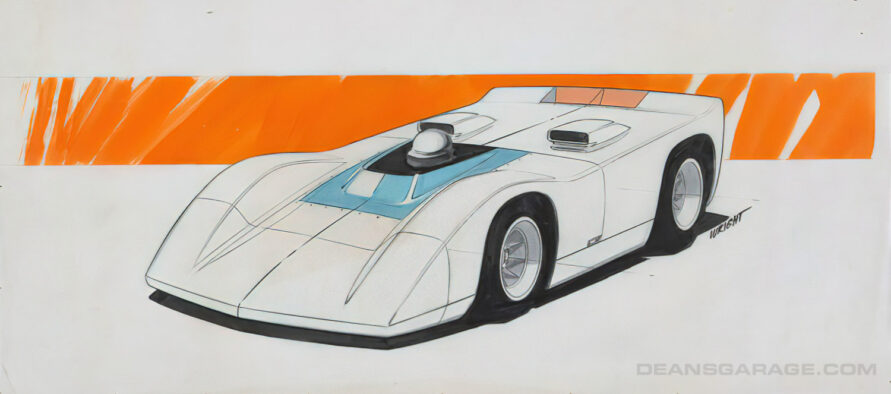

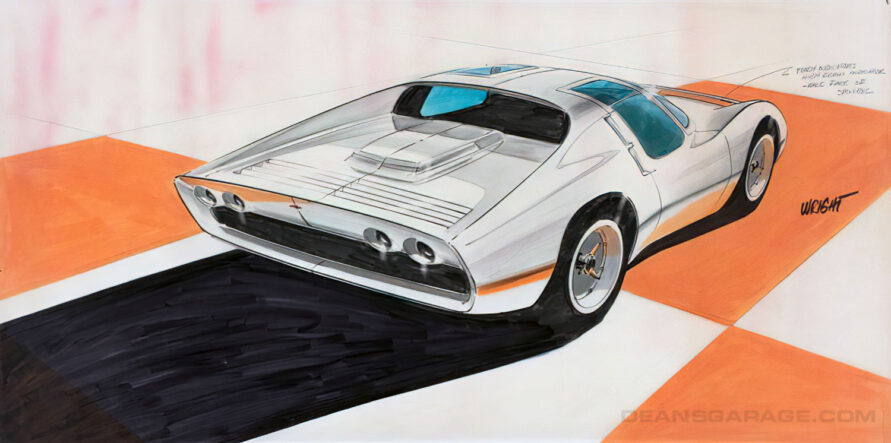

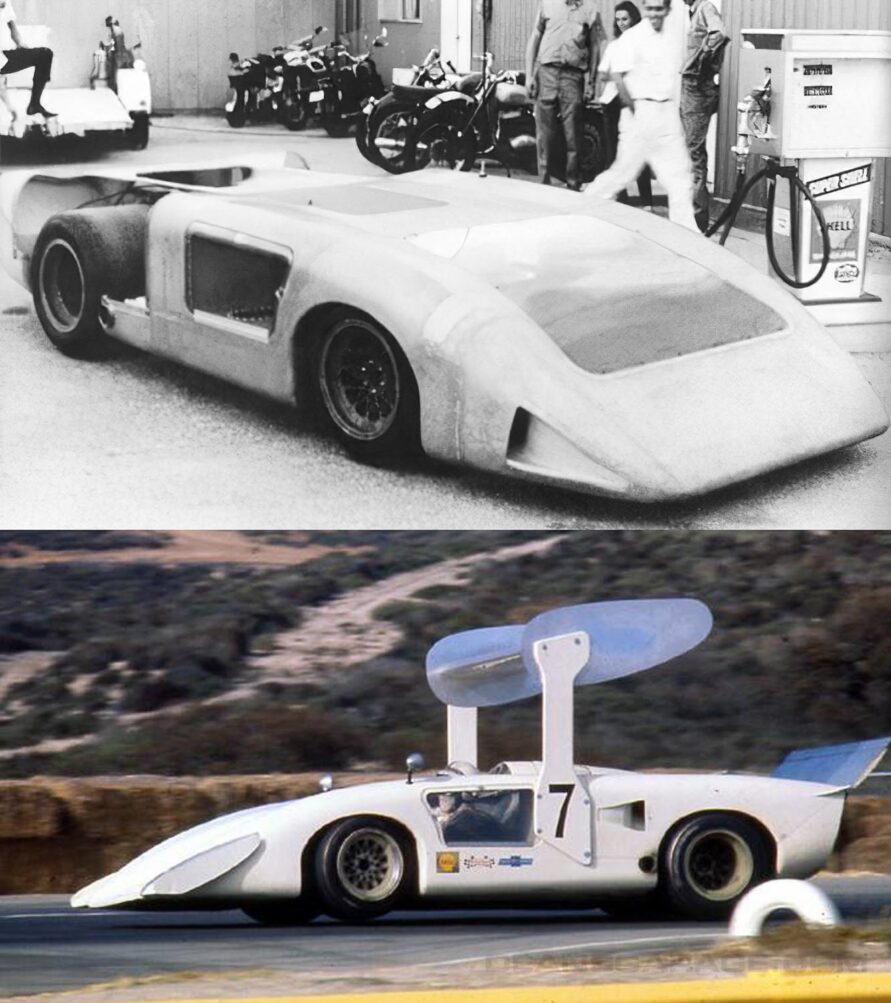

Roy Lonberger: “I remember Dennis Wright very well. We were mates at Chevy II Studio in charge of Camaros and Corvettes. That was around 1967–1968 and just as I participated earlier in the Chaparral 2D project, he did the same in the wedge-shaped 2H project. It is very likely that he previously participated in the design of the GS-II (that influenced the Chaparral 2E), responding to Bob Larson and, above him, Larry Shinoda. Dennis was temporarily transferred to Chaparral in Midland, Texas, to work on the 2H project and follow tests of the car at Chaparral’s private race track, Rattlesnake Raceway. As the name indicates, rattlesnakes abounded and it was not a good idea to get out of the car away from the offices.

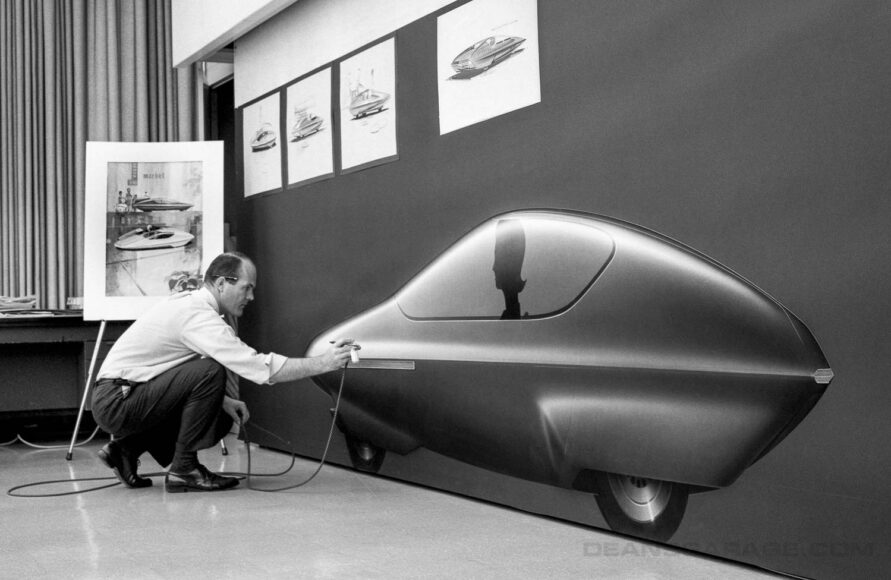

“I never really got close to him. In the studio he was often silent, engrossed in his work, either creating incredible sketches on the drawing board or creating fabulous full-scale renderings with the airbrush, which he handled with great mastery.”

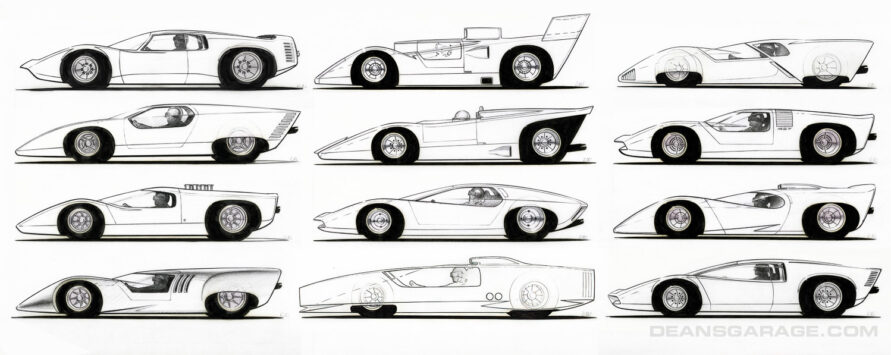

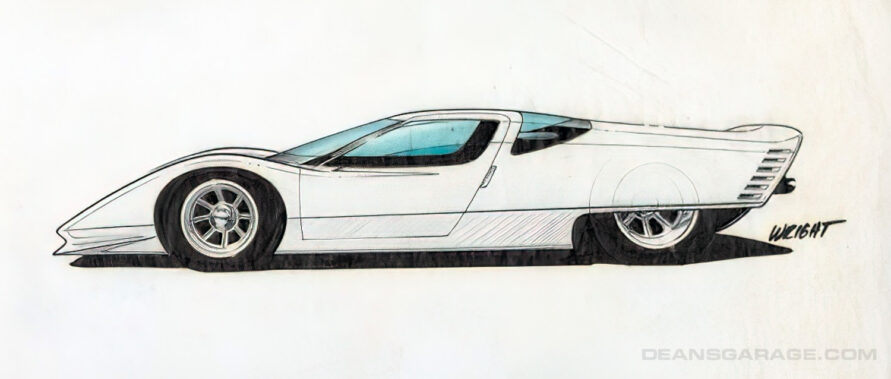

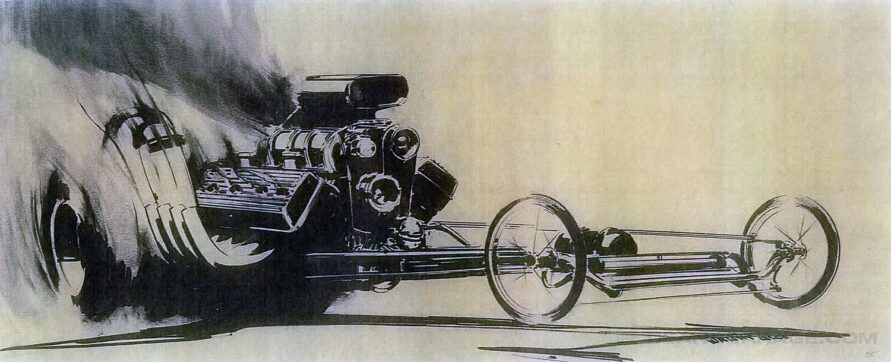

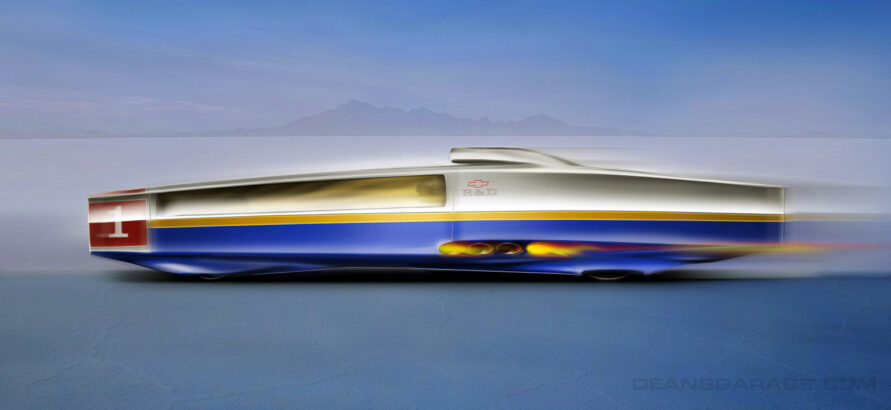

It is to this period of Dennis Wright as a member of the clandestine Chevy III Studio that the majority of the uncompromising sports car illustrations in this article belong. These speak for themselves not only about his fertile imagination, special talent for sports car design, but also of his deep involvement in race car and show car projects. GM always maintained absolute silence about the support and close collaboration of Styling and Chevy R&D departments with Chaparral, and in a probable but never materialized Chaparral street sports car. Because of the secretive nature of this work, Wright never boasted or even mentioned at home having been part of the legendary history of the revolutionary Chaparral saga of the 1960s.

The Chaparral were very advanced technically for their time. Most models were built on a never-before-seen composite monocoque (integral with the bodywork and oven-cured on the 2H), equipped with a semi-automatic gearbox mechanism, active aerodynamics and suspensions (the latter particularly on the 2H), computerized telemetry, and a myriad of cutting-edge technologies that still fascinate and intrigue us more than half a century later.

Ed Welburn on Dennis Wright and Chaparral:

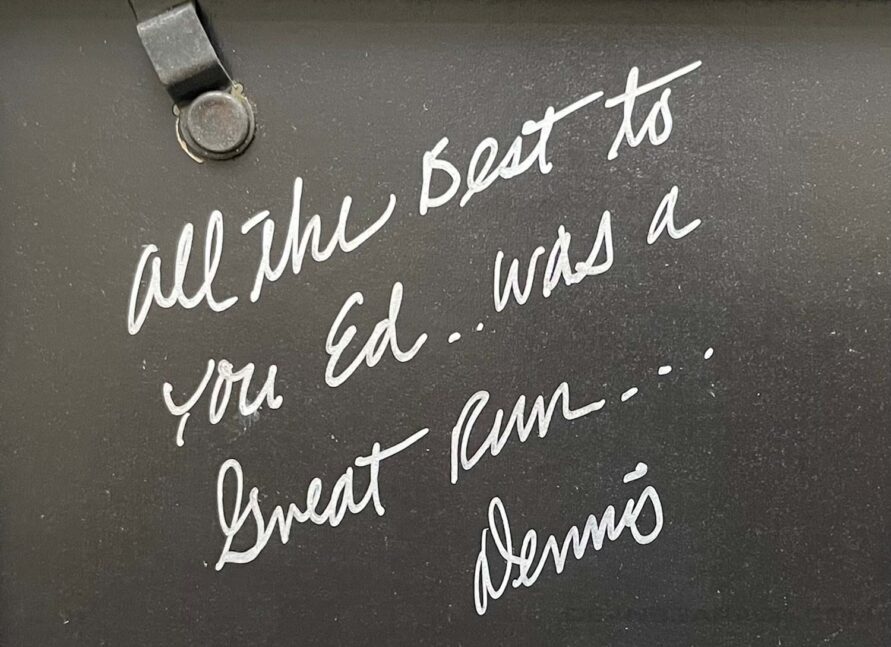

“I spent many of my formative years in the Oldsmobile exterior design studio. Most of that time was in Olds 2, the studio responsible for all things Cutlass. When I was named chief designer of Olds 2, Dennis Wright was named my assistant chief designer. Dennis was the perfect choice. He was a rock. He was incredibly honest, strong, creative, and a great mentor to the younger designers in the studio. I might add that I also learned a lot from Dennis. Because of his many years of experience, no engineer could fool him. In fact engineers learned to respect him and actually learned from him. Dennis and I worked together on the Cutlass Supreme, Cutlass Ciera, and the Antares concept car.

“Even though Dennis knew that I was a fan of Chaparral he rarely talked of his involvement in the project many years beforehand. That said, even though it had been years since he worked on the design of Chaparrals he often developed small sketches of race cars much like the Chaparral 2H, with a sleek profile and windows on the side. Years later, when I had developed a great friendship with Jim Hall, I told him that many designers were inspired by the 2H. In fact, within a year of its introduction both Bertone and Pininfarina had developed concept cars with a similar profile and window configuration. Coincidence? Maybe, or call it inspiration from Dennis Wright’s sketches. In recent years I have developed a great friendship with Jim Hall and I had the opportunity to drive multiple Chaparrals. Driving 2H was my desire and the greatest thrill.

“When our glorious time working together came to an end, Dennis gave me a signed and framed sketch, with a very special note on the back. It’s been many years since he gave me that sketch, but it remains on a shelf in my home as a special memory of a special time and a special person. Thank you, Dennis.”

Overseas, Buick, Oldsmobile Studios

Dick Ruzzin, GM Europe Styling Director from 1991 to 1996 and later Chevrolet’s Design Director, takes the had this to say about Dennis Wright: “The Overseas Studio within GM Styling at Warren proposed designs for programs being carried out at the GM divisions in England, Germany, and Australia. At the same time I was following these closely, I also made suggestions along the way. It was in this studio that I met Dennis towards the end of the sixties. The studio was also in charge of the development of the small cars of the group, so I would say that we, Dennis and I, first worked together on a vehicle the size of the Fiat 850.

We often worked together several times in the following decades. I was at the time Assistant Chief Designer for Ned Nickels, the author of numerous Buicks in the 1950s. It was certainly a pleasure to work with Dennis, a highly imaginative and capable, creative man. At least a couple of years had passed since we first met that he first showed me some of the exciting sports car designs that he had created in Larry Shinoda’s studio. These included also a number of racing car designs. He told me the story of the removable rims that he developed for Chaparral and that Mitchell immediately wanted for himself at the very moment he saw them, so Dennis had to reinvent them in the form of false spoked rims, thus creating a school that dozens of rim manufacturers followed (such as BBS).

“He talked about it all with great shyness and modesty, natural qualities of his, although it seemed to me that he deeply longed for that period and wished he could go back to those days with Shinoda. Dennis was an exemplary worker with a great understanding of the profession and the environment. As a human being he was exceptional, very reserved (we never knew anything about his private life), only the basics about his origin and his studies. He was always available to help others and he never waited to be asked for help. He was amazing at doing full-scale renderings with the airbrush. I was terribly bad at this and he taught me how to do it expertly. I don’t remember that he had close friends among his colleagues, but instead everyone without exception liked him. Although there were many more, I particularly remember several projects we worked on together. For example, the Opel 1900—a two-seater on the Vega platform, predecessors of the GMX programs and front-wheel drive vehicles.”

During his career at GM, Dennis was involved in many projects, including the mid-1970s Firebird, the 1969 Oldsmobile GT XP-888, the 1980 Chevrolet Caprice/Impala, the 1981 Chevy Citation X-11, and the 1981 Chevrolet Monte Carlo. He worked on the Toronado (whose aerodynamics he helped to refine to achieve an excellent final Cd of 0.345), the 2- and 4-door 1987 Delta 88, the Cutlass, and the 1992 Cutlass Ciera. He worked on the 1988 Buick Reatta, the 1993 Regal, the Somerset Regal, the Skylark, and the Roadmaster (and its Station Wagon variant), and the Oldsmobile Antares from 1994 (that led to the 1998 Intrigue).

Wind Tunnel

Craig Wright: “My father was passionate about aeronautics. He used to take me with him to air shows, while my sister Shannon would accompany him to the auto shows. He didn’t know the science behind aerodynamics, which interested him so much. He used to say that many equated this science with an ‘esoteric’ discipline. However, he was able to visualize the flow of the wind around the car and deduce the corrections that a certain shape needed. I was particularly fascinated by this facet of him, and often he was particularly motivated to improve this feature in the models he worked with.

“For some time I studied aerospace engineering and was therefore able to talk to my father about aerodynamics. I knew the science behind it and he, with his intuition and experience, knew the effects produced in the wind by the encounter with the form of a car, and the way to take advantage of it. He listened carefully to the engineers in the field and then shared with them his own ideas. These often, in the first instance, belittled the indications coming of him, considering him merely ‘an artist’. He then asked to stay in the wind tunnel when the engineers went home to check that his intuition was not wrong, prove the validity of his ideas and refine them. Thus, he achieved great appreciation from these same engineers, with whom he collaborated intensively for years, first in a wind tunnel in Ottawa, Canada, then at the Lockheed facility in Atlanta, Georgia, and finally in the new General Motors tunnel built at Warren’s own Tech Center, which opened in 1980—the first full-scale automotive wind-tunnel in the United States.”

Some Anecdotes and Conclusion

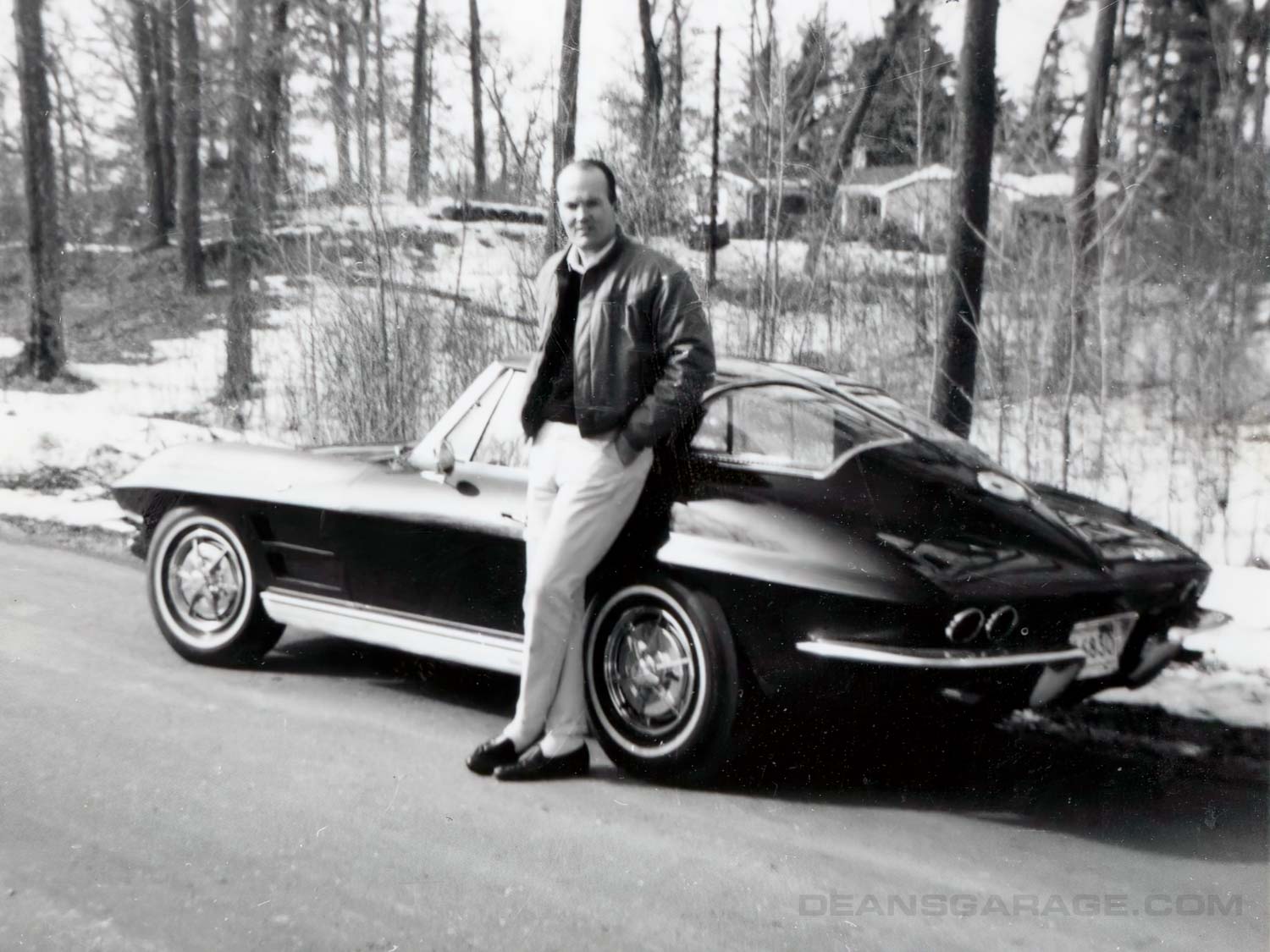

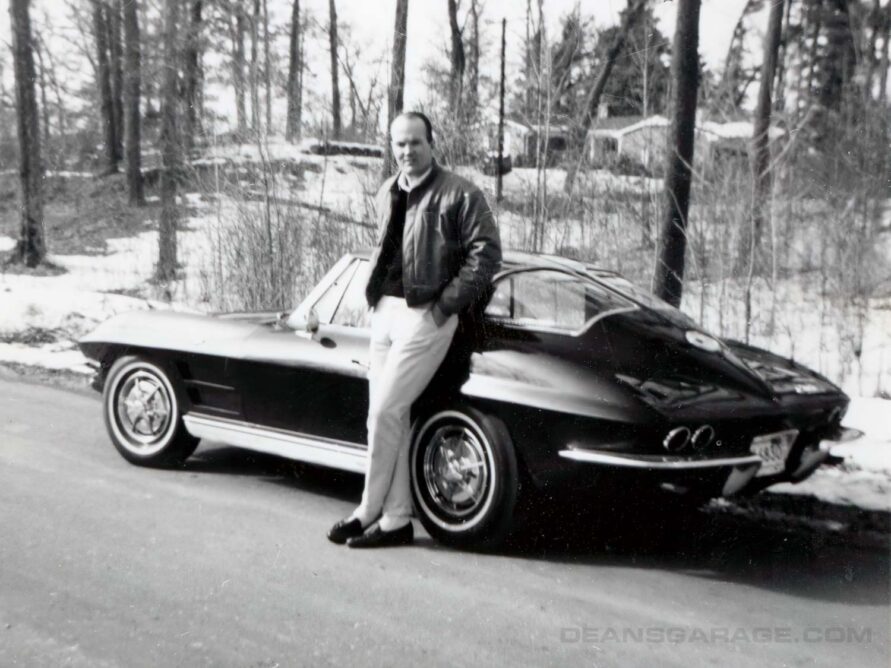

Craig Wright: “Under a vehicle renewal plan for GM employees, my father could drive a new car from the group every quarter, with the obligation to purchase one of them annually, being allowed to sell it within a year of purchase. Through this formula, I remember we had a Trans Am by the time I could already drive, so I enjoyed it for a whole year. We also had models from Corvair and others. My father was particularly taken with a black ‘Split Window’ Corvette Sting Ray that he got when I was four years old. He made a special chair so that I could travel safely in it, but he had to sell the Corvette when my sister was born in order to buy a bigger house, the one in which we grew up, although he also later drove another 1966 Corvette and a 442 from 1969, which he just adored.

“My father spoke little about work at home and I only vaguely remember allusions to Larry Shinoda. I recall better how much he admired Bill Mitchell, he said, for his constant effort to explore new avenues in car design. My father was convinced that after Mitchell’s retirement this spirit declined somewhat at GM. Despite his introverted and modest character, my father was a really sociable person who got along with everyone and was interested in their stories. He got along great with the modelers, something not as normal in the profession as one would think. He knew the cleaning staff each one by his or her name, and used to sensitively share with us the personal experiences he gathered from them.

“Once retired, he flatly refused to move to a grandparents’ neighborhood at my mother’s suggestion, as she would have wanted. He loved being surrounded by the young people, that always helped him feel motivated and optimistic. He really enjoyed giving talks in schools and he especially enjoyed the occasions when a girl proved to be better than the boys in class at drawing cars. I also went with him many times to see my uncle Jack, his brother, who used to race a car in South Dakota. My dad liked jazz, but my mother hated it, and so he had a good collection of records that were new, as he didn’t almost play them. Much stronger was his passion for certain periods of U.S. history. I visited with him several significant sites of our Civil War, such as Antietam or Gettysburg. He abhorred the massacre committed against the indigenous populations and most of the thousands of books that he had at home, beyond the many that he had on art, aviation and history, especially the military, dealt with these topics.”

George Camp, colleague and friend, designer at the GM Truck Studio, Chevy Studio and others: “Never throughout my career have I had the opportunity to work on the same project or be in the same studio with my friend Dennis Wright. However, we lived only a couple of blocks apart and often socialized with our wives. Once we retired we would meet up every Monday morning at the same restaurant to reminisce about our days at GM or talk about topics we loved, the new cars, old cars, Italian coach builders or WWII planes.

“Dennis started his career at GM about four years before I did, so at first I saw him as the veteran I could learn a lot from. Dennis was the perfect fit for the archetype of a Car Guy. Only his family was more important to him than cars, his great passion, with an inveterate predilection for Oldsmobile. In fact, later in his career, he was Assistant Chief Designer of Oldsmobile Studio I, that is, the right arm of Ed Welburn, who from 2003 to 2016 was also GM’s Vice President of Global Design, the most important position possible in our profession.

“Dennis, as the culmination of his career, was instrumental in the materialization of the Oldsmobile Intrigue sedan, among several others. He too was proud, with all fairness, of his time spent with Larry Shinoda and spent in developing Corvettes. By then, Chevrolet was deeply but unofficially involved in motorsports, collaborating closely with the likes of Penske, Jim Hall, Smokey Yunick and several others, and Shinoda’s studio was pursuing these projects, Dennis being an active designer there. Dennis was enamored of all possible racing Chevys, especially the Sting Ray, Scarab, Chaparral, as well as the loud, wacky dragsters!

“The quality that I personally valued most in him was his integrity. Dennis was a man of unimpeachable honesty, who could be truly trusted, as well as the highly respected professional in our business that he himself was.”

Dennis Wright, retired from GM in 1996, and died on October 12, 2015 in Jackson, Michigan at the age of 83.

Thanks to Christo Datini, Larry Kinsel, and Wayne Morrical of the GM; Craig and Shannon Wright; George Camp, Roy Lonberger, David North, Ed Welburn, and Dick Ruzzin.

Edited by Gary Smith

From the Dean’s Garage Book.

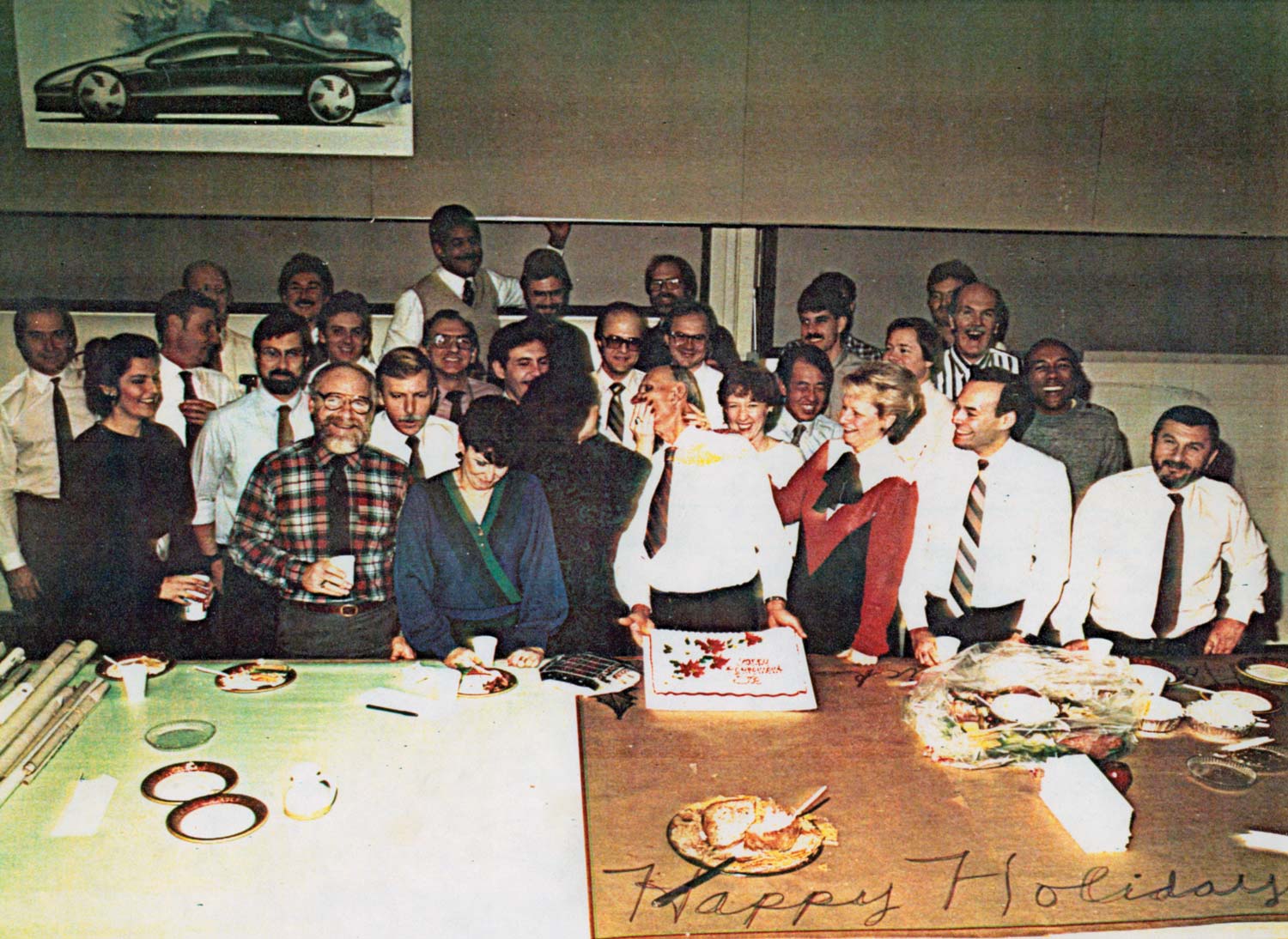

Dennis Wright is on the right in the striped shirt.

Joe the sweeper’s retirement studio lunch. Recognized in the shot (roughly left to right) are Bob Cordero, Steve Pasteiner, John Bloyer, Mark Kidd, Mike Filan, Andrew Link, Mario Angelini, Rick Zabor, Ed Krantz, Pete Han, Tom Peloquin, Carol Perelli, George Prentice, Dennis Wright, Dave Rand, Jim Perpina, and George Kozak. Taken in Buick Two Studio. Used with permission.

Dennis and I had a couple of background similarities, I grew up on a farm and so did he. I do remember the Toronado that we worked on while in Ned Nichols studio. That was the second Bill Mitchell Toronado, a challenge to the 1969 version that had been going on in Oldsmobile Studio. It was based on an earlier BILL Mitchell concept, a four passenger Indianapolis car, for the street. We took that design and developed it over the platform that was being used at that time. I think that car still today, if it pulled up alongside you would shock you. It was quite unique.

Ned Nichols really liked Dennis and we did a lot of great work in that studio. A very admirable person, Dennis was a great man.

A very important point that I missed in the comment above is this. The work that was done at Chaparral with collaboration from the Larry Shinoda studio, and Dennis being a great part of that, literally changed racing around the world, forever. The wings and ground effects have evolved to what we see today in Grand Prix cars. That groundbreaking work was done by a few people, Dennis Wright was one of them.

And the little 856, based on the Vega platform. Oldsmobile wanted that car so badly but CHEVROLET was not about to allow anyone to build a low cost sports car they could appeal to many more in the market than the CORVETTE. The 856 was followed by another Oldsmobile attempt, that we designed in Overseas Studio. a coupe that was developed from the Vega platform.

A beautiful sporty coupe, it would have been a terrific product for Oldsmobile, except that the engine in the Vega was to become a traumatic failure. If the engine in the Vega had not failed it was very likely that Oldsmobile would have happened. It was a beautiful four passenger coupe that looked a lot like the BITTER CD. That was done after we we found out that the Oldsmobile had been canceled.

Many thanks Gary for the editing and publication; and to David Rodriguez (from Spain) for the excellent article. I think that he captured Dennis perfectly.

Roy

Dennis was my supervisor in the Olds 1 Studio. He was such a low keyed powerhouse talent. Nothing ever rattled him and you could always count on Dennis to have your back.

As Ed Welburn said, Dennis was indeed a Rock. He was someone that I admired and had great respect for.

Excellent write up about a fellow designer that I never worked in a studio with, but did interact with on many occasions. This article explains what I recall feeling but never was conscious of through all those years – why he was referred to as the “rock” by those who had spent considerable time working with him. Very spot on descriptor of this quiet, solid man of high integrity who just happened to be a designer…

I love the collection of designs. The value of simple side view ideas is clearly exposed. Impressive.

Great work Gary.

Very nice article about ohne of the best designers of all time. Chevys secret racing program (i have read Mr. Van Valkenburgs book) is one of the greatest highlights of GM. Like everything GM did at the time, it was perfect. The perfect and best secret racing program that EVER existed!

Now I have a simple question as a fan not as a professional.

The things that GM has created – the cars from the 1930s until today – the V16 engine design. The 1940s US Army trucks. The 1957 Eldo. The backlights of 1967 Camaro. The Chevy Vega Cosworth. The Buick GNX. The Chevy Beretta. The C8 Corvette. The Cadillac Lyriq. And so on and on! I’m reading your fantastic site since the Tony Rehling Packard article.

Why have all this products a soul? And most new things have not? I’m sure for you (the GM designers, who created all this fantastic products) you have a simple answer. May be your answer would be of some help in a very difficult time!