1958-60 Lincolns—What Went Wrong?

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

For those who believe 1958–60 Lincolns were beautiful and well built, but misunderstood, this article may not be for you.

Nineteen-fifty-eight was supposed to be the year Lincoln caught and surpassed Cadillac in sales. Ford Motor Co. spent a lot of money in the belief that would happen, and there are many responsible for the failure of 1958–60 Lincolns to sell up to expectations. Although some at Ford didn’t know it yet, in 1958, they were also in the midst of the Edsel disaster—and Lincoln was a part of it.

In fall 1956 Ben Smith replaced James Nance as head of Lincoln Division, which was soon to become Lincoln-Edsel-Mercury, and then Lincoln-Mercury Division. For the disaster, it’s easy to blame Smith, who took over as head of Lincoln and John Najjar, Lincoln’s chief designer who Smith inherited, but that’s probably unfair. In 1961 Smith was the one who finally made Lincoln profitable and saved it from being discontinued. And Najjar, who had been a Ford designer since 1938, recovered after being dismissed as Lincoln’s chief designer and continued with an otherwise stellar career as a Ford designer until his retirement in January 1980.

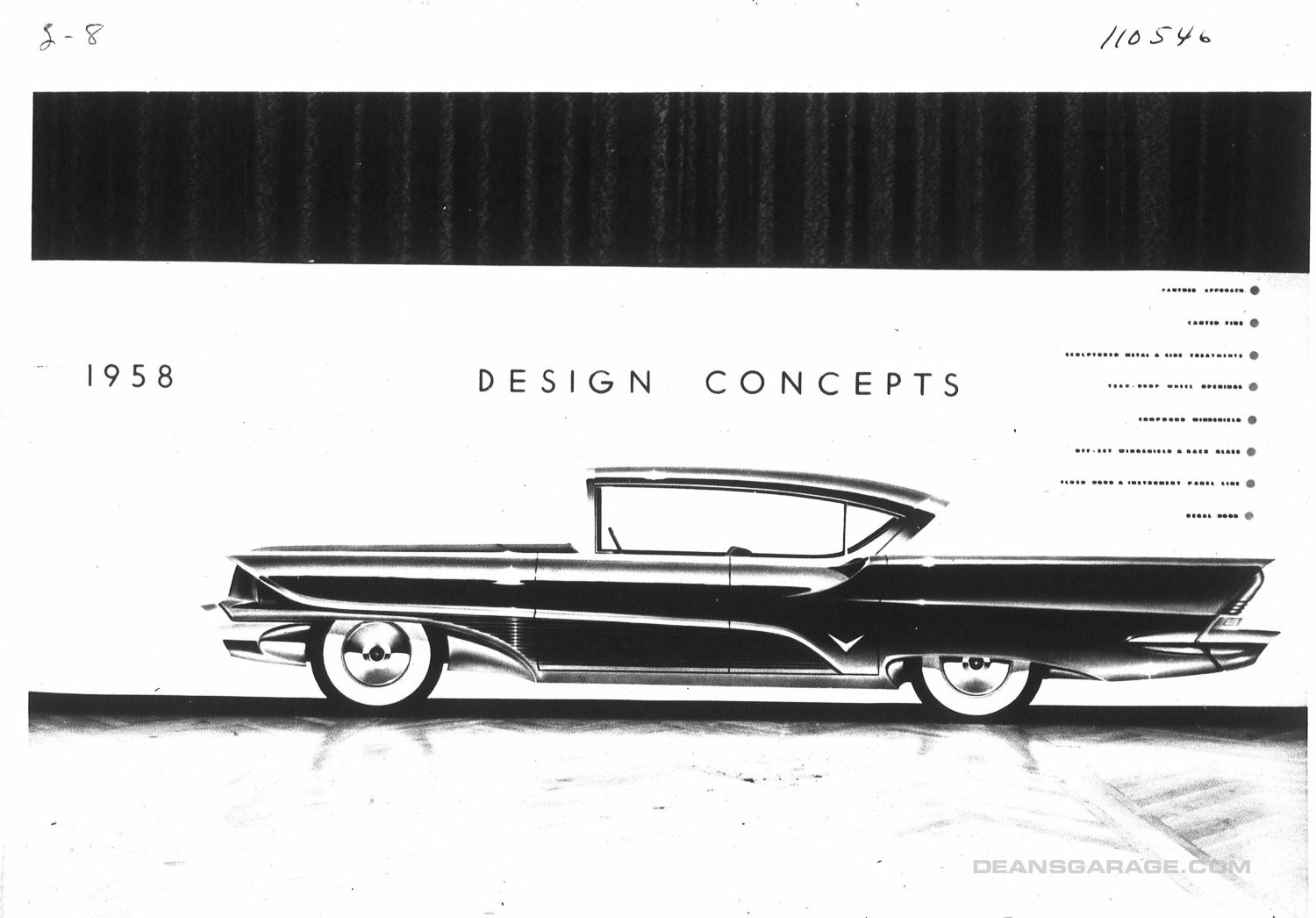

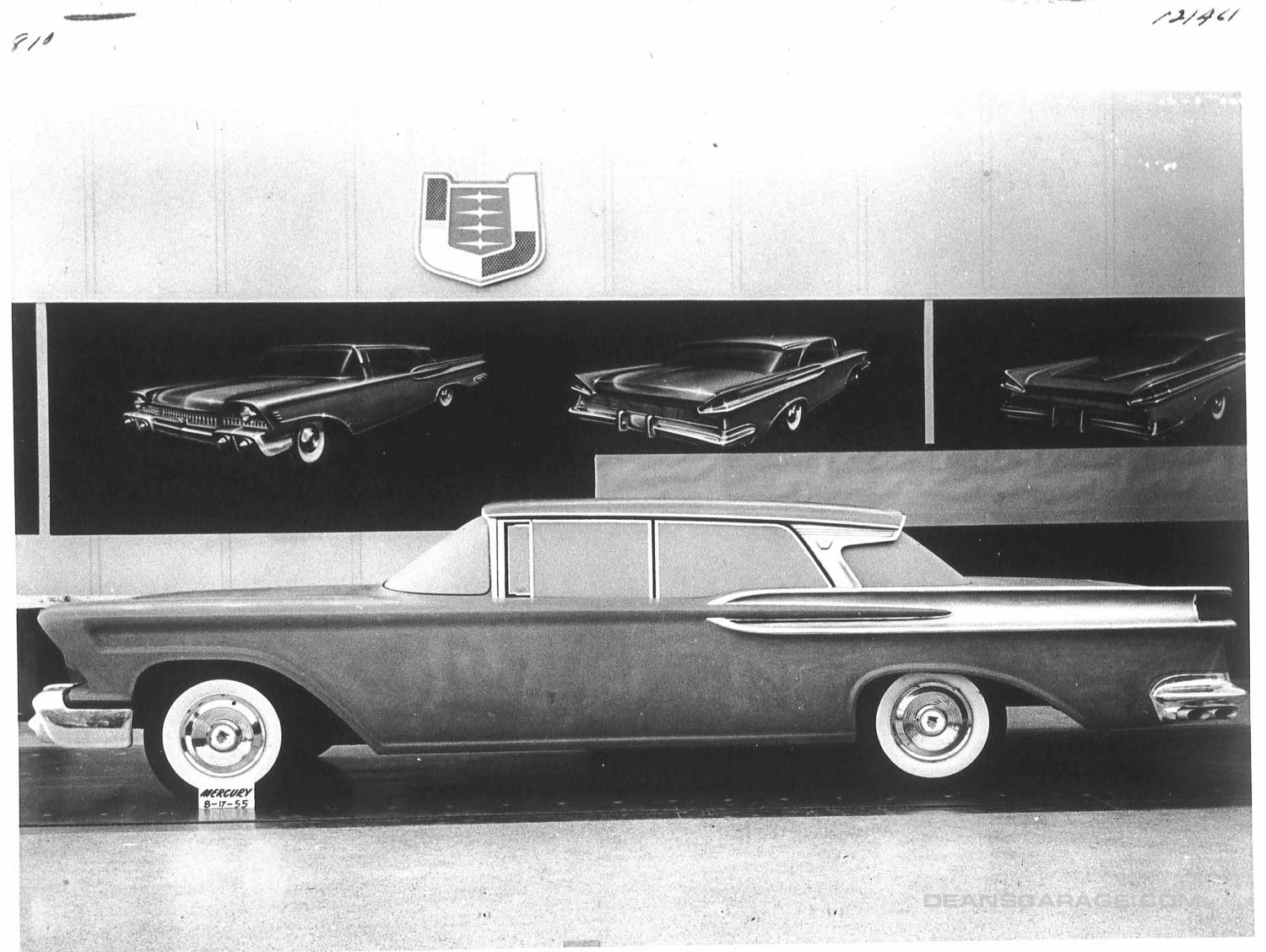

In May 1955 when George Walker took over as head of Ford’s Styling Department, he and his assistant manager, Elwood Engel, chose Najjar to lead the Lincoln design studio because, as they told Najjar, he was loyal to Walker and Engel and would do what they wanted. Although Najjar became head of the studio, according to designers there at the time, Engel and Walker really controlled and directed all aspects of the ’58 Lincoln’s design. Walker and Engel both preferred space-age designs, and they grossly misread the new-car market.

The ’56 Lincoln, designed by Bill Schmidt, was planned for a 3-year production run with yearly updates. Before he left in early 1955, Schmidt prepared proposals for the ’58 Lincoln. Because they was taking a run at Cadillac, Lincoln management decided they wanted an entirely new body style for 1958, not a warmed over ’56 Lincoln. Najjar was told that just as he was starting a redesign of the old body style.

Designers assigned to Najjar’s Lincoln studio, in addition to Engel, were Dave Ash (exec), Herb Tod (manager), Bud Kaufman (interiors), Rulo Conrad (peproduction), Art Miller (color and trim), Bob Chieda, Jake Alrdrich, Merle Adams, John Orfe, Joe Achor, Dick Schierloh, Bob Marcks Howard Payne, and Jim Swanson. Master modelers were Doug McCombs and Henry Klemick.

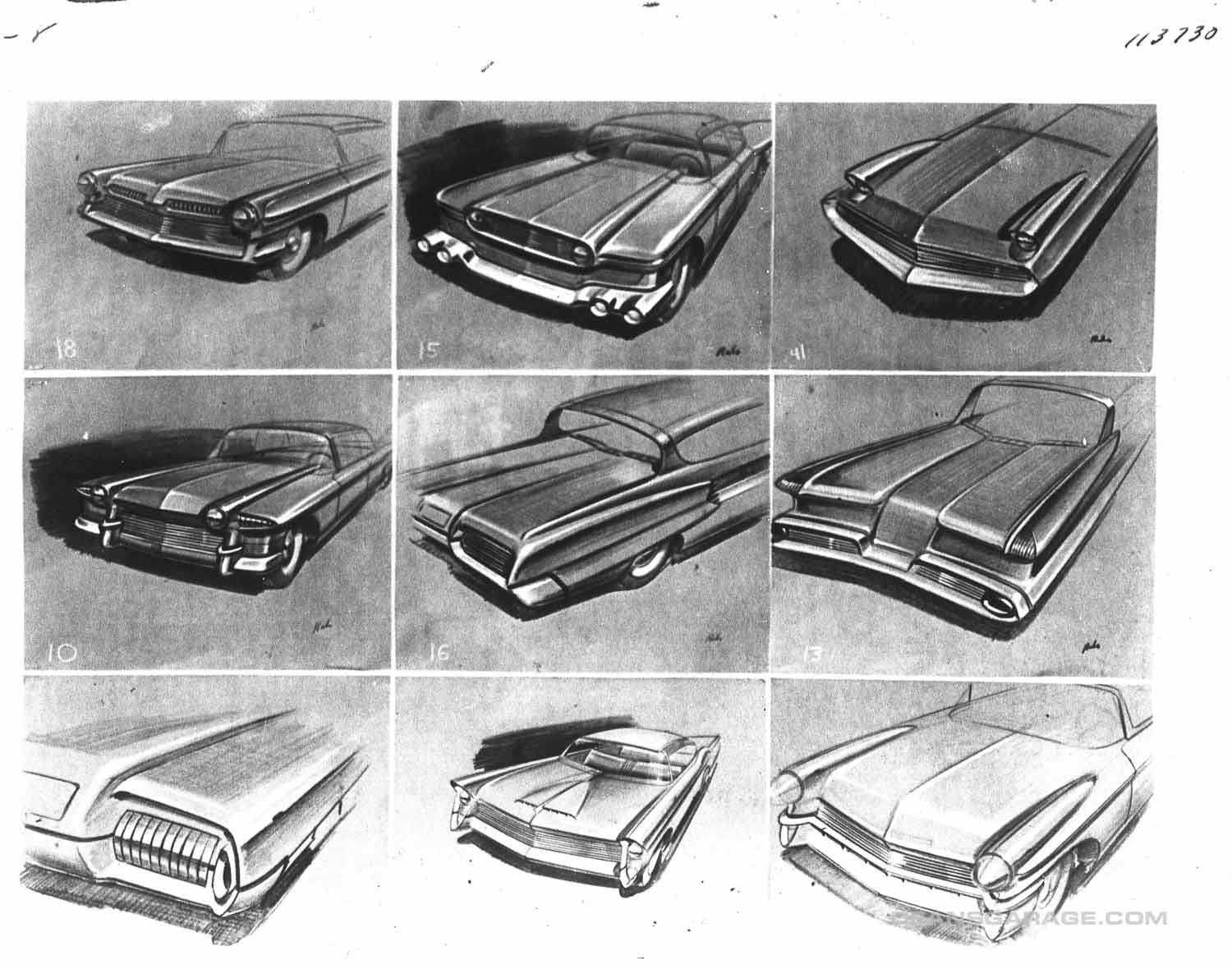

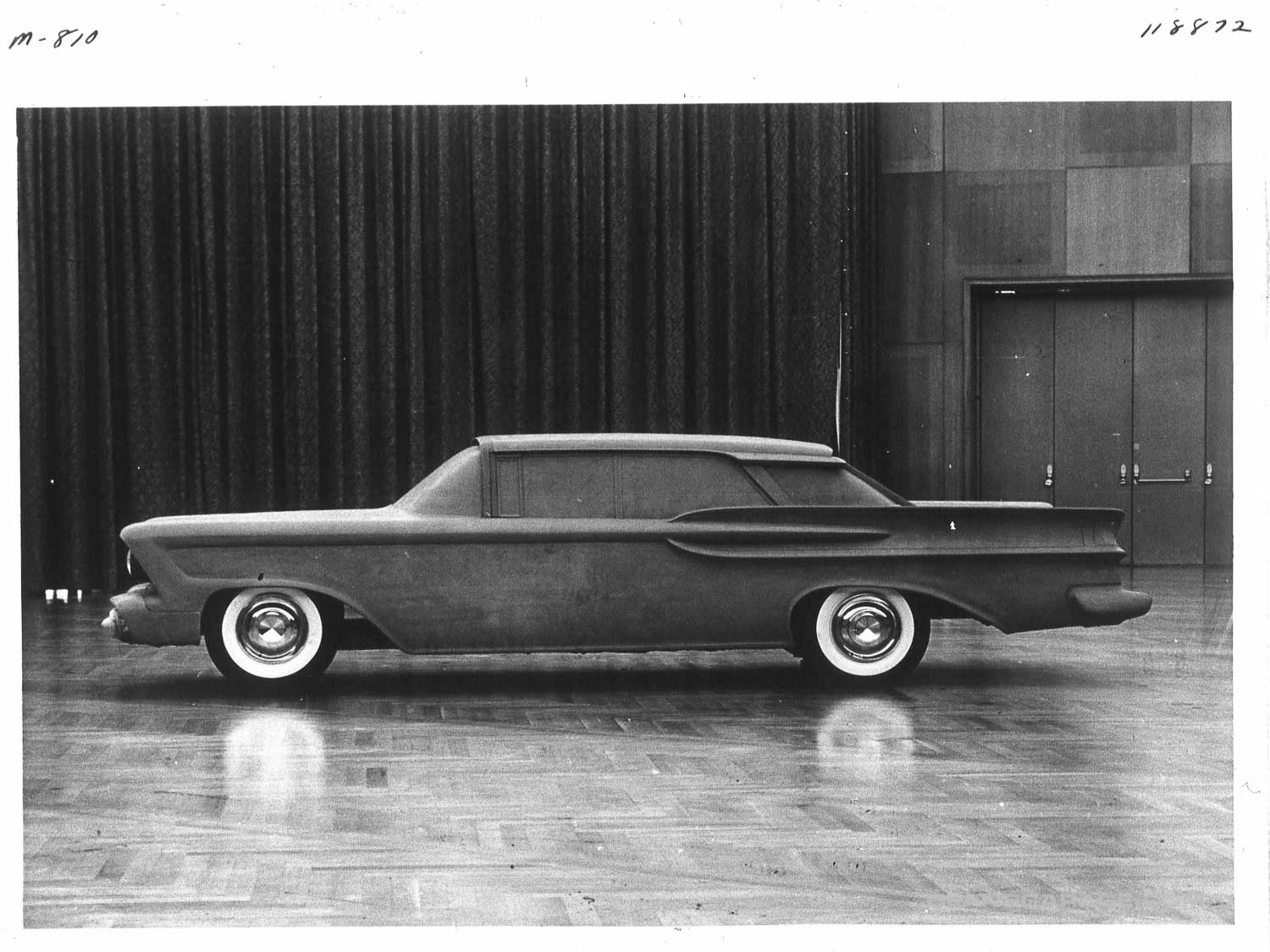

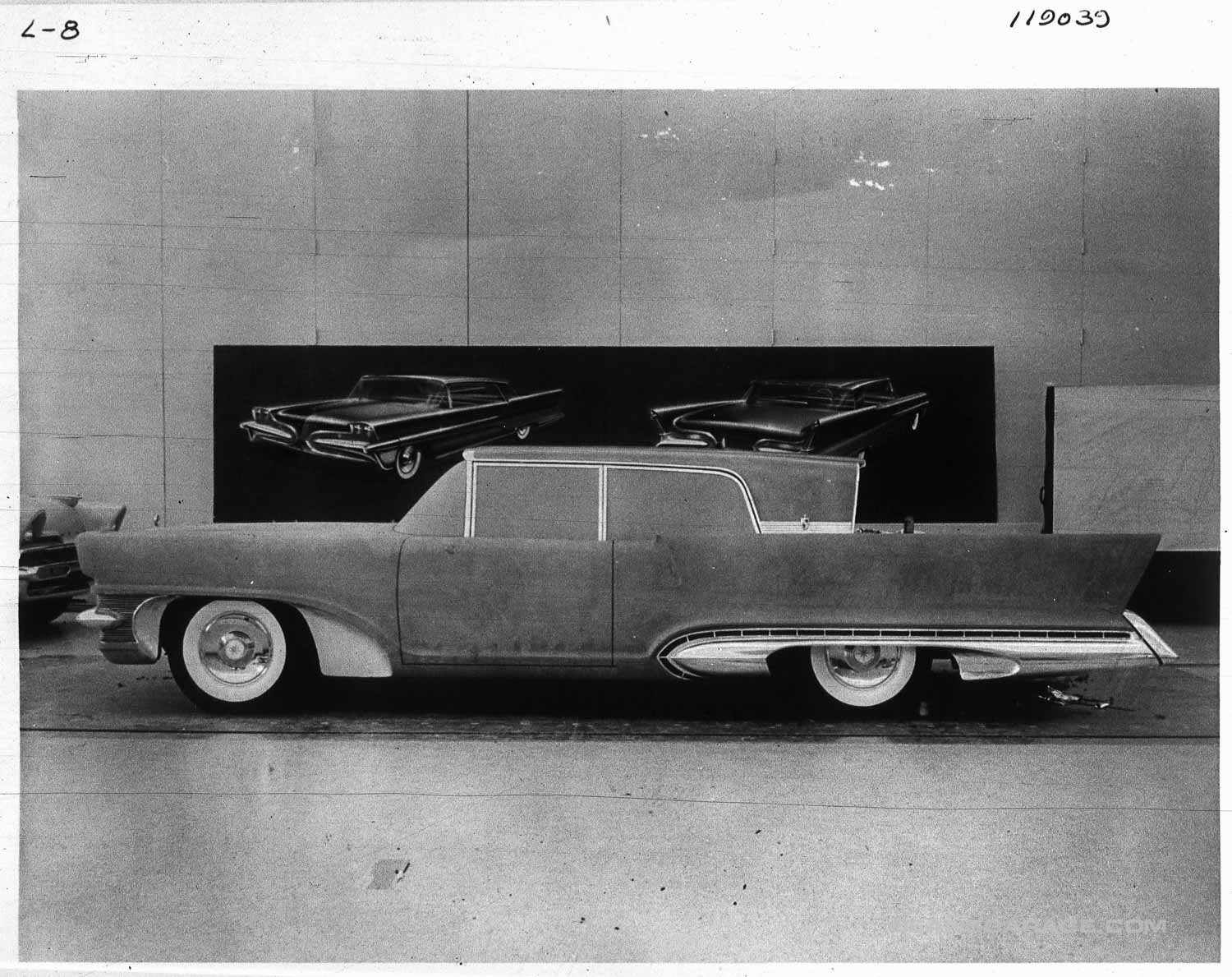

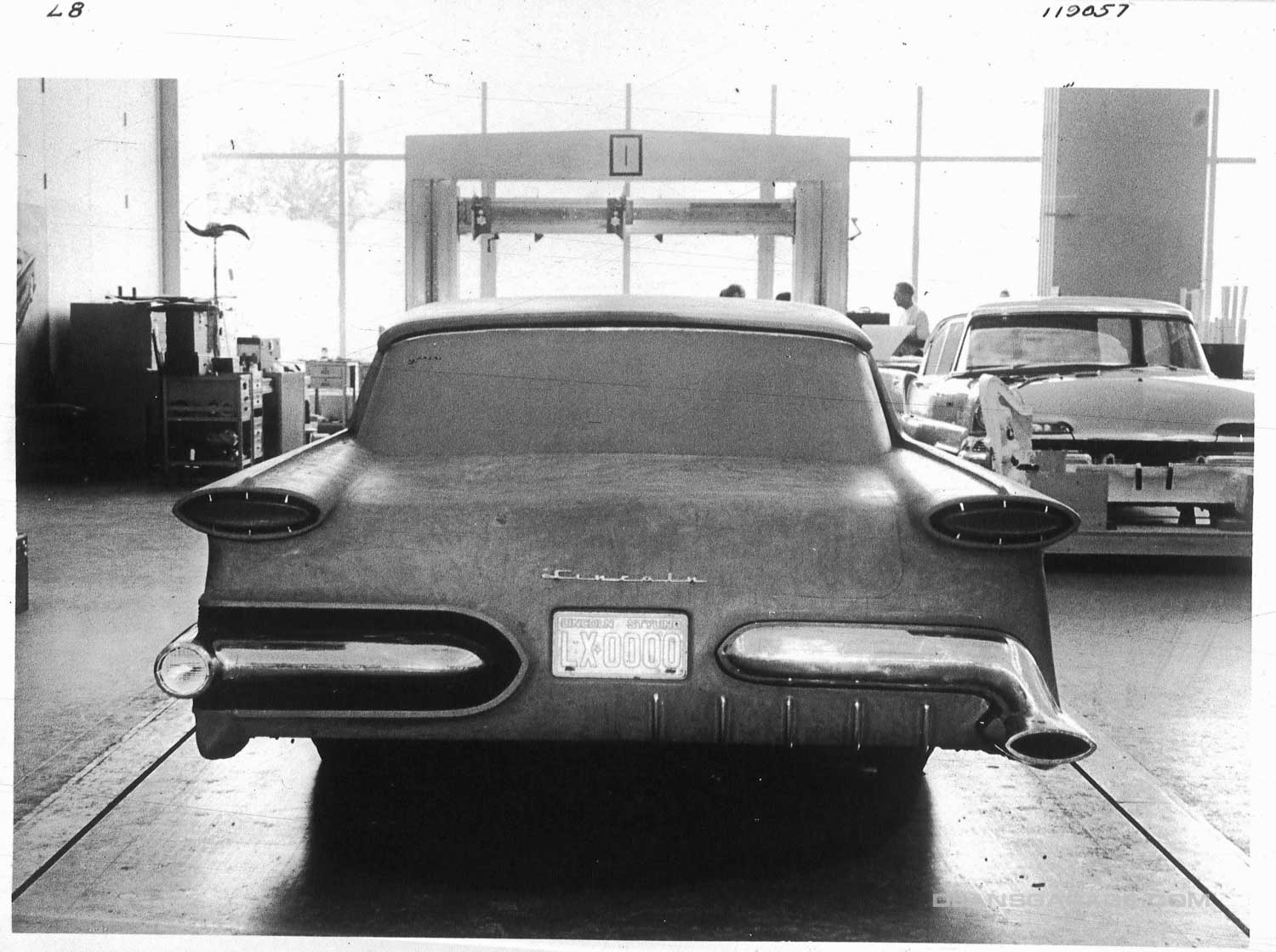

At first, Najjar and his designers had trouble coming up with a design direction that satisfied Lincoln Division and Walker and Engel. Directions from Lincoln Division were also clear as mud, which didn’t help. Engel solved the direction problem when he “drove” one of Alex Tremulis’ 3/8-sized motorized models called the La Tosca into the studio, where he told Najjar it was to be their design direction for the ’58 Lincoln. With little difficulty, Walker sold La Tosca’s “X over O” design theme to Nance and Lincoln Division.

After that, the design proceeded quickly, but when designers couldn’t come up with an acceptable front end design, Walker and Engel suggested that Najjar accompany them to the London and Paris auto shows to look for front end inspiration. At the London show, Walker and Engel were fascinated by the slant-eyed headlights on an English concept car called the Daimler Docker Golden Zebra—and by increasing the number of headlights it became the front end on the ’58 Lincoln.

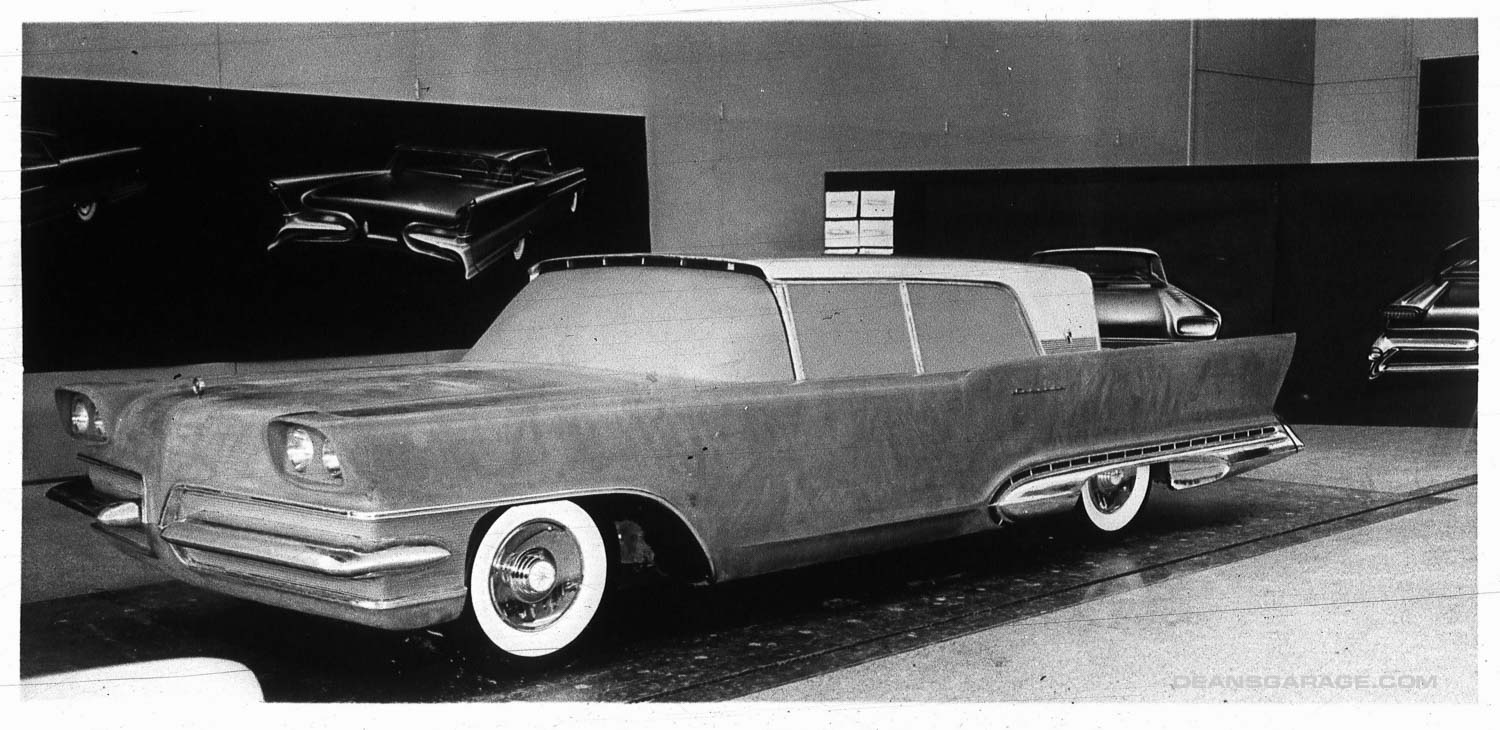

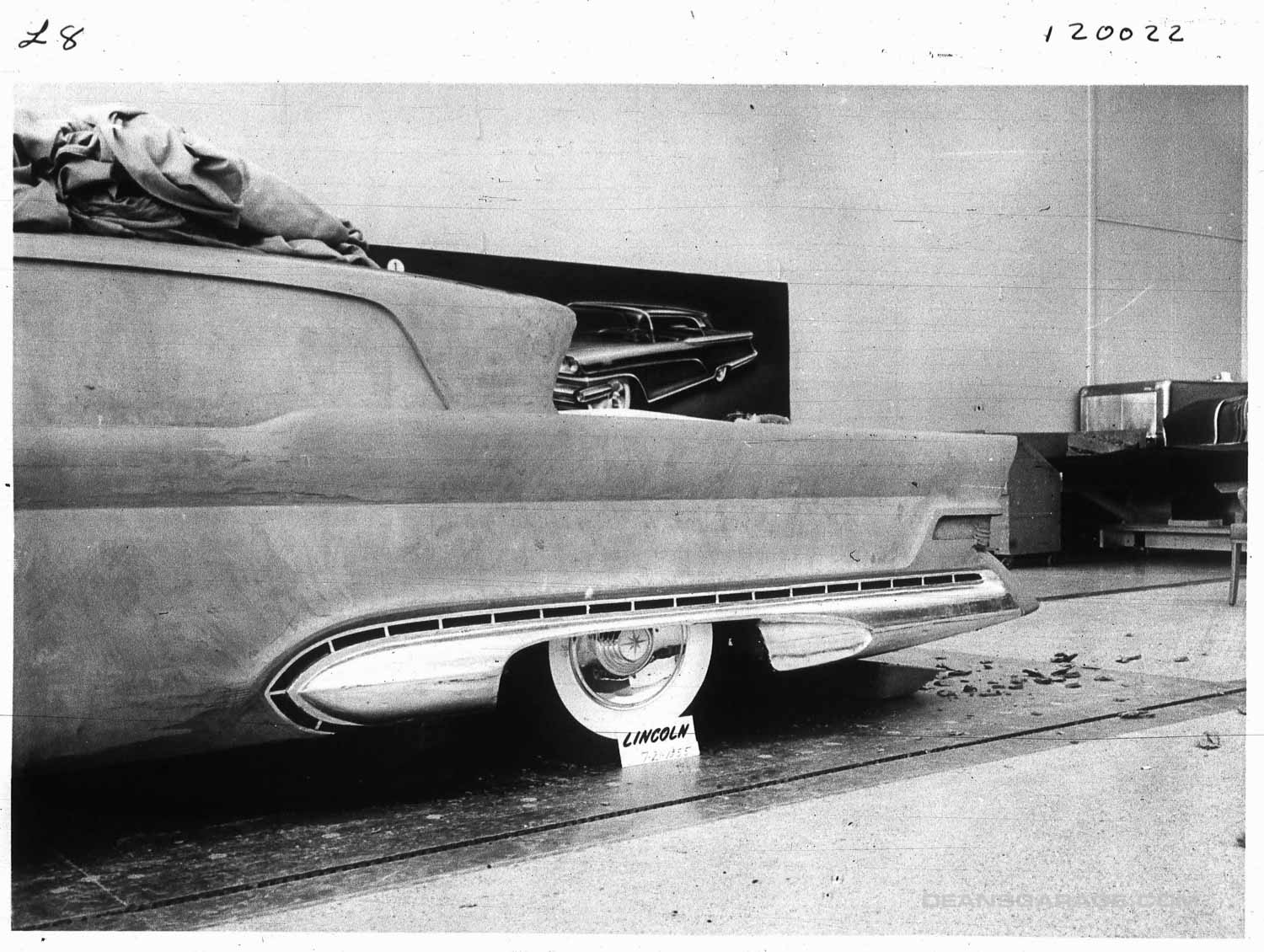

Originally, the 58 Lincoln was planned with a 126-inch wheelbase, the same as in 1956–57. In the meantime, the ’58 Lincoln got the new 430 CID engine, which didn’t fit in the 126-inch body without giving the car a front tunnel “big enough to put a saddle on.” Engineering’s solution was to just make the ’58 Lincoln longer, so it grew to a 131-inch wheelbase. Even after he retired, Najjar said the ’58 Lincoln was just too big.

Although he retired in 1957, at the time the ’58 Lincoln was being planned, Ford’s chief engineer was Earle MacPherson. He didn’t like designers and didn’t get along with Walker. And he was still smarting because in May 1955, design became independent and no longer a part of his Engineering Department.

MacPherson was told early on that Bill Ford’s Continental Division had avoided lengthening their Mark III, which also was to use the 430 CID engine, by employing an inexpensive double-cardin universal joint to lower the profile at the rear of the engine/transmission. MacPherson did not pass that information on to Lincoln engineers developing the ’58 Lincoln.

Problems compounded. After Robert McNamara became head of Ford Division, he decided to turn the Thunderbird into a sporty 4-passenger car. (McNamara’s very successful 4-passenger Thunderbird discovered a new personal luxury car market.) To get the car as low as McNamara wanted, the ’58 Thunderbird had to be unibody. The Thunderbird was slated to be built in Ford’s new Wixom assembly plant, but both McNamara and MacPherson assumed Thunderbird production would use no more than 1/2 of Wixom’s capacity. Their solution was to require that Lincolns use the other half of Wixom’s capacity, which according to MacPherson, meant the ’58 Lincoln also had to become unibody. Harley Copp, Lincoln’s chief engineer, told MacPherson it was folly to build a Lincoln that big as a unibody car. MacPherson’s response to Copp was to do it or quit.

When developing their proposed Continental Mark III, Continental Division had already come up with an inexpensive way to build body-on-frame vehicles on the same assembly line where unibody vehicles were built. Continental Division’s chief engineer at the time maintains he timely informed MacPherson of that information, but that wasn’t passed on to Lincoln Division either.

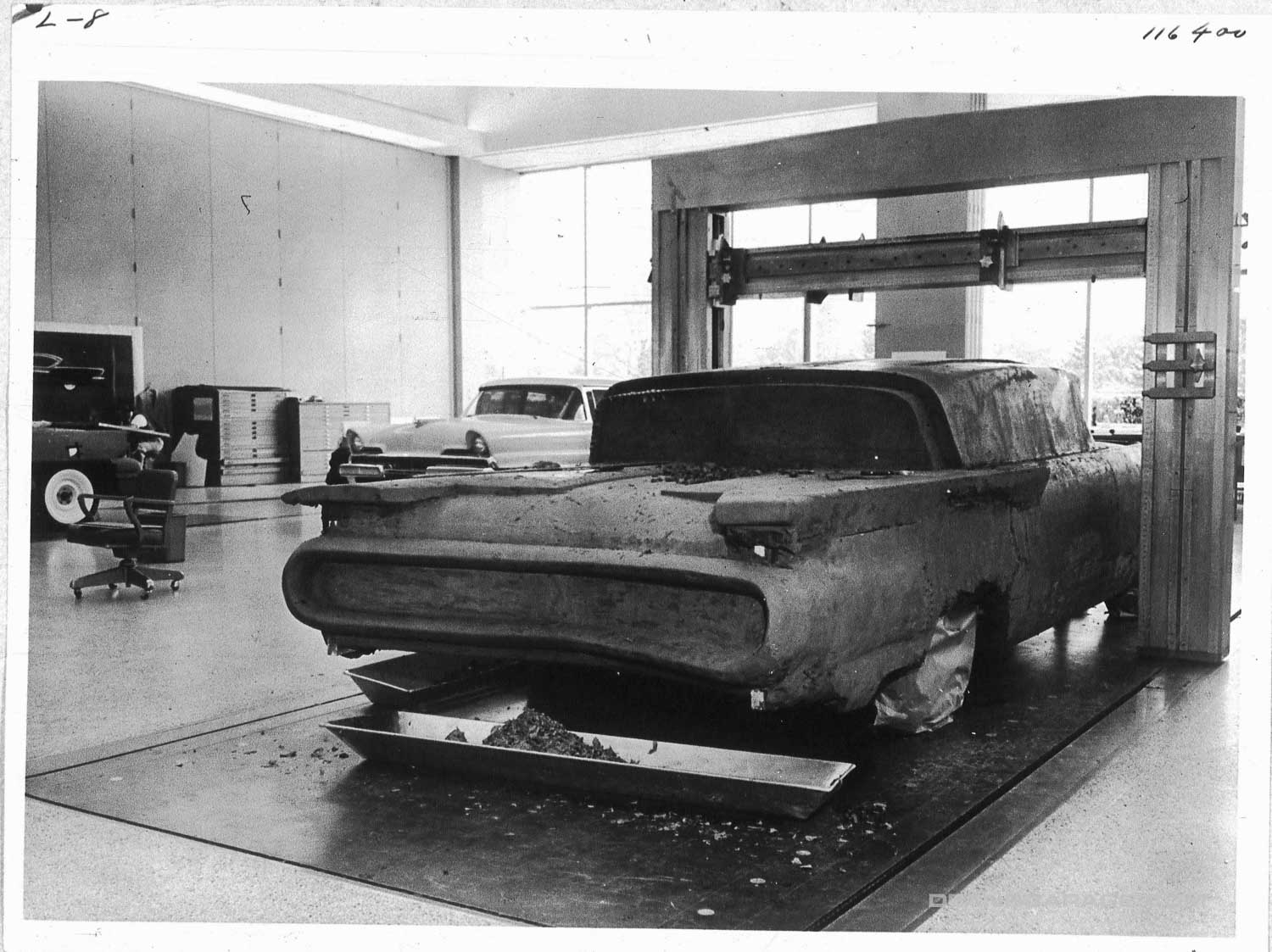

The end result was that when ’58 Lincolns first came off the Wixom assembly line, welds broke and it vibrated badly. On the test track, the ’58 Lincoln mechanical prototype actually buckled. Eventually, 200 lbs of gussets and a crash program was instituted to try to fix the car’s weld and integrity problems. Copp was right, but by that time, it was too late—or was it?

After Bill Ford’s Continental Division and its Mark III proposal were terminated in July 1956, Ford’s Executive Committee met at the Styling Center to consider building Continental Division’s Mark III proposal as a Lincoln Division Mark III. Ford’s executive vice president Ernie Breech, a committee member and still the number 2 guy at Ford, after viewing both proposals, suggested the better-looking Continental Division Mark III become the ’58 Lincoln. That suggestion got nowhere after Smith informed committee members that tooling on Lincoln Division’s car was already too far along to change. Lincoln Division’s ’58 Lincoln was produced as well as a badge engineered Mark III.

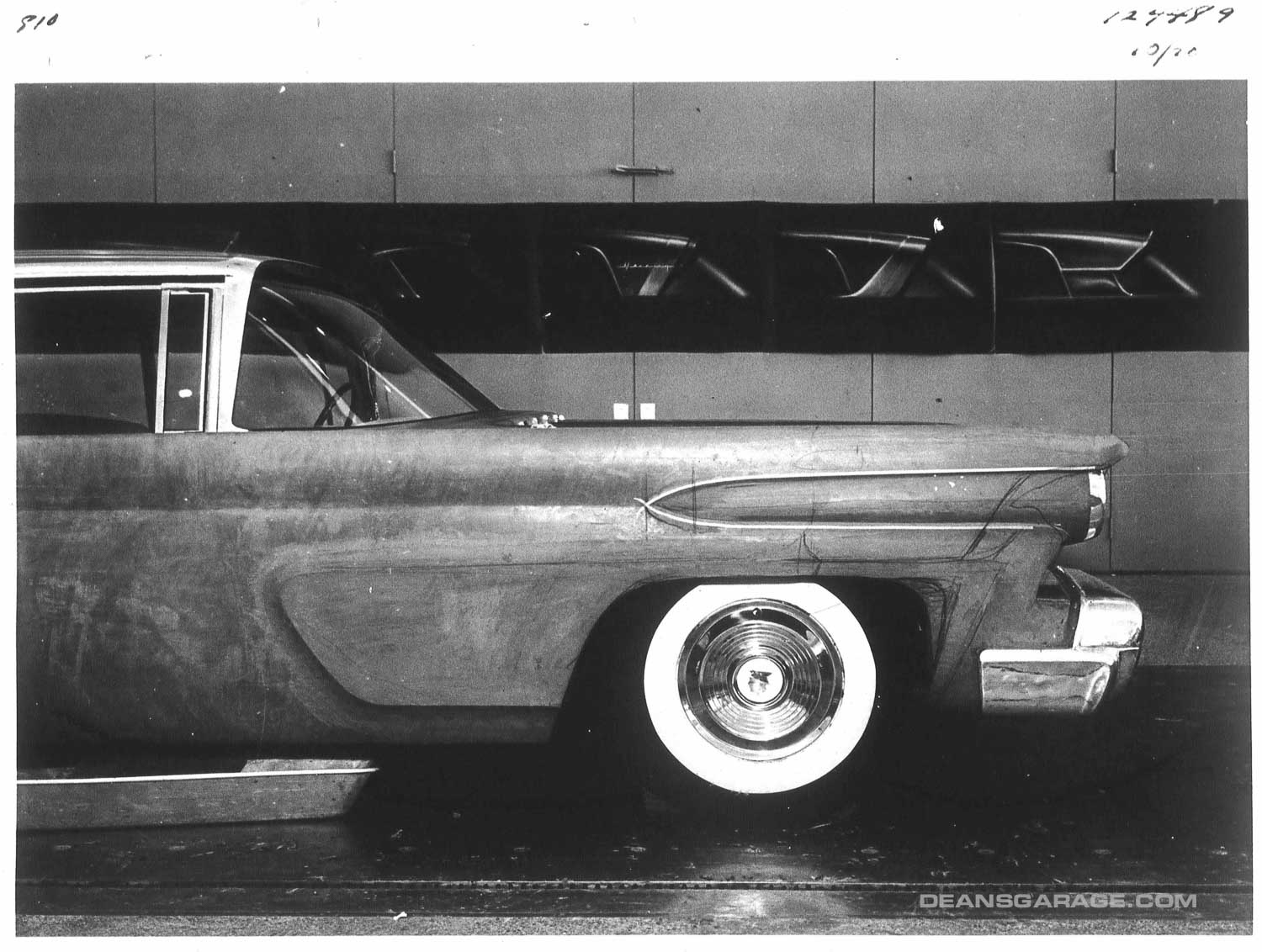

A month after he replaced Nance as head of Lincoln Division, Smith fired Najjar as Lincoln’s chief designer. He felt Najjar was too much under the influence of Walker, and that Walker had “sold them the wrong bill of goods.” Don DeLaRossa replaced Najjar as Lincoln’s chief designer, but he was unable to make any real changes to the 1959—60 Lincoln body style because of its unibody structure, and because the Edsel mess had dried up development money.

Given the paths not taken, the ’58 Lincoln, as produced, became the perfect storm. During 1958–60, Lincoln lost at least $60 million and half of its already weak market penetration.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

Interesting that there were any design influences from the famous, or infamous Docker Daimlers!

“Too many chiefs and not enough Indians.” Throughout its history, Lincoln has vacillated between two extremes of the styling spectrum – magnificent or atrocious. There’s no in-between.

One writer wrote (I believe it was in Motor Trend) “It wasn’t a very good year for Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln. But they still sold a lot of Fords and that’s what counts.”

I saw a lot ’57-’59 “Mercury” side sculpture in some of the posted images. It is really a shame about the breakdown in communication over personality issues. Had it not been for that, I am willing to bet that Continental Division’s Mark III probably was a better looking car. Considering how gorgeous and timeless the ’56-’57 Mark Ii was designed. But hey, McNamara’s idea of enlarging the upcoming ’61 Thunderbird turned out to be the saving grace for Lincoln for years to come. I really do wish that the contemporary Lincoln Division would give us another stunning tribute to the iconic 1961 Lincoln. And I do not mean that 2021 Continental either.

Is it true that, as the engineers did battle with the unibody issues, Lincoln engineers purchased a Nash Ambassador to research its integrity and strength in order to find a solution?

It is just my own opinion, but I very much like the 1958-1960 Lincolns, especially the 1960 Continental Mark V. The redesigned dashboard for that year is magnificent. I love the roof line of the Continentals with the retractable rear window. The power vent windows are also a very nice feature.

I never heard Nash had any influence on anything from M-E-L, but the 1955 probably had more than a little influence on the 1960 Ford.

Those Lincolns are hideous monstrosities. The Big Three’s longer-lower-wider, anything goes thinking in the ’50s seemed to be “never underestimate the taste of the American public.”

Space-age stying ran completely unchecked in the late ’50s. GM had the same disease, but its designs had more sophisticated and pleasing form development (unfortunately adorned with tasteless trim, complements of Harley Earl).

As the Lincoln was being developed in clay, it’s apparent that more time was spent coming up with adornment than surface development. The thinking of the time must have been we can save the thing with brightwork. Maybe the buyer will be swayed by glitter and look past the obvious.

The Big Three should have exercised some self-restraint. But the lack of same was embedded in the minds of decision makers. They never considered that this conceited attitude would ultimately lead to losing market share to imports that appealed to rational buyers.

Isn’t it so amazing that the executive committee and sub-committee processes, which are there to RATIONALLY discuss issues, real and potential, did not function. Once, in another life, I was an officer of a media company. Yes, I did not like dissent from many of those I managed. At times, it was hurtful, but most often the truth and candor made my stations better and I LEARNED something of which I was not aware. Was Harley Copp the only honest party in this sad saga ? Ernie Breech failed and Earle S. MacPherson should have been retired, immediately. The first test failure of the car’s structure should have been the red flag. 200-pounds of gusseting ? What a crock o’crapola ! There should have been an extended run on the 1957 “Futura”-inspired cars and a delayed introduction for a body-on-frame 1958 Lincoln, on a shorter wheelbase of say 126-to-129-inch wheelbase. Was Hank The Duece completely unaware of what was happening to his father’s child ? It seems incredible, but I know from my father’s time at Allison Engineering that G.M. was a hotbed of politics, too. Chrysler was rife with control issues, but had to answer to bankers. Boardroom issues killed Packard and eventually Studebaker. If I were H.F.II, I would have gone after George Romney, as he and McNamara would have probably been kindred spirits.

Excellent article! I’ve owned 5 1958s and 1 1960. They’re awesome to see and to drive. It’s interesting to see your photos of the Mercury-type clays. I’ve read that there was to have been a “Super Mercury” (Ford’s name for it) that was to have been a combination of some kind of both Mercury and Lincoln. I found just one 1956 color negative labeled “Super Mercury” many years ago at the Ford Photographic Archives in Dearborn that was pretty much a pre-production, un-nameplated Park Lane convertible. I took from it that the company had given up on the combination idea. I found a few other slides of basically (in terms of rendition) the same clay but a four-door hardtop version. They were newer than the original and had nameplates that said “Olympian”. Some minor trim changes later, and the “Olympian” became the production “Park Lane”. Your Mercury-types appear to predate what I found. Fascinating. Thank you!

These photos indicate a lot of bad input to the designers in the political chaos of the time. The designs are tasteless and confused. The production car somehow escaped the worst of the tinsel add-ons, but was just too ungainly in proportion to succeed, although it did seem very far out at introduction. Thank goodness the 1961 design saved Lincoln, and actually helped turn the the 1960’s into a better decade of design.

All was well and good with HF2 minding the Ford store. It seemed as long as Ford was working well, corporate meddling and oversight wasn’t needed at M-E-L, which was quietly taking on water rapidly by 1955.

I didn’t want to be the first to spear the 1958-60 Lincolns, but I knew I was in good company. The disease that overcame M-E-L, then hit GM didn’t stop there. Beginning with the Imperial, Chrysler had their turn at gut-wrenching styling faux pas that marred their image well into the early ’60s.

We affectionately remember the 1950s styling boom as the apex of the auto industry’s high-water mark. If the truth were told, there were perhaps more obnoxious exercises between 1958 and 1962 than there were timeless designs between 1949 and 1957.

These over worked, but under done busy, busy, BUSY “designs” sort of remind me of what passes for automotive “design” today! Even a 1958 Oldsmobile or Buick looks kind of ok next to these efforts, IMhO. One might wonder if “weed” was readily available back then; given that marker fumes were still some years in the future???

Curiously one of the few AMT survivors I have is the convertible version of this vehicle. Mine even has leather covered seats and 4 wheel coil springs….thanks to four ball point pens. 🙂

The “advantage” todaze automotive designers have is the CAID software they can use. Computer algorithms have no ability to recognize proper surface development, and that shows on almost every contorted SUV, car and pickup being sold today. Strother Mac Minn must be spinning. 🙁 DFO

—These designs were off the chart, and many of today’s main-stream offerings are off the chart in the other direction. Different era, same disease. Today with so many brands competing in a crowded marketplace with nearly identical packaging, they’re all trying to look different from each other. There are no rules. I remember being criticized at GM for sketches that had “too many designs on one car.” In other words, the were looking for designs with discernible themes. Memorable designs are those that you can capture the theme with just a few pen strokes.—Gary

In answer to the question posed by the headline, in a word, everything.

The executive dysfunction at Ford in this era defies belief. Luckily for them it didn’t spill over into the Ford division which paid the bills. It must not have been a good place to be if you were at a level where you had to deal with this corporate intrigue or its fallout. It must have been very discouraging to work in Ford Design amidst all this.

Aside from being far too big thanks apparently due to MacPherson’s dereliction of duty in not sharing how to fit the engine/transmission into the originally proposed body and also not sharing how to build both a unibody and a B-O-F vehicle at Wixom, some of the original concepts do not look totally awful given the state of automotive styling at the time, though I will never be a fan of reverse-slant backlights or angled vertical-stack headlamps. But with so many hands stirring the pot, what they ended up with was an oversized, over-surfaced, overly busy design. It’s a shame.

Interesting that Engel told Lincoln designers to follow the “La Tosca” rocket ship in designing the ’58-60 model. Is this the same Engel whose clean lined 61 T-Bird proposal grew doors and became the now classic 61 Continental? Did he have some epiphany between the two directions or was he just doing what would make George Walker happy? Too late for inquiring minds to know.

Lincoln was going to surpass Cadillac sales in 1958? What were they smoking?

Honestly does anyone think they didn’t pick the best looking of all the cars shown in the photos here to produce? The real question is how did they screw up the 1956 Lincoln with the 1957 and lose all that momentum? In my opinion it wasn’t the looks of the cars as much as it was the size. 58 and 59 where fine enough looking, but too big. They separated Lincoln from the rest of Ford and Mercury. Which is what a Luxury car line is suppose to do. But they did hit it the way the 61 Lincoln did. Again when you look at what could have been the 1961 Lincoln, they again picked the best design and this time it worked even though the car got smaller. So maybe had the engineer been listen to, and they right sized the car this wouldn’t even be a conversation.

The stunningly ugly, tasteless 1958-1960 Lincolns were the product of the same stylist who created the stunningly beautiful, sublime 1961 Continental, Elwood Engel, managed by the same self-promoting, strutting “Cellini of Chrome”, George Walker? How did this happen? How did such a turnaround happen by these same men in such a short period of time? One of life’s mysteries. Fortunately for Ford, their epiphany created the successful 1961 Continental and 1961 T-Bird (along with McNamara’s highly successful 1958 T-Bird and 1960 Falcon), restored Ford’s urge to innovate after the disaster of the 1958 Edsel and gave “The Deuce” the confidence to green-light the industry-busting successful 1964 1/2 Mustang. The 1961 Continental could have been named “Phoenix”…