Strother MacMinn, A Man of Wit and Genius

Published in Car Styling 56, Autumn, 1986

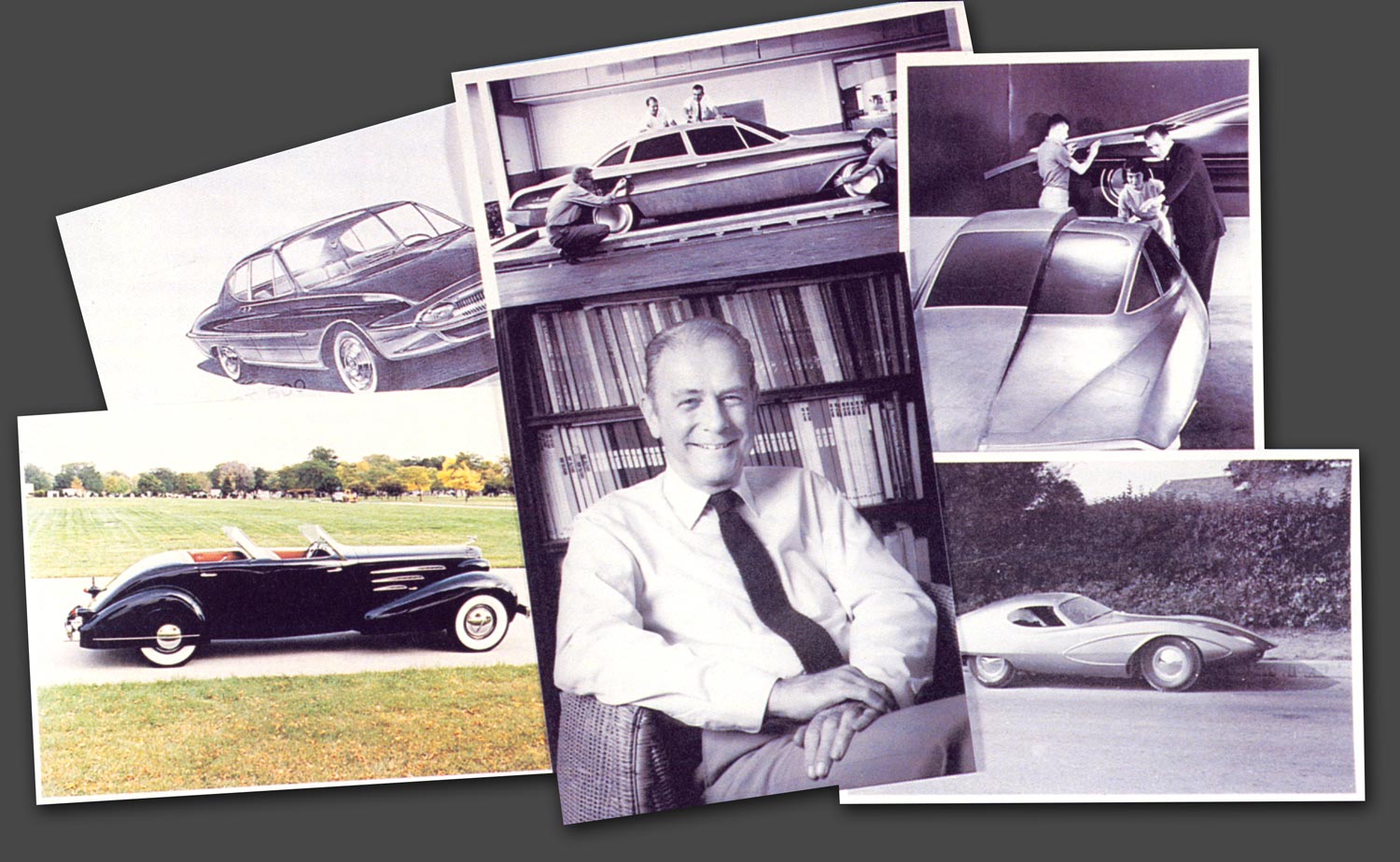

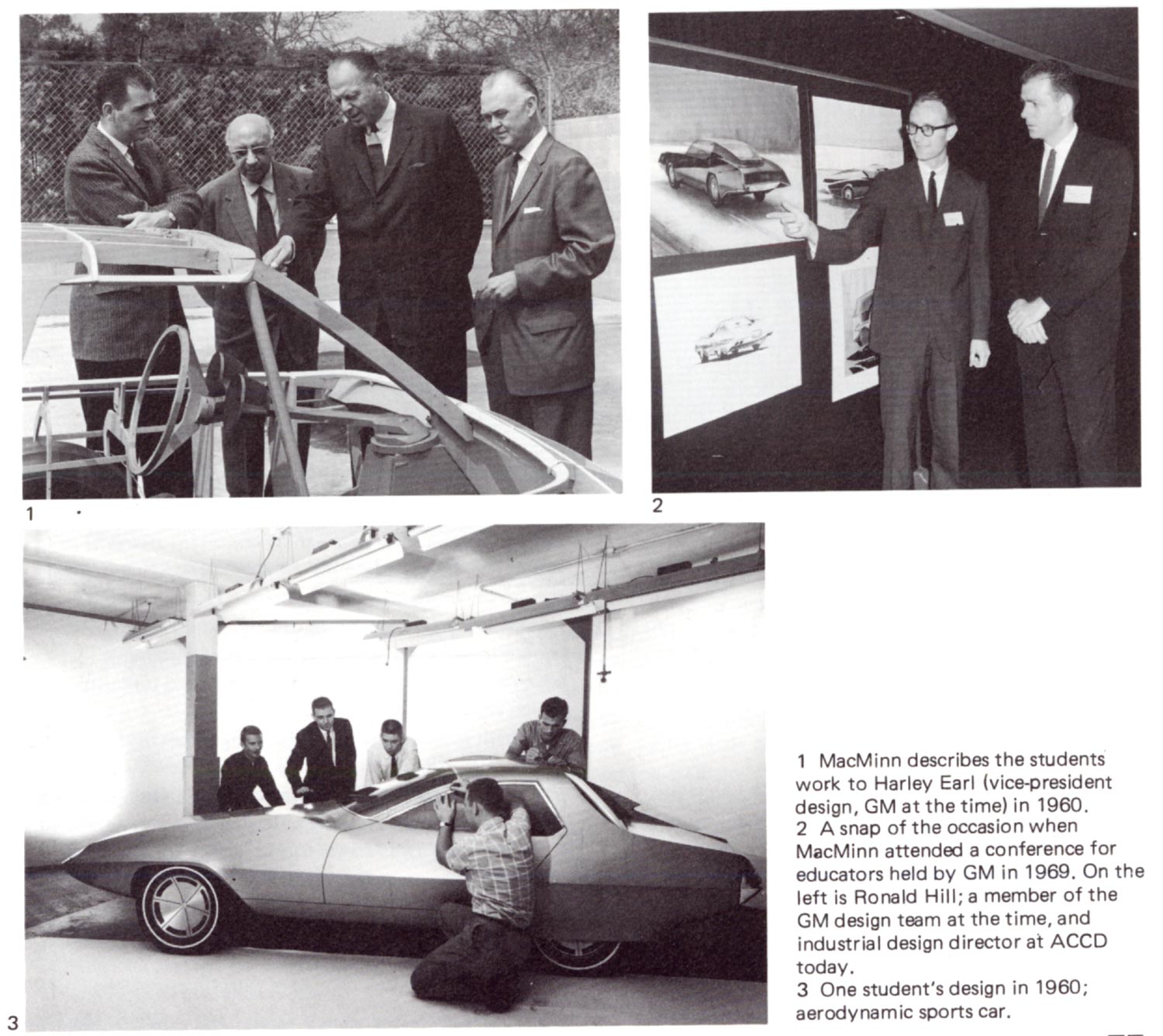

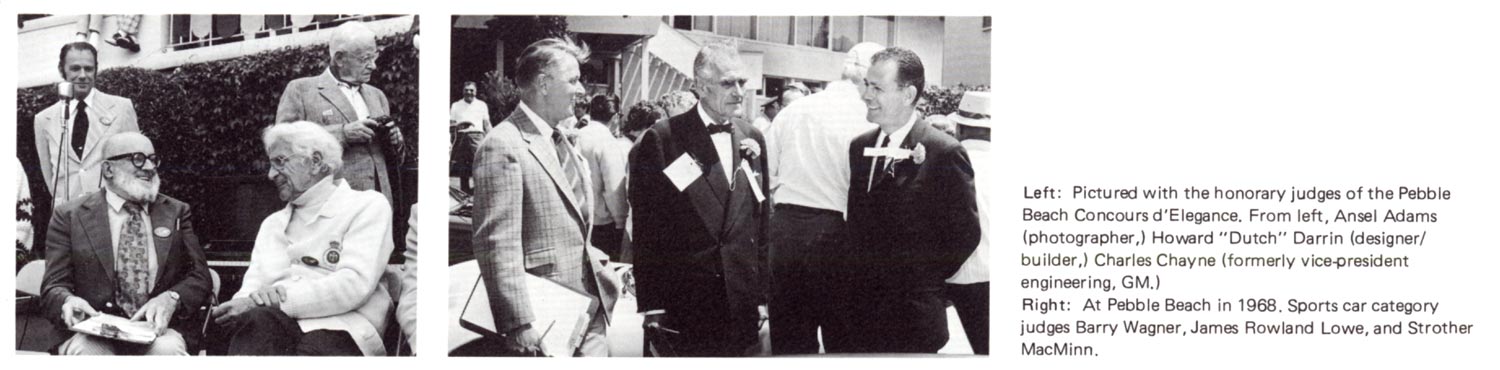

”A designer, a historian, a lecturer, a judge and a master teacher” is how Henry Haga introduced Strother MacMinn, the well-known and highly-respected member of the teaching staff at ACCD, when presenting him with the Lifetime Achievement Award from the IDSA (Industrial) Designers’ Society of America) at a symposium hosted by the IDSA and the JIDA (Japanese Industrial Designers Association) on June 14. ‘Mac,’ as he is affectionately referred to by his friends, has taught at ACCD for over 30 years, and many of the current executive designers internationally have received their training in his classes. Henry Haga, formerly design director at Opel and today Director of GM Advanced Concepts Center, is one of them. Mr. MacMinn is perhaps the only remaining designer who played a major role in the establishment of American automotive design, and he is also one of the world’s leading authorities on classic cars (being a judge for the Concourse d’ Elegance.) He has taught young designers the correct way to design over 30 years. When he talks of cars, a twinkle comes to his eyes; he is quick to smile and a man of keen witticism. Marianne Tremont brings us the following exclusive interview with Strother MacMinn to commemorate his award.

Strother MacMinn Report and Interview by Marianne Tremont

Q. Could you describe briefly your past and some of the major highlights of your life up to the present time, i.e., education, job experiences, etc.

A. It must be a terrible disappointment for many parents to discover that the child they have so carefully raised and hoped would become a doctor, lawyer, or even a musician, instead ‘wastes his time’ drawing cars—on the backs of tests, secretly in study hall, and on any blank sheet of paper in the back of a notebook. My Dad was a professor of English Literature and seriously hoped that I’d show signs of becoming a scholar like himself. He gradually saved enough money for my college education but he must have known all along that it was hopeless.

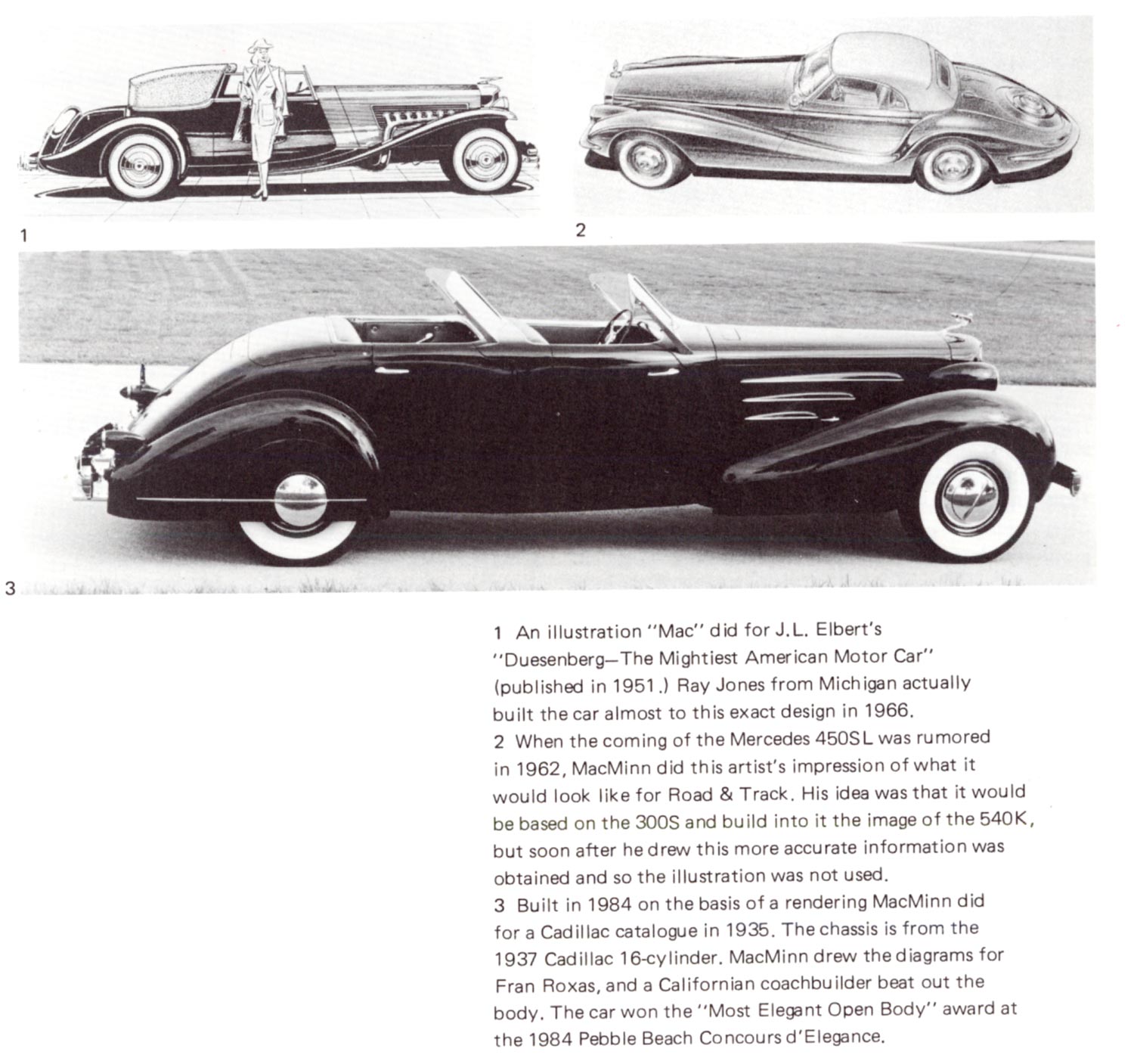

The world opened up the year that my parents gave me a bright, red bicycle and I rode it to every car dealer in Pasadena, gathering brochures and trying to get the salesmen to talk about the treasures in their showrooms. Then, one spring day in 1931, the gentleman at the Pierce-Arrow agency opened a drawer in the beautifully carved oak table in the center of the showroom and pulled out an original ink-line drawing of a custom body that was more beautiful in its proportions and craftsmanship than anything I’d ever seen—and I went crazy. Finally, the kindly salesman explained that it was a proposal from the Walter M. Murphy Company (just around the corner) to show to special clients and said ‘‘why don’t you go up and talk with the man who drew it?”

Reflecting for a moment, he realized that a thirteen-year-old boy wouldn’t have much luck getting past the receptionist in the front office, and then told me exactly how to go in the service entrance, up the back stairs, through the storage loft, and into the design room. Everyone should have at least one great turn of fate like that during their lifetime. Franklin Hershey was one of the best designers in that custom body business and was also a Boy Scout leader in his spare time, so he was friendly. After looking at my crude sketches, he offered to let me come up to the office on Saturday mornings when he could show me the basics on professional body design.

Downstairs, there were perhaps a dozen Duesenbergs, Packards, and Lincolns with bodies in various stages of construction. It was a whole new world! At the end of that summer |I went away to prep school on Catalina Island. By the beginning of the following summer the Murphy Co. had closed and Hershey had gone east to General Motors’ Art & Colour Section, but he came back every summer to visit his family. On each trip he would also look at my drawings and suggest improvements.

In the Spring of 1935 my parents had decided that a summer course at a recognized art school would be a good idea and I was enrolled at the Art Center School in Los Angeles. Even then it was the very best in the area because of the leadership of its founder, Edward A. Adams, and the professionals who taught there. It was also the beginning of a great friendship with two students who were in their final term, John Coleman and George Jergenson. After graduation, Coleman drove East and was hired by General Motors’ Art & Colour Section. It didn’t take long for him to convince his former room-mate, Jergenson, to do the same thing.

Finally, when I was about to graduate from high school, Hershey advised me to put a portfolio together and send it back with a request for employment. His recommendation, backed up by a few kind words from Coleman and Jergenson, must have helped because I was accepted and made the trip to Detroit in November of 1936.

The first job was working in the Buick studio where Hershey was the boss and, not surprisingly, Coleman, Jergenson, and Paul Browne were the other designers. The 1938 model was just being finished and they were beginning on the 1939 design theme that was to be entirely different including a whole new body series. On top of that, Harley Earl, founder and director of the Art & Colour Section had managed, in barely eight years, to assemble the most skillful and enthusiastic team of designers that he could find and it couldn’t have been a more exciting environment.

By March of 1937, Earl had received corporate approval that the newest product from GM’s German division, Adam Opel AG, should benefit from Detroit expertise rather than be designed in Risselsheim. He set up a new studio tucked away in the model storage area of Art & Colour, put Frank Hershey in charge with Hans Mersheimer of Opel to act as design liaison officer, and gave them the assignment to style the up-coming 1938 Kapitan model. The studio cadre included experienced technical personnel from a variety of sources, but Hershey was allowed to bring Coleman, Jergenson and myself along with him from Buick. It was an exciting enterprise because of its new approach to international styling and that we were allowed to propose more advanced ideas than the regular division studios. We were able to use special, built-in headlights in the front fenders, stretch the fenders on into the front doors, and eliminate the customary bright belt-line molding to achieve a much cleaner body form. (That basic model, with face-lifts, remained in production into the early fifties.)

When the project was finished at the end of May, Hershey went to Europe with Mersheimer to supervise the production of the design. Jergenson went back to the Buick studio, Coleman to Chevrolet, and I was assigned to the Truck & Coach studio that did all of GM’s trucks and offered styling proposals for GM’s major, inter-city bus client, Greyhound Lines (in competition with industrial designer Raymond Loewy).

There was a business recession in early 1938 that led to a reduction of Art & Colour personnel as an efficiency measure. I was released, but before leaving Detroit I interviewed at both Ford and Hudson and, six months later, was offered a job in Frank Spring’s styling department at the latter. It was a small but unique group of designers that included the enormously talented Bob Koto (who finished all of his proposals in scale clay models) and Jack Aldrich (who had been one of the first members of Earl’s Art & Colour Section).

Our work was mainly in face-lifts and details because Hudson’s cash flow wasn’t enough to afford all-new bodies at that time. Koto did develop a radical proposal with spring that featured a perimeter frame, but it was put in storage. Ten years later they revived the design and used it as the basis for the new 1948 “step-down” Hudson. Finally, in the spring of 1939, word got around that GM was hiring back some of the people that they had let go. After my interview with Howard O’Leary, Earl’s administrative assistant, being accepted felt like ‘’going home.” This time it was to the Oldsmobile Studio with Ed Anderson in charge and John Foster, Harper Landell as the other designers. Harper left later and was replaced by Roy Brown.

We finished the 1940 models and then did all of the ‘41 and ‘42 cars including some interior details such as instrument panels. ‘Invited’ by the military draft in February, 1941, I spent time with an infantry regiment before attending officers’ candidate school and then being assigned to an Air Force P-38 fighter squadron (as ordnance officer) and going to England. Then it was with P-51’s in Belgium before returning to be discharged.

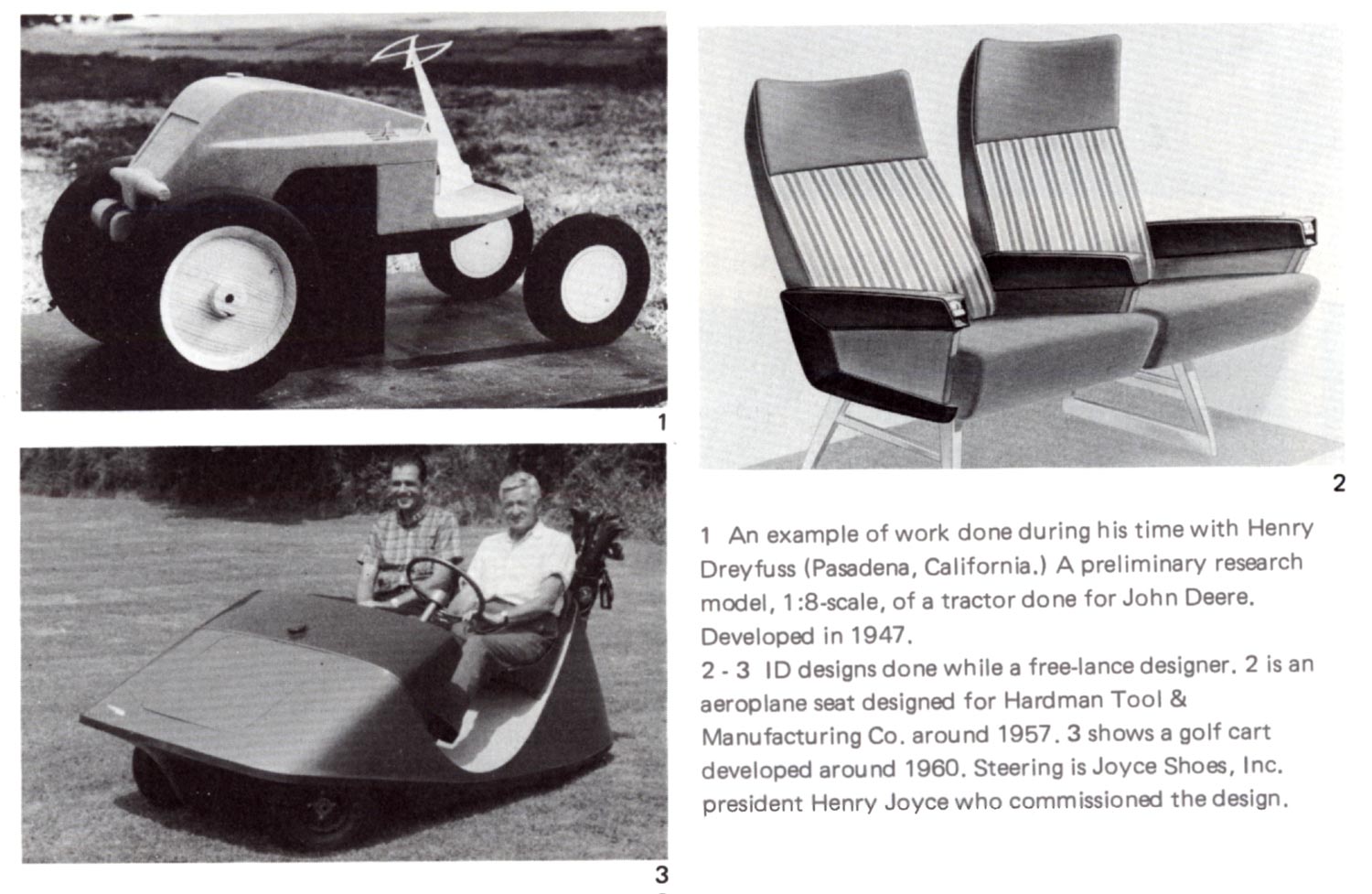

Six more months back at GM, this time in a special advanced studio with Hershey, before eventually resigning, working on a farm in Ohio for the summer, and then coming back to California to work for Henry Dreyfuss who had just opened his West Coast industrial design office in Pasadena. Jergenson and Coleman had been hired by E.A. Adams to re-organize Art Center’s industrial design department in late 1945. After visiting them in 1948, Jergenson offered me a part-time job teaching and that had to be the best job offer anyone ever had. There is nothing that can compare with the excitement and stimulation of sharing enthusiasm and knowledge with dedicated, professionally-oriented young students at a first-rate institution such as the Art Center College of Design. It also is an opportunity to develop international friendships with designers from overseas automobile companies.

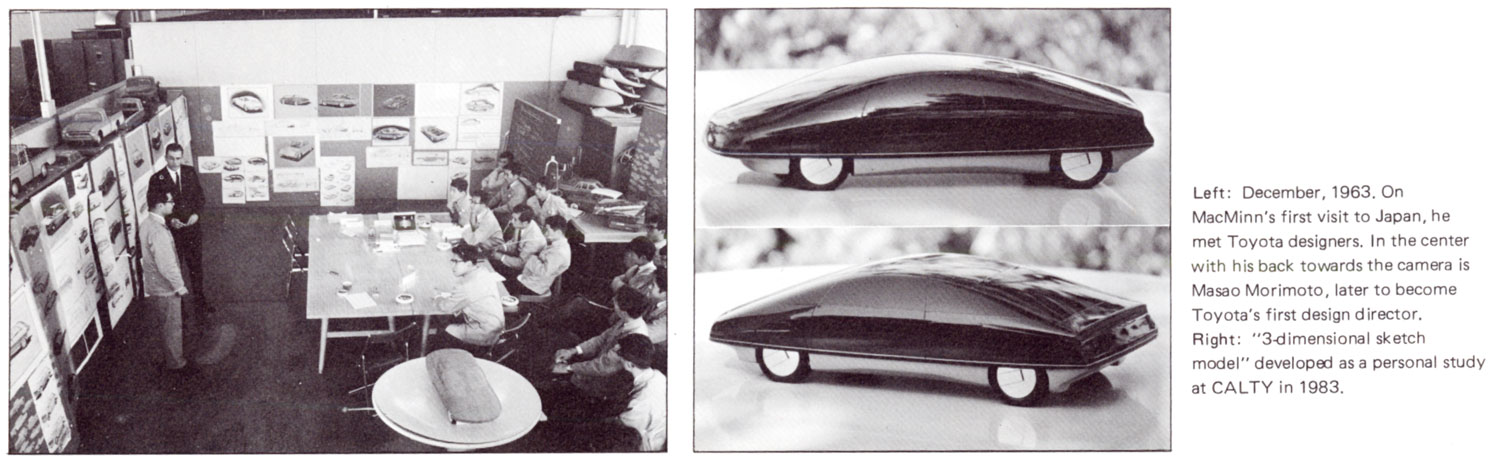

Masao Morimoto, then Head of Design for the Toyota Motor Co., spent two years at Art Center in the mid-fifties before returning to expand his staff to keep pace with Toyota’s position as the primary Japanese auto manufacturer. In 1963, I was invited by him to spend two weeks in Toyota City as a consultant. We then introduced a special, one-year, advanced design program for professionals at Art Center. A total of fifteen Toyota designers (and quite a few from other Asian as well as European auto manufacturers) have participated in this program which continues today.

In 1972, Masahiko Kaneko (a 1971 Art Center graduate who was founding Car Styling Magazine with San-Ei Shobo Publishing Company) was successful in proposing that Toyota establish an advanced design studio in Southern California. We consulted together on personnel candidates and, by July 1973, were successful in bringing together the first nucleus of design and fabrication talent. My ten years spent working with that unique, pioneering organization were, perhaps, the most rewarding of the whole career because of the genuine honesty and sincere concern displayed by all of the executives of the parent organization. When you’re working with that kind of attention, you do your very best. All of us were greatly privileged to be educated into both Japanese business principles and the rich, cultural background in which honor and artfulness are principal elements. We were also able to develop lifetime personal friendships among our counterparts in the truest international style.

Q. For 50 years you have viewed car design. What is your analysis of the design changes you have seen over the year? i.e., trends or technical improvements, stylists vs. designers?

A. When I entered the automobile design profession in 1936, styling had been clearly established as a unique and separate function of the marketing program. Harley Earl, operating under the direction of General Motors’ President, Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., was the dominating force with his Art & Colour Section, but Ford and Chrysler had also established their own styling departments. In addition, the major production body suppliers (Briggs Manufacturing Co., Murray Body Corp. of America, and the Budd Co.) had their own complimentary design staffs. The design process was intuitive in every case. Decisions within the design organizations were governed by the personal insight and emotional response of the managers who then ‘‘sold”’ the ideas to corporate engineers and directors, often using dramatic techniques and skillful political manipulation. It was certainly colorful if not predictable! In fact, the search for “new” styling ideas (rather than the ‘‘ideal’’) tended to accelerate design progress overall because of the demands made on production systems and engineering to solve new kinds of problems.

The designers, themselves, came from nearly every kind of background imaginable because there were no schools with programs aimed directly at the auto industry then. Most good designers have a broad range of interests anyway, so some were educated in architectural design while others had studied illustration and painting or even interior decoration. It was all art of some kind. A good design studio would combine three or four designers with different backgrounds in order to have a broad balance of idea input and display capability. The real heroes were the hard-working studio engineers (draftsmen) who made the endless working drawings, and the clay modelers who could resolve impossible surface transitions into sculptural works of art. Maybe because their tasks were illogical, the clay modelers developed a wry and often ironic sense of humor that could keep a studio lively, even when working on overtime.

The biggest changes that have occurred since then have been the narrowing of the gap between engineering and design, and the emergence of intelligent market planning based on appropriate research. Now, the designer’s first approach to an assignment might be an intuitive exploration, but the idea’s immediate evaluation is based on how it can improve a future marketing opportunity and how it can use the latest advances in technology. That maturity and awareness that occurs ‘’on the board”’ is the result of some very specialized education in industrial design departments of conscientious colleges who feel a real concern for professionalism. Not only do they attract the top layer of talent and assemble it into peer groups filled with ambition, but they maintain a close liaison with all forms of industry so that their process can anticipate growth in the state-of-art. The obvious result of this refinement is that its nearly mandatory, now, to have a degree from an accredited school or college in order to be a candidate for employment in a design organization. The biggest handicap to this system is that it costs a lot of money to go through the process (and that doesn’t always guarantee immediate employment), even with the partial assistance of scholarships and government grants. Hopefully, in the not too distant future, subsidies will make it possible for anyone with genuine ambition and skill to complete a degree course in industrial design as a prelude to maximum cultural development.

Q. To some extent, design educational institutions are incubators for the designers of tomorrow. Being an educator for over thirty years, what changes in educational methods have you seen that have had a major influence on design directions?

A. Mainly, more accurate simulation of the actual process in professional design development from idea generation (initial sketch) to finished proposal and presentation. Emphasis on human factors and ergonomics combined with an awareness of engineering principles and marketing trends helps to lay a foundation for appropriate design that doesn’t necessarily inhibit the designer’s imagination or unique sensitivity. Communication skills (meaning sketching, rendering, and modeling) are a great asset to talent display, but being able to verbally and quickly describe a design adventure to a supervisor or executive is just as essential. A little personal drama also helps.

The biggest change has been in the ability to present a fully-detailed design proposal in full scale, either 2-dimensionally or 3-dimensionally, and that represents a specific element in a corporate marketing program. Art Center students recently went even further by completely face-lifting a production sports car in only seven weeks and thus presenting a running prototype. The confidence and pride generated by such a project is beyond evaluation.

Q. What changes do you see, if any, as necessary for design students’ education to better prepare them for entry into the design world of today?

A. In addition to the principles and techniques just described would be an encouragement to accept responsibility in any creative environment that is considered employment. Many students come into an educational program looking for an opportunity to polish and improve their sketching techniques when that’s only the first step in idea presentation. Education is really an awareness of need and mastering the process of inventive problem solving, particularly where profit-making is a primary motive. One of the most important elements in technology that has recently entered the design process is the use of computers for information retrieval, complex volume analysis, and graphic display. The graduate who can really manage and use a computer has an enormous advantage for candidacy in both today’s and tomorrow’s design world.

Q. With economic factors impacting so heavily on the car industry in the past decade, the past few years has produced a homogenized look in car design. Being a leading authority on classic car design, do you see a way in which designers today can extract the originality and beauty of the classic car and implant that look and feeling into cars of tomorrow?

A. No. (!) The best thing about classic car design was its honesty combined with great refinement and quality in its execution, Those principles are always admirable in any era but retreating toward a past ideal would be like closing one’s eyes to imagination and the future. The answer to the homogenized look lies in the courage and skill to invent new ideas and even principles, and then being able to ‘‘sell’’ them to a cautious management.

For instance, it was thought, in the past, that body surfaces on a vehicle could be accurately judged in a static or non-moving condition. Now, the character of a body must be evaluated in motion because of the changes in proportion that occur in transition and the flow of reflective pattern that gives a body a sense of grace and efficiency. Out of this comes a whole new attitude toward 3-dimensional form and how it can accurately imply a desired character. Use of this awareness encourages an overall sense of design rather than the first tendency to ‘‘assemble’’ favorite details and clichés from personal preference.

Q. Upon what personal event or time in your life did you see as the turning point that helped you develop your own design philosophy? (Please describe your personal design philosophy.)

A. The first influential experience was meeting Franklin Hershey, designer at the Walter M. Murphy Co., and appreciating the clean balance and accurate proportions of Murphy coachwork when I was thirteen years old. Henry Dreyfuss’ style of industrial design was also artful and logical. The five years that were spent in his office in both Pasadena and New York were a tremendously important education into both style and responsibility, from 1946 through 1951.

Finally, the need to examine and explain principles in design as an educator is an on-going responsibility for understanding fundamental principles combined with style as it changes. My personal preference in design is to find the most truthful, single statement that will represent the function of the article being designed and then ‘tune’ it with a dynamic enclosure that will imply grace, strength, and exciting performance.

Q. What individuals in the history of Industrial Design and automotive design do you feel had the greatest role in changing design directions?

A. Certainly the ‘‘godfathers” of Industrial Design deserve the first credit because they identified it to the business world that they served as well as to the consumer. These would include Harold VanDoren, Henry Dreyfuss, Walter Dorwin Teague, Raymond Loewy, and Norman Bel Geddes.

Dreyfuss, Loewy and Teague collaborated in their suit against the State of New York (which they won) that legally established the profession in 1930. They also founded the Society of Industrial Designers (that later became the IDSA) as a qualified professional organization to uphold standards of performance and ethics.

If the ID profession was first recognized and taught at the Bauhaus in Germany, then its philosophic origins belong to Walter Gropius and Moholy-Nagy along with all of the other architects and designers who participated in that revolution. They laid down some basic principles of design that are still valid today, although the application of style has changed.

Running through a list of style eras, from Victorian to Art Nouveau to Art Moderne and Art Deco to Post Modern, would indicate a popular palette from which designers were able to draw. The same is somewhat true of automobile design. The early aerodynamicists such as Paul Jaray and Keonig-Faschenfeld influenced stylists to adopt truthful and graceful forms.

Unquestionably, Harley Earl recognized the public’s appetite for drama and even novelty and used complex applications to stimulate sales. His power as a leader created waves of imitation throughout the industry. Gordon Buehrig, inspired by the architect Le Corbusier’s sense of space philosophy, created a milestone composition of simple, original elegance (the 810/812 Cord) in the middle of the transitional thirties, but no one was able to follow it with any success.

The one name that stands out in modern times as having clearly influenced more than a decade of automotive design is Georgetto Giugiaro. Other designers who achieved great artfulness in their works were Henri Chapron, Raymond Dietrich, Virgil Exner, Franco Scaglione, Amos Northup, and Howard “Dutch” Darrin.

Q. Where do you believe a designer’s creativity Originates? Is it practical knowledge and dexterous skill or is it more psycho-spiritual in origin?

A. The ability to solve problems in an artful way is certainly a product of heredity, environment, experience, and discipline. Adding educated skills is a refinement.

Q. Do you consider it essential that a designer maintain some type of moral standard, given the fact that they are creating and bringing to life an object that will actually exist in the world? i.e., Are designers responsible for ‘‘visual garbage”, safety of consumers, product usefulness, etc.?

A. On the title page of his book, Designing For People (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1955), Henry Dreyfuss states: ‘‘We bear in mind that the object being worked on is going to be ridden in, sat upon, looked at, talked into, activated, operated, or in some other way used by people individually or en masse. When the point of contact between the product and the people becomes a point of friction, then the industrial designer has failed. On the other hand, if people are made safer, more comfortable, more eager to purchase, more efficient—or just plain happier—by contact with the product, then the designer has succeeded.’’ Conscience, then, is one key to successful and rewarding design work.

Q. What last words of advice would you like to address to the designers of the future?

A. Don’t be afraid of anything but your own ignorance. Do not respond to provoking arguments. The title of Raymond Loewy’s first book on industrial design describes every good designer’s worst problem: Never Leave Well- Enough Alone—the tendency to want to continue with the design development past the deadline. Give everything that you do your very best effort and, when its finished, look forward to the next chance to improve on what you have done.

Being a leading authority on classic car design, do you see a way in which designers today can extract the originality and beauty of the classic car and implant that look and feeling into cars of tomorrow?

The answer to this question is the saddest. Todays cars for the most part are a visual disappointment.

What a great story and insight to design. Dean, thank you for this article and sharing the wisdom of the people that -MAC – influenced. When I read stories like this it makes me so proud to be bringing MAC’S LEMANS COUPLE back to life so other students and young kids can enjoy . WOW —THANK’S AGAIN DENNIS KAZMEROWSKI

Dean. I also wish to thank you for stunning article on ” Mac ”

As a young Designer at Ford…some of my design friends were having a summer house party in Dearborn. I think it was at Ken Dowd’s and Larry Griffin rental home. Interestingly young Designers from Ford, GM, Chrysler, AMC…and represented

From all the main schools…… The magnetic draw to this fun Summer event, was that the Infamous Strother MacMinn would be in attendance.

WOW……the street was crammed, the house was full….and I finally met this great legend of Design Inspiration. He was just super gracious…really humble, just a wonderful man.

I only met him that one time, but I immediately understood how truly wonderful and endearing he was with ALL his students and all designers who were engaged in this wonderful automotive process of Industrial Design.

Sincerely, Christopher Dowdey.

ex Ford Design. ASC International Design

Nice story telling and glad it’s available for scholars and people interested in the true history on how the auto design profession came from America. This piece on Strother MacMinn helps strengthen the overall narrative of exactly where “Car Styling” and/or the “Car Design” profession originated in the first place. Here’s a succinct link of material on the birth of Car Design: http://www.harleyjearl.com/what-we-do

This is a story well worth repeating, for those not knowledgeable about the history of industrial design and the key people involved. It should be repeated every few years!

I wish to pay the history forward by offering my 153 CS (English/Japanese) Car Styling (first 45 issues of CS hardbound) & 7 Auto Style (English/Italian) books.

Also have the finest automotive history periodical, 196 issues of Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 1 – 49, plus Indexes for Vol. 21- 40, and the AQ Planner. I just need a good home and a fair return on these. ParamourDesign@comcast.net

Mac was one of the very best instructors at ACCD, and would always do what ever he could to help the students!

Like many other ACCD students and grads I enjoyed many hours talking about design with Mac both as a student and then in later years working as an Industrial Designer. His personality and honesty made conversations with him both a joy and a learning event.

It was a honor and joy to have known Mac; truly one of a kind that will always be missed. 🙂 DFO

No matter what the subject matter, it is always interesting to read an interview with a true intellectual. That’s what this is; it just happens to also intersect with a lifelong interest of mine. I rode a train to Washington DC to attend an interview/lecture with Irv Waaland, the chief designer of the B-2. It was very much like this. And I had just started to read Road and Track when his sports car design was on the cover..but I read his name across almost all the car magazines I read, from Rod And Custom to Car life to Sports Cars Illustrated. A big name, McMinn. A big name.

Four comments:

1) Best article that I have read about Mac and automobile design.

2) I was fortunate to have Mac as my senior year instructor (in a class of only myself). I essentially lived with him for three days a week for two trimesters. Though he appreciated presentation skills, he was more interested in teaching/challenging creative thinking. Everything I have learned about design came from him.

3) My relationship with Mac evolved into a close personal friendship that lasted to the end. He always made me feel that I was the most important person and friend in the room. What I have learned over the years is that Mac treated most of his students as friends in the same way. I continue to be struck by people who refer to him as friend. A more encouraging and positive person you will never meet. I never heard a negative word about anything from him.

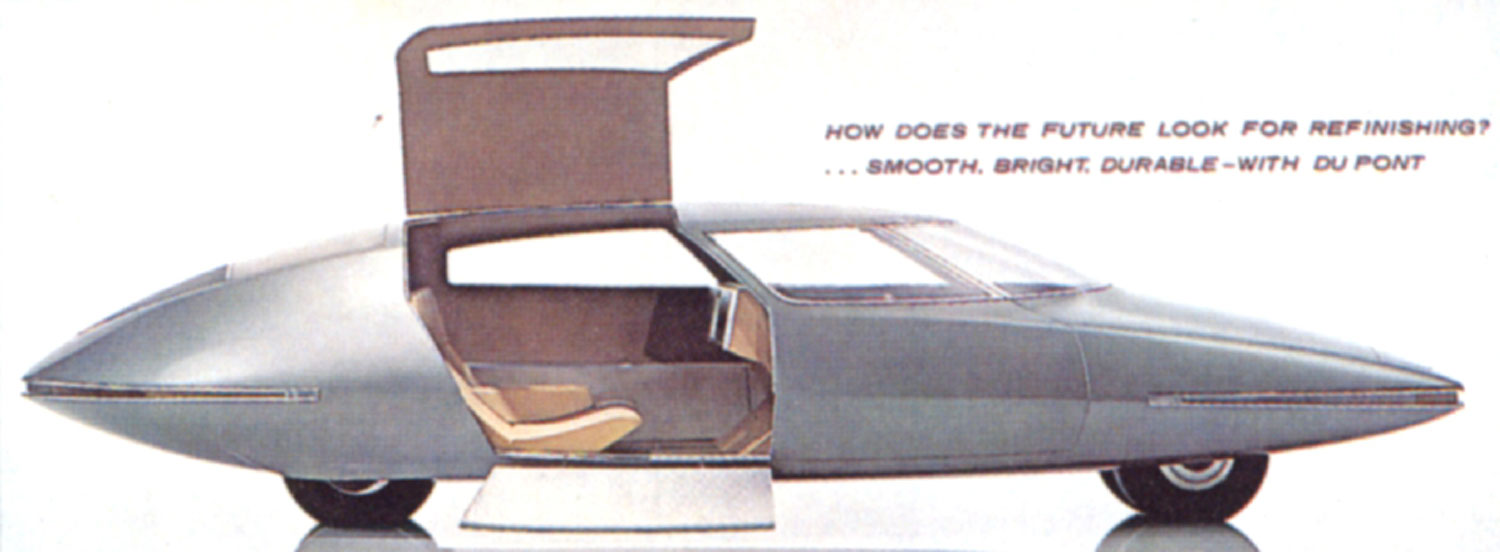

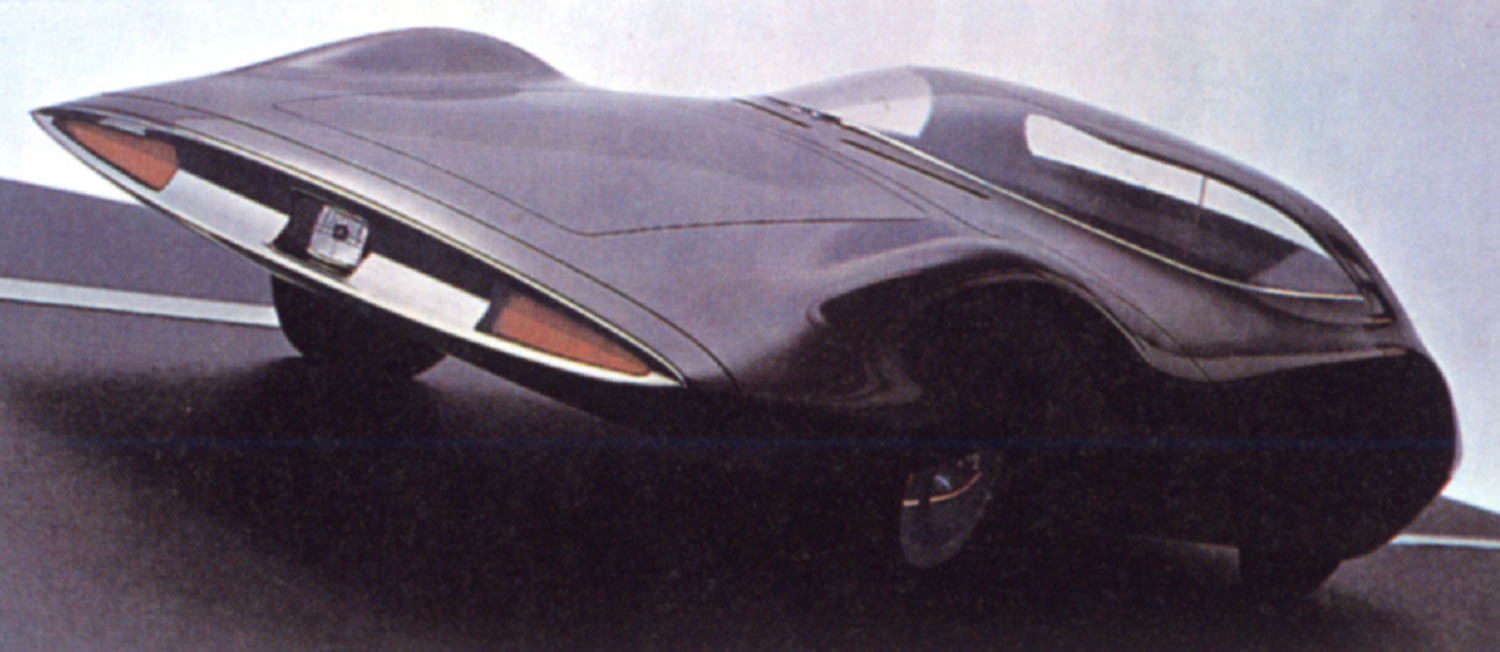

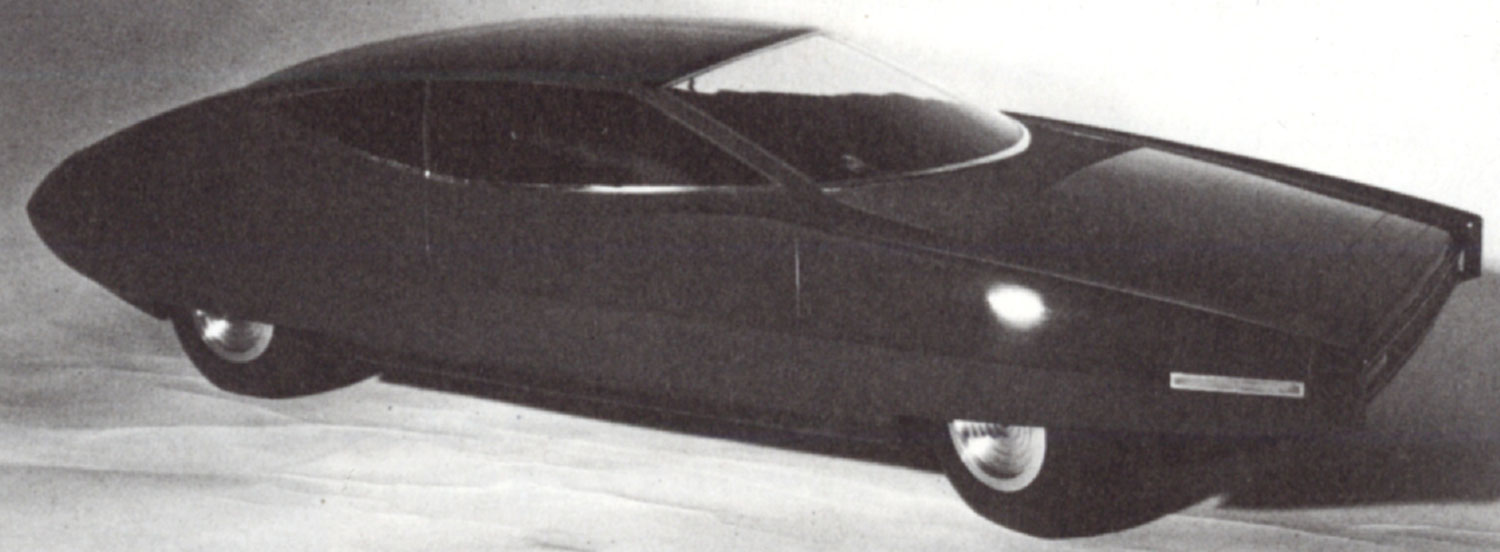

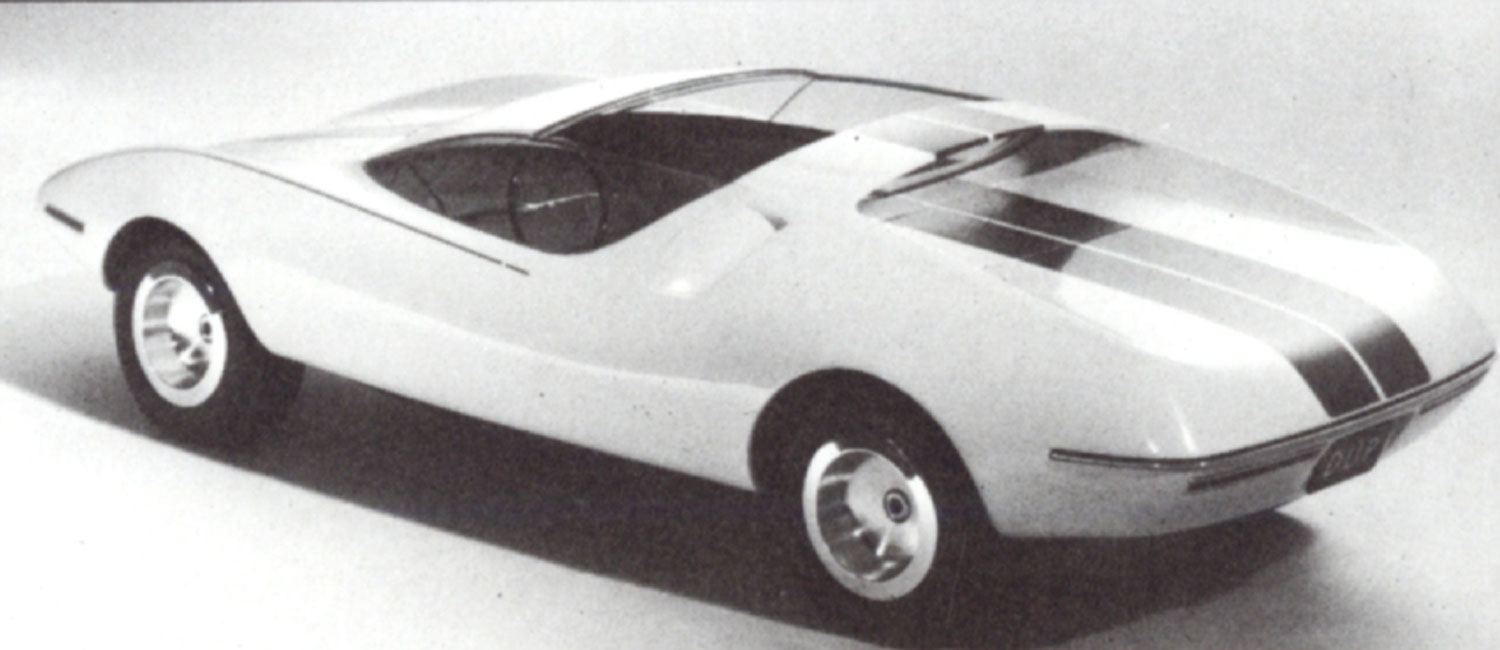

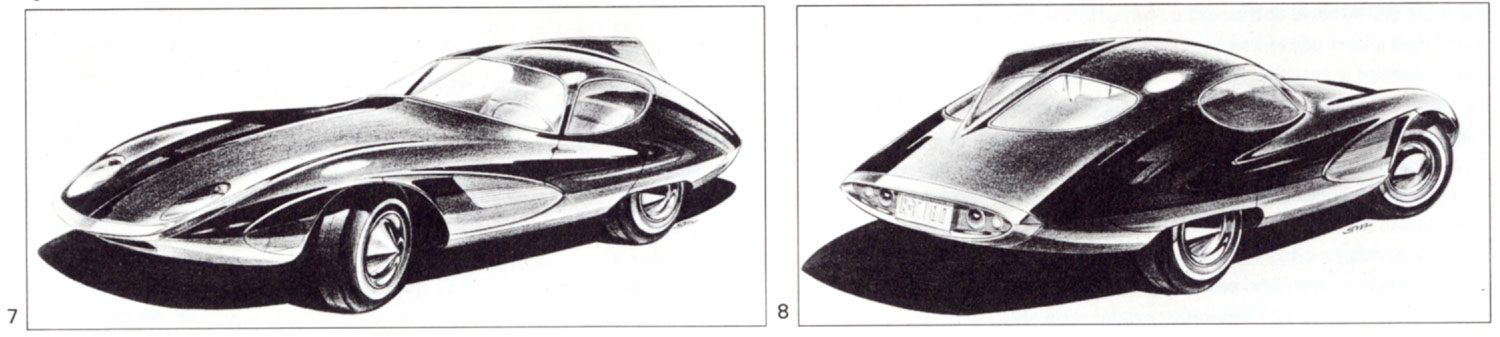

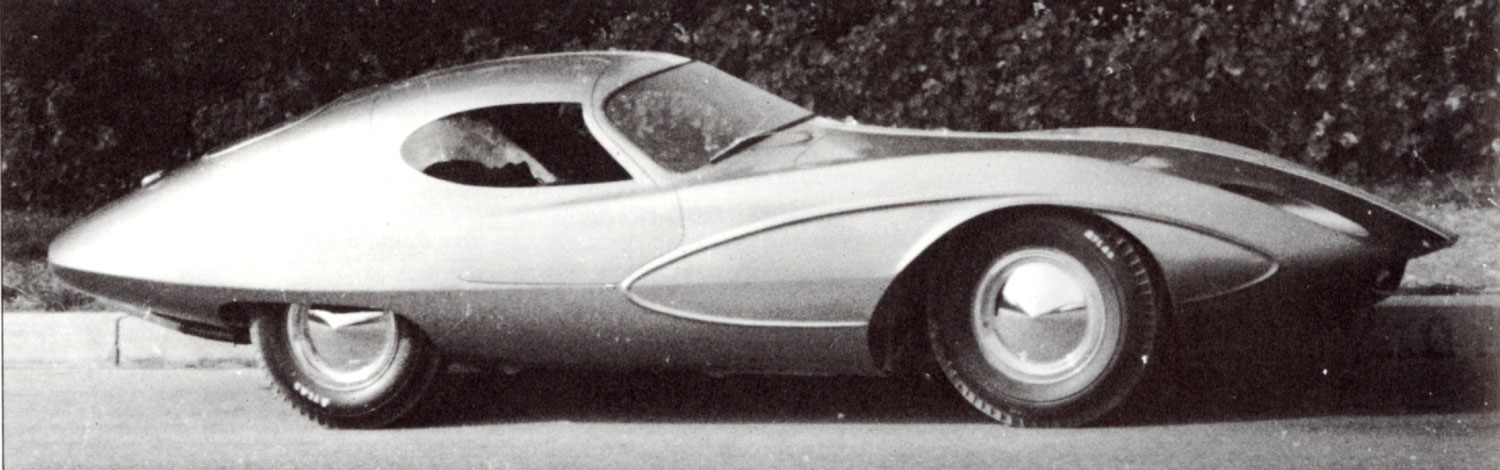

4) FYI, the DuPont models were built by mastercraftsman William Riethardt for Mac. I watched Bill build the models like he was assembling a fine watch.

Great article on Mac.I learned so much about him as well as what I and other designers experienced when we were young, especially those of us from small towns with no exposure to design.. He was a good teacher and one of the assignments was to collaborate with another designer- a good prelude to working in a company. After working at GM, I visited ACS and had lunch with Mac and Buehrig. I was nervous about saying something stupid, but they were great and I was glad to be included. thanks for this great article.