Ford’s X-100 (aka Continental 195X)

By Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Bob Gregorie’s last day at Ford was December 15, 1946. As head of the Ford Design Department for the past 11 years, he had been unable to convince Henry Ford II or Ernie Breech, Ford’s new executive vice president, that Ford designers should continue designing vehicles based on collaboration between Gregorie and anybody but Breech—and not under the GM committee system imposed by Breech.

When Breech hired Walker to design a proposal for the ‘49 Ford, he promised him a long-term consultancy at Ford if his proposal was chosen over Gregorie’s. After Walker’s proposal won and Gregorie chose to retire, Breech changed his mind. He decided it was more important for Ford to rebuild its own design department. As a result, Walker, and his employees, including Joe Oros and Elwood Engel, left.

Things didn’t work out quite like Breech had planned. Ford hired a bunch of new designers, many from GM, by paying them more money—sometimes twice their present salaries, and with promises of quick promotions as Ford rebuilt its design department. Designers hired from GM included Gene Bordinat, Bob Maguire, Don DeLaRossa and Dave Ash, who all eventually became at least studio heads at Ford. Another designer hired from GM was George Snyder, who soon became chief designer at Ford. To make a long story short, Snyder didn’t work out. He felt that Ford designers and clay modelers who had not previously worked at GM were inferior and needed to be weeded out. He got rid of many old Ford design employees. He was ultimately told to stop it, but didn’t, and that led to his own termination. Dissension continued because the design proposals from Ford’s new designers began to look too much like they came from GM. Breech’s solution was to bring back Walker and his employees, especially Oros and Engel, who had successfully built the fresh and distinctive looking full-sized ‘49 Ford clay model.

By 1949, Walker, Oros and Engel were back at Ford, but not as Ford employees. Walker drove a hard bargain before he agreed to return. He was permitted to maintain his own design business plus a side business run by his son that sold trim parts to many automobile companies. Walker also demanded and got control of all publicity about or from the Ford Design Department. As a consultant, Walker worked part-time, and Oros and Engel continued to work for him, although they were assigned to the Ford design department full-time. Engel was Walker’s assistant manager and was also assigned to the Lincoln-Mercury studio. Oros was assigned to the Ford studio, and if he (or Walker) didn’t like the designs Ford designers were proposing, he was authorized to design and build his own proposals in competition with those from Ford designers. As might be imagined, this arrangement did not make Walker, Oros or Engel many friends at Ford design, but it was not changed until 1955.

Oros soon discovered that many of the new designs coming from Ford designers looked like they were from GM. His solution came in the form of two recommendations he made to solve the problem. His first recommendation was that the Mercury and Lincoln designed for 1952 had to show a distinct design similarity with his design that had been chosen for the ‘52 Ford. (Oros’ ‘52 Ford design beat out one from Bob Maguire that did look like it came from GM.)

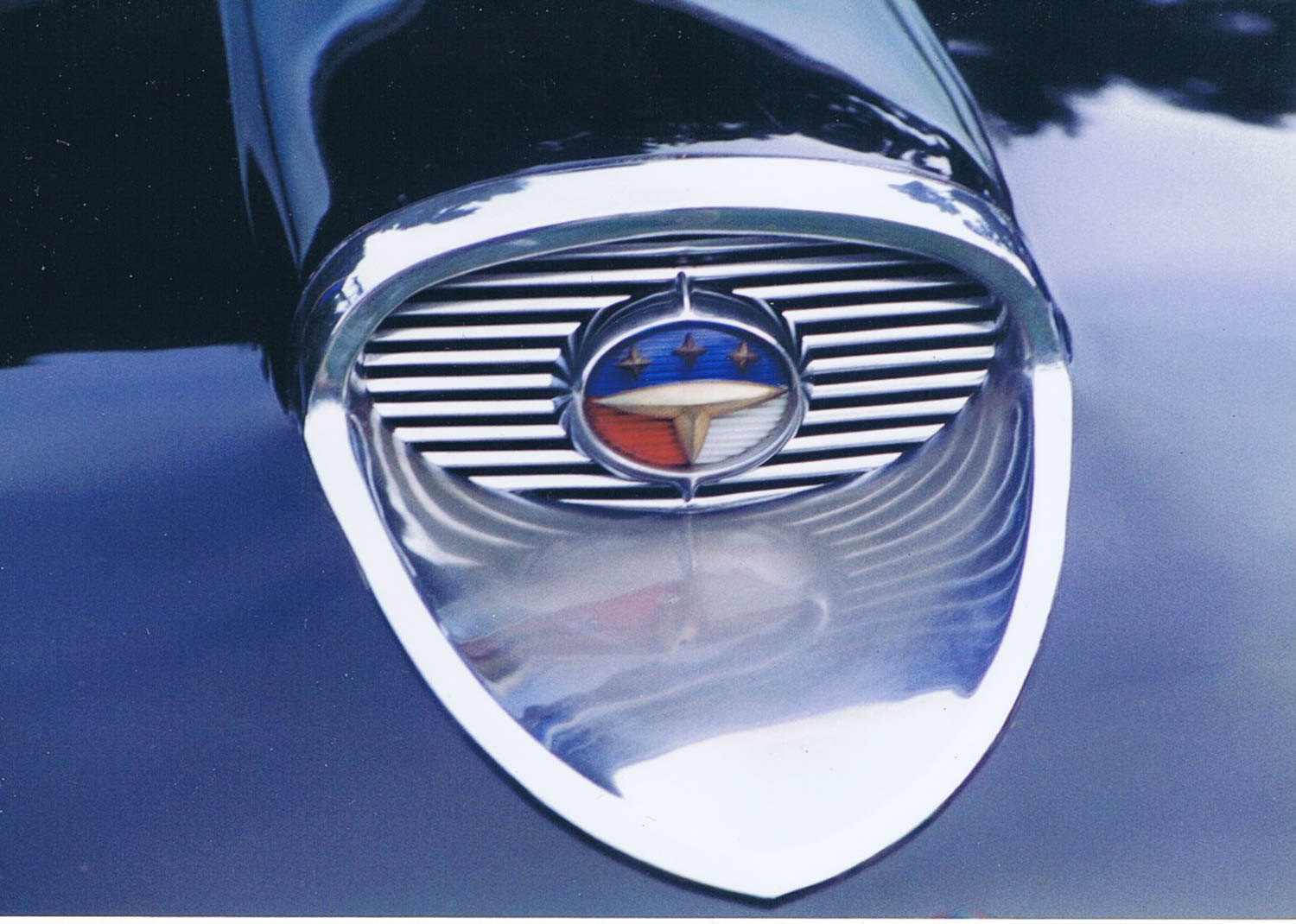

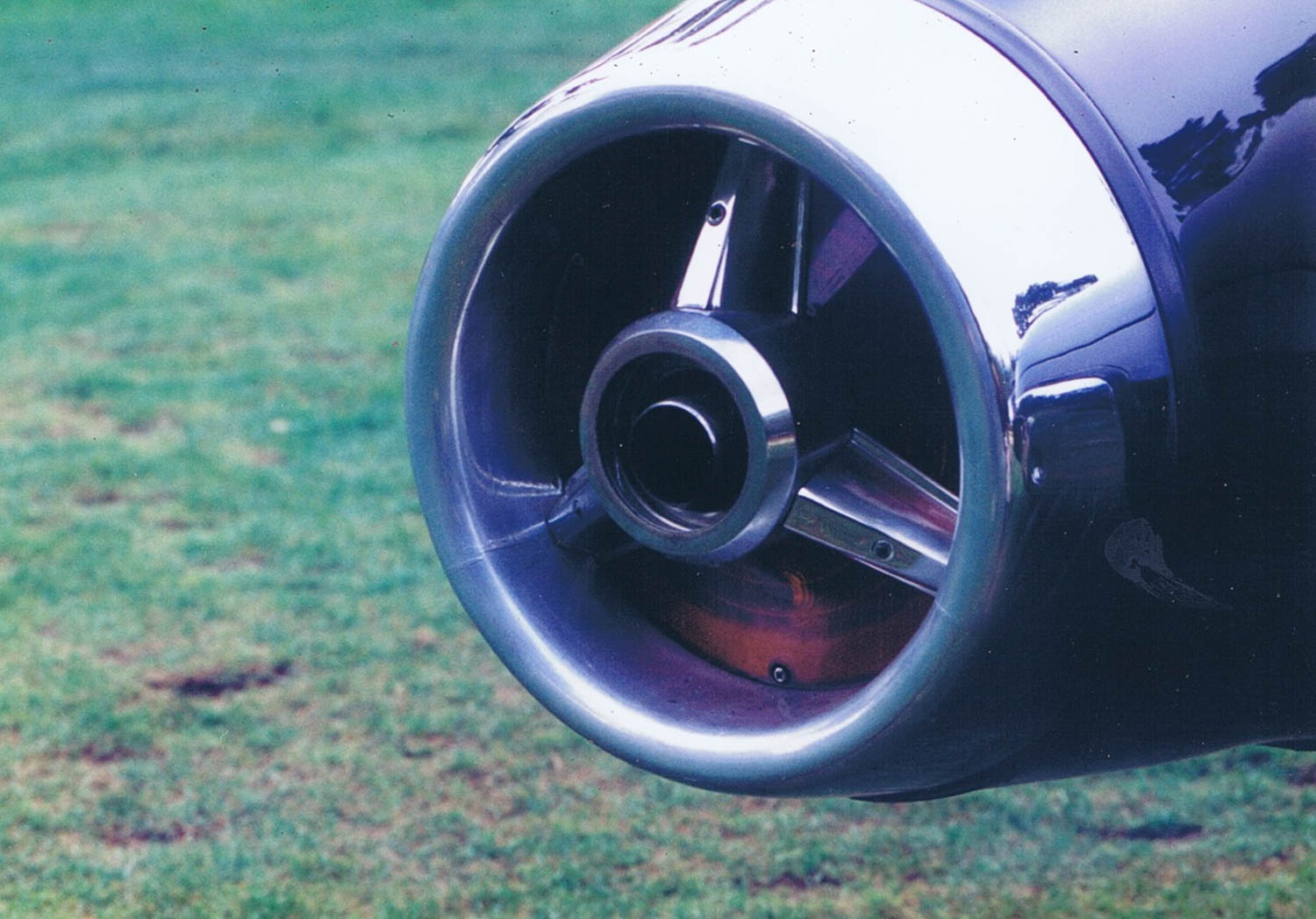

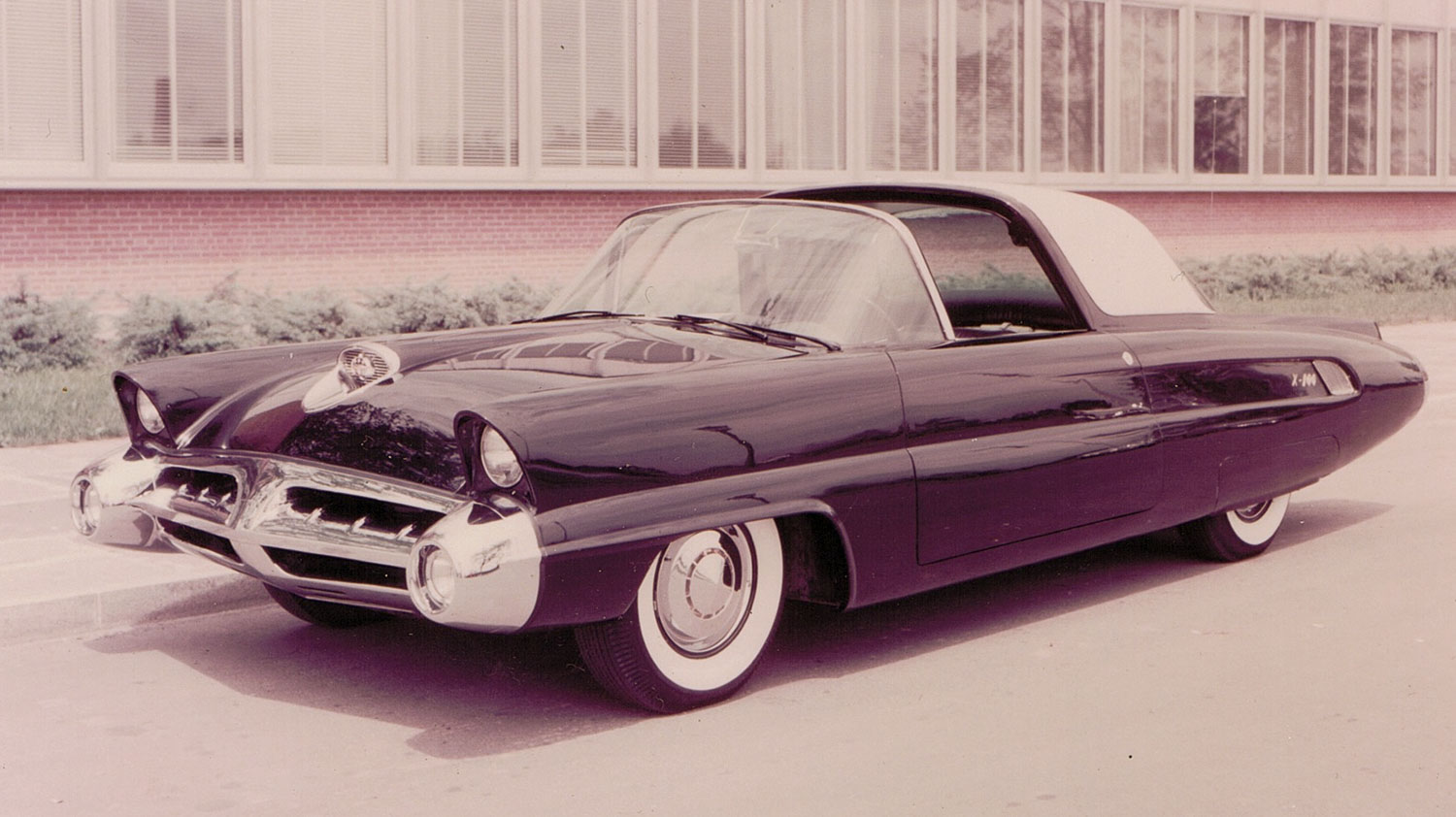

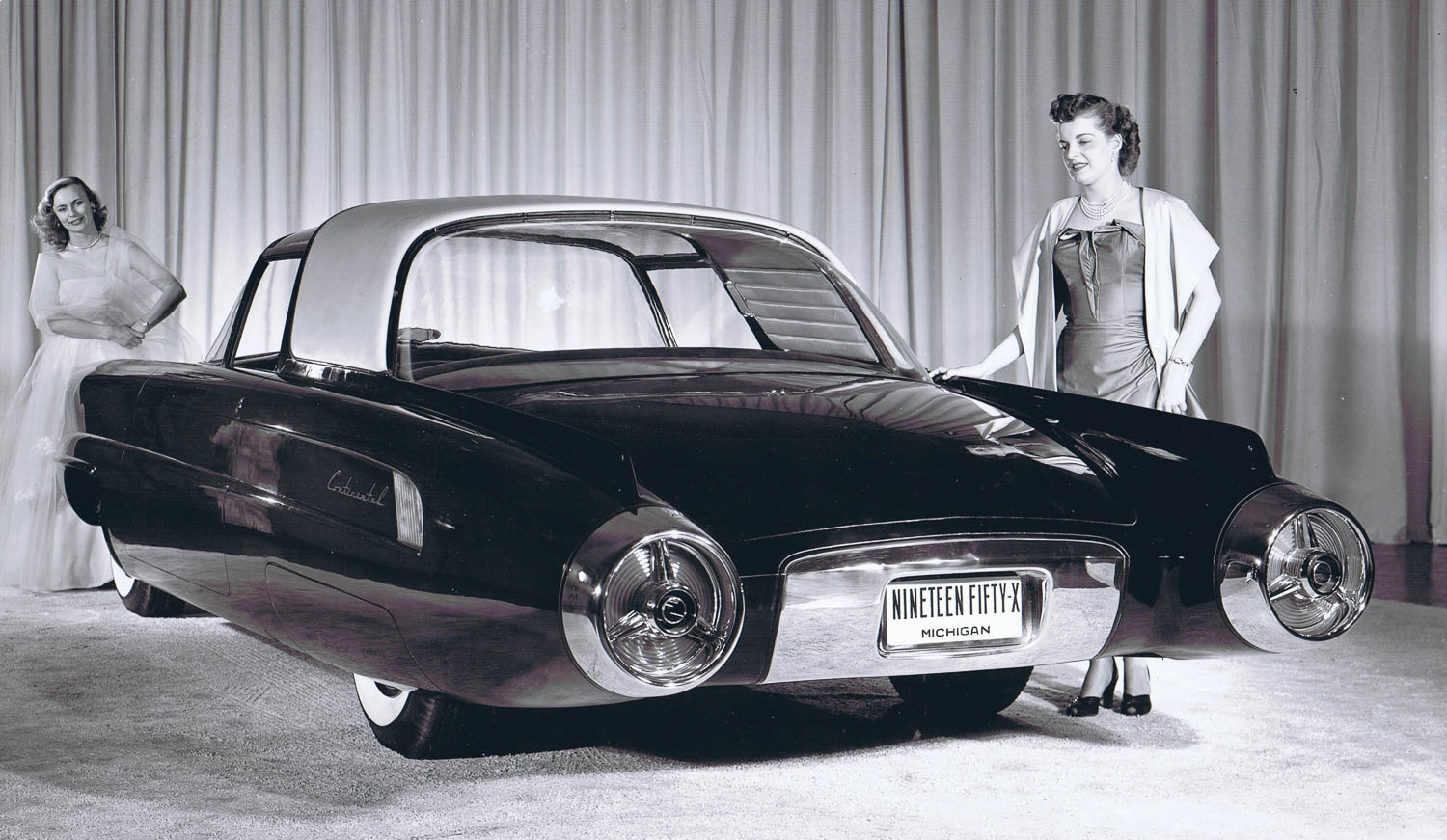

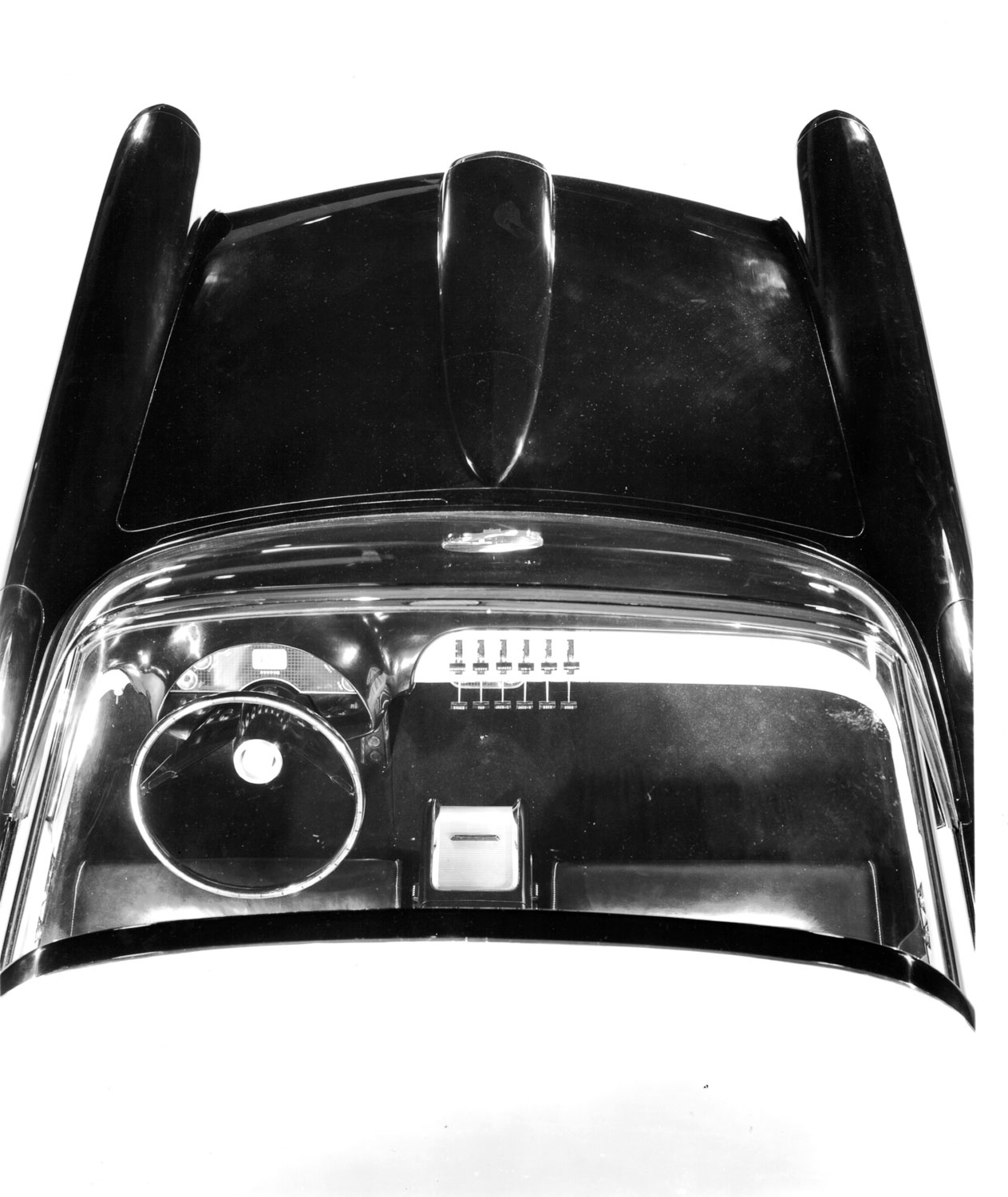

Oros’ second recommendation was to build a new Ford concept car to match two concept cars then being designed and built at GM (Buick LeSabre and Buick XP-300). Oros meant his new concept car to capture features he thought were important for future Fords—like big, round taillights. Walker got approval for Oros’ new concept car which was actually designed and built in the Lincoln-Mercury studio starting in late 1949. Oros’ concept car was based on several of the 3/8-sized model concept cars designed in Gil Spear’s Ford Advanced studio, but the X-100 was heavily modified during the design process. No scale drawings or clay models were made before the full-sized clay model was designed and built. The big round taillights on the X-100 were actually based on one of Spear’s 3/8-sized models called the Cutlass. Oros acknowledged that he, Engel and Spear collaborated often on the design of the X-100, but otherwise he and clay modelers Charlie and Leonard Stobar were mostly responsible for the exterior design of the X-100. Maguire, Ted Hobbs and Herman Brunn designed the interior, John Najjar designed the instrument panel, and Dave Ash supervised the building of the full-sized clay model.

Word of a fantastic concept car being designed at the Ford Design Department soon spread resulting in Ford executives dropping by to see the X-100. Soon Henry Ford II also came to see it, and he spent the better part of an hour examining it and asking questions of Oros. After that, HFII decided he had found his new Continental, and the name of the car was changed from the X-100 to the 195X Continental.

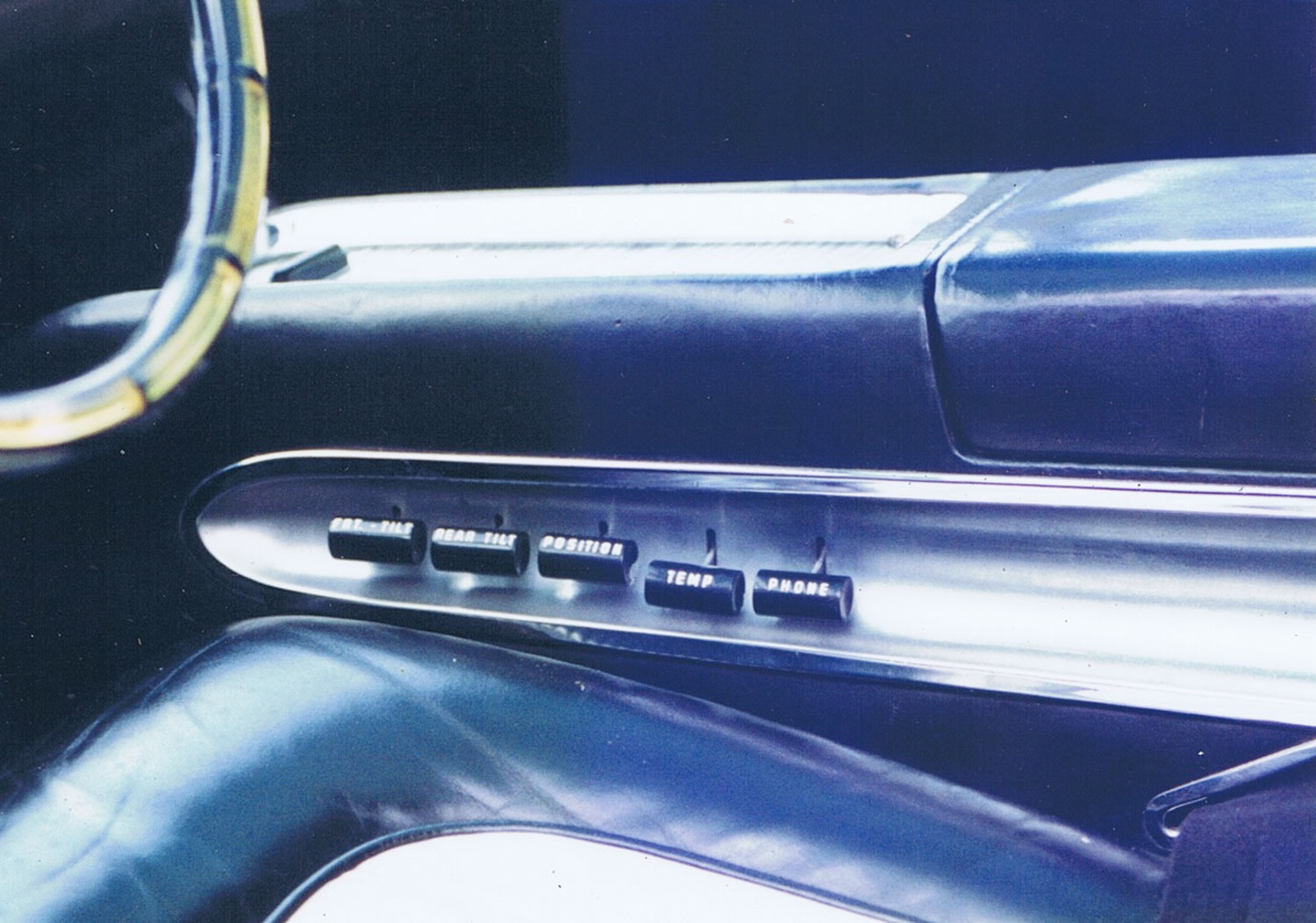

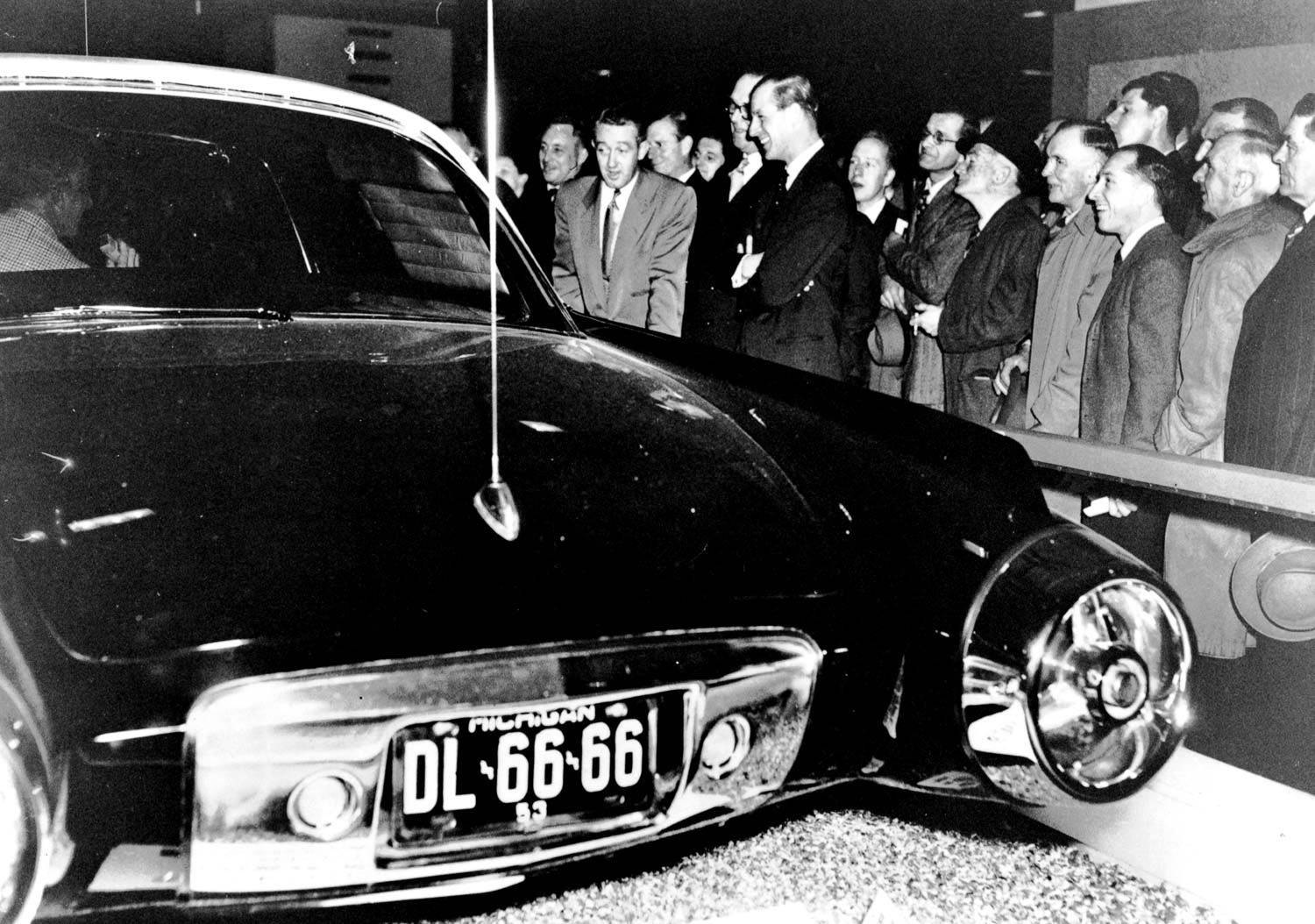

Meanwhile, in 1951, younger brother Bill Ford was given the job of producing a new Continental, and by June 1952, studies he had commissioned recommended the new Continental be a “modern formal” design—and nothing like the 195X Continental. Thus the name was changed back to the Ford X-100. In the meantime, Ford‘s Experimental Engineering department was building the X-100 as an operable metal-bodied car with as many future features (including a modified ‘52 Lincoln chassis, a five-carburetor Lincoln engine, a prototype ‘55 Lincoln automatic transmission, and a de Dion rear end) together with all the gadgets engineers potentially saw in Ford’s future. According to Ford engineers who worked on the X-100, the cost to build it as an operable automobile with all its gadgets was in excess of $200,000.

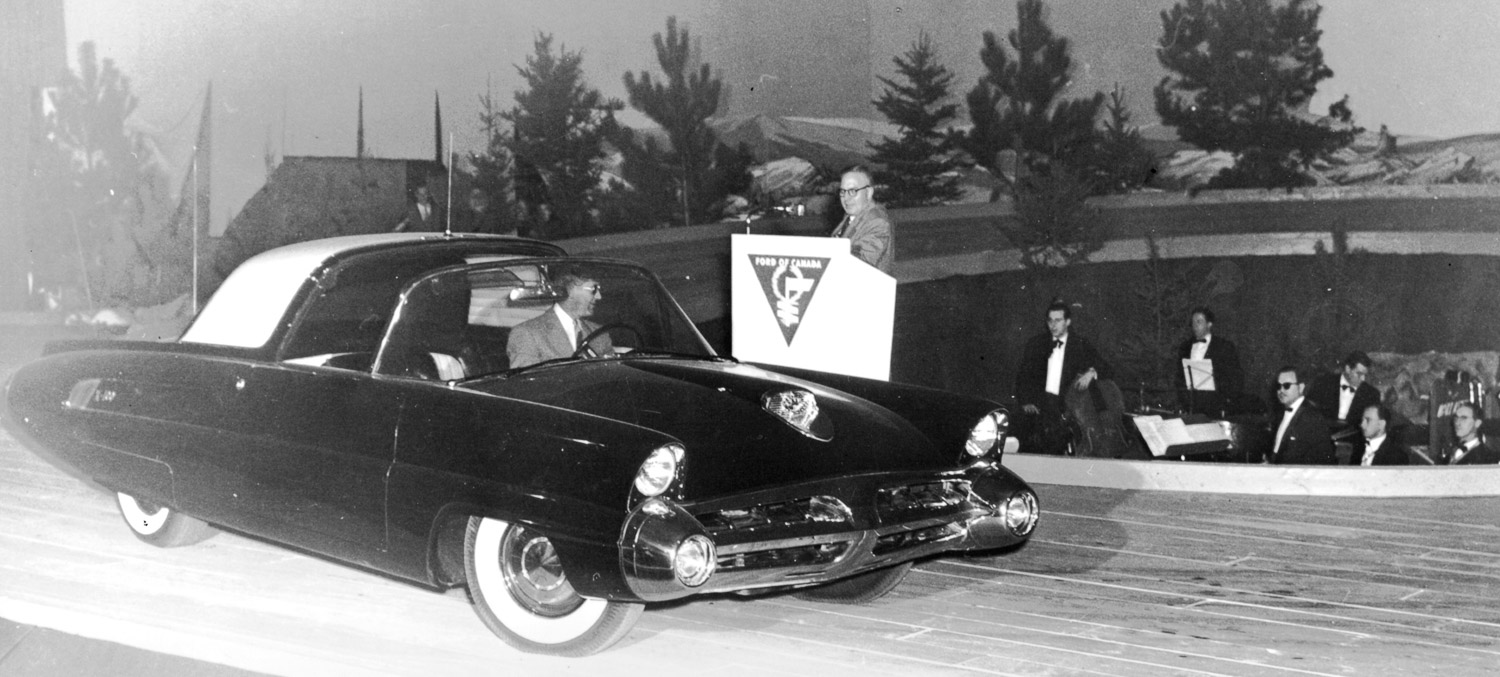

In January 1952, even while the operable X-100/Continental 195X was being built, a fiberglass and plaster full-sized model of the Continental 195X was unveiled to the public. On June 15, 1953 the running X-100 (by then the name had been changed) was re-introduced on a national TV show celebrating Ford’s 50th anniversary. The X-100 was then driven on the Ford test track at speeds up to 90 mph, and for several weeks HFII drove the X-100 to work and around Dearborn. Then, the X-100 was shipped to Europe, where it was driven and displayed from city to city. Back in the United States, the X-100 was driven to appearances all across the U.S. and Canada. It also starred in a major Hollywood movie called “Woman’s World.” After that, the X-100 was driven from Ford dealer to Ford dealer across the US where it was displayed in their showrooms. Surprisingly, rare but necessary repairs (blown condenser, body damage, etc.) were usually made while it was on the road at local Ford dealers.

No longer one of the new Ford concept cars, by August 1958, the X-100, showing an odometer reading of 33,192 miles, was given to the Henry Ford Museum, where it is now displayed when not on loan to events such as the Pebble Beach or Meadow Brook Concours.

Design features on the X-100 have been incorporated on more Fords, Mercurys and Lincolns than from other concept cars. The X-100 is easily Ford’s most important concept car—and it was distinctly a Ford product.

Photos: Ford Design

Books by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

Ford Design Department—

Concepts & Showcars

1999, 10×13, 400 pages, Fully indexed

900 photos. Includes 150+ designers and sculptors, and highlights 100 concept cars.

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Lincoln Design Heritage:

Zephyr to LS (1936-2000)

2021, 10×13, 480 Pages, Fully Indexed

1,600 photos and illustrations

ISBN 978-0-9672428-1-1

The Ford book is $50 plus $7 S&H (US). The Lincoln book is $85 plus $10 S&H (US). Both books bought together are $110 plus $17 S&H (US). To order, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

Great story and photos, Farrells. Well done!

I have always liked this car, and I remember seeing it in the movie back then!. I thought it influenced the ’61 Thunderbird also, another all-Ford design I really liked. Interesting story. Thanks.

Hi Dean. What happened to my comment?

I don’t know. Please re-submit.—Gary

I seldom say this, but wow. Wow. This car still exists? Where can we see it?