Ed Welburn and the Oldsmobile Aerotech—A designer’s fairytale.

Interview and adaptation: David Rodríguez Sánchez

Images: General Motors, David Reeves, Ed Welburn

This is the third Dean’s Garage post about the Aerotech. Check out the other two for more information about the project, including videos: 1987 Oldsmobile Aerotech (10/2011), and Oldsmobile Aerotech Interior Design featuring William Quan (11/2011)

Welburn: “In the early days of the automobile industry all cars were created by engineers, draftsmen, and craftsmen and car design schools were non-existent. General Motors was the first car company to create an in-house design organization, and they hired Harley Earl to run it. Mr. Earl hired people who were great artists and passionate about cars. They were assigned to his in-house school where Mr. Earl trained them to be car designers. Some were then assigned to the GM design studios, and some were let go. Many went on to lead design studios at other companies. This in-house school at GM was known as Design Development or ‘The School’, and it existed until 1972, when more and more design schools were developing transportation design programs.”

Ed Welburn grew up in suburban Philadelphia. At the age of eight, a motor show was held in the city. This sealed his fate. At 11 he sent his first letter to GM; he was replied and told about the steps to follow towards his dream.

Welburn: “I first got my foot in the door at GM Design in 1971. I was fortunate to be a part of a ten-week long GM’s summer internship program. I did not attend a design college with a major in car design before, but I studied product design, sculpture, and painting at Howard University’s School in Washington D. C. They liked my work so much as an intern that they wanted me to simply complete my senior year at Howard University, and they would hire me. This happened on September 2, 1972. At the time, my student portfolio was very much inspired by the Chaparral 2H, with its sleek profile and windows on its side. I created a series of sketches of production sports cars based on that theme. I was assigned to Design Development, the studio for new hires and I may have been the last GM designer to have gone through the old ‘school’. After a month in that orientation studio, I began a one year rotation through three types of studios to see where I fit best, spending three months in each of the three studios. The first studio was Advanced Chevrolet where they were working on concepts for future Chevy sedans. Second was the production Pontiac studio where I contributed sketches for Pontiac Grand Prix, but in general given small assignments like designing a tail lamp for the 1974 Pontiac Grandville, my first production contribution. The third stop was Advanced Buick where they were working on concepts of a future Riviera for Bill Mitchell. In that first year I was way over my head. The designers around me were really good and I had so much to learn.

“At the end of that first year I was assigned to the Buick Production Studio because of my great fit with designing advanced Riviera concepts. I spent two years in the Buick studio, contributing to the designs of the 1977 Buick Electra, 1977 Riviera, and 1979 Riviera. Then I was assigned to the Oldsmobile Studio where I worked for 20 years. I worked my way up from entry level designer to studio chief designer in Oldsmobile.

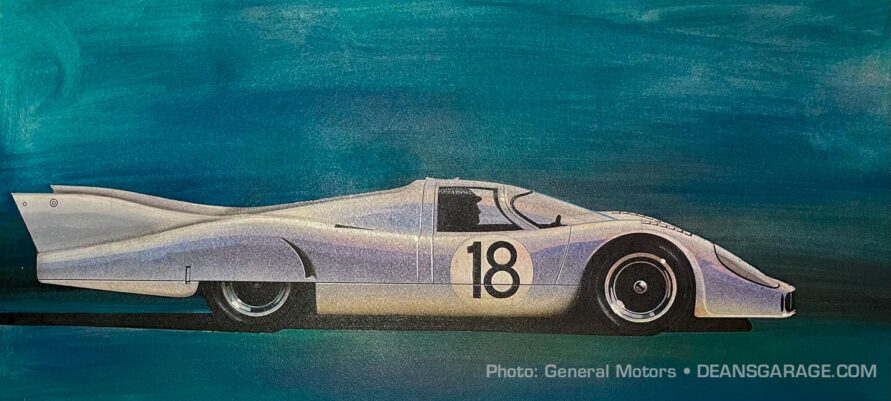

I loved what I was doing, but, as said, I also had a passion for race cars, in particular cars which raced at Le Mans. The Porsche 917 long tail was a favorite and in my spare time I would sketch that type of thing, leaving a nice stack of those sketches on the corner of my drawing table.

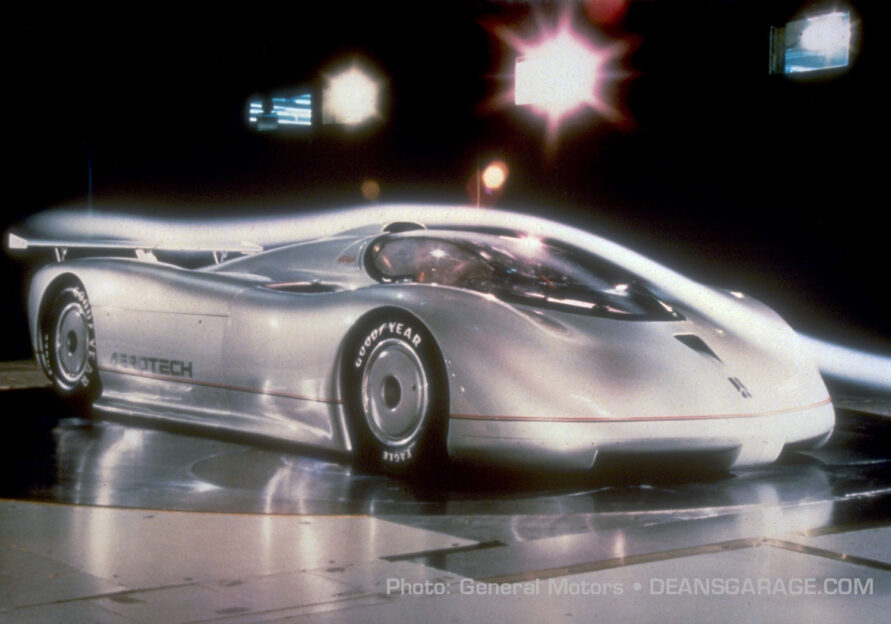

“A rumor began to circulate that one of GM Designs very confidential advanced design studios was working with GM aerodynamicists and Oldsmobile engineers on a very secretive high speed research vehicle. The car they were developing was a super low drag shape, much like the streamliners you might see at Bonneville.

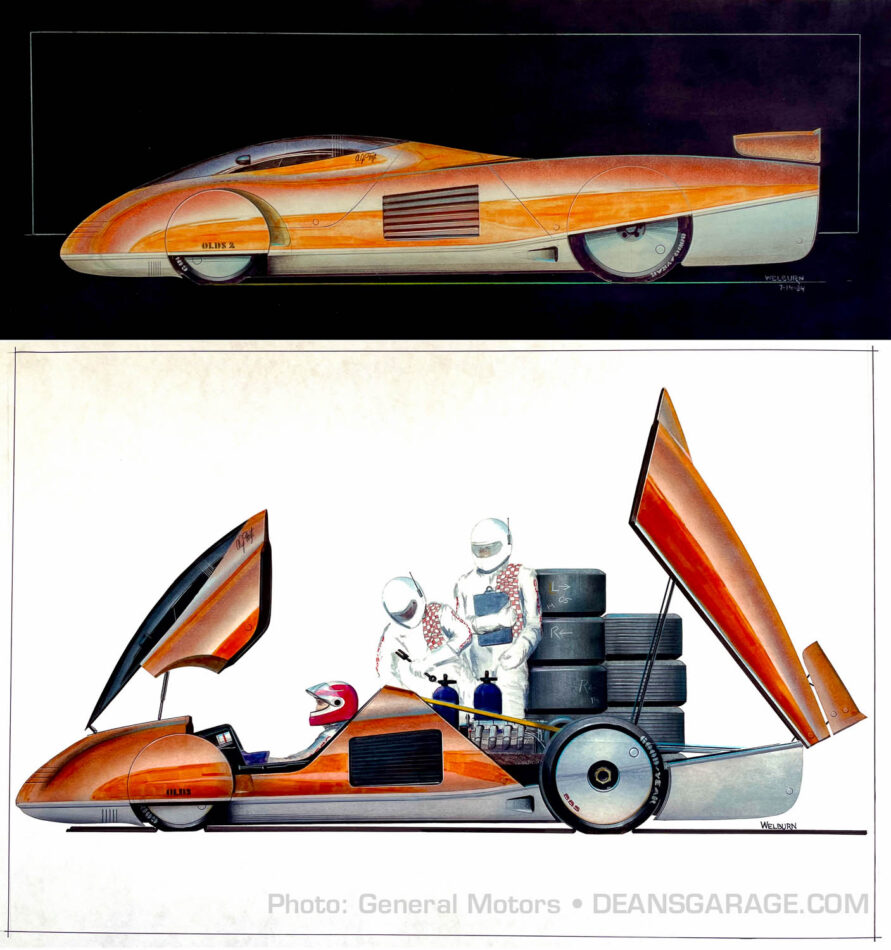

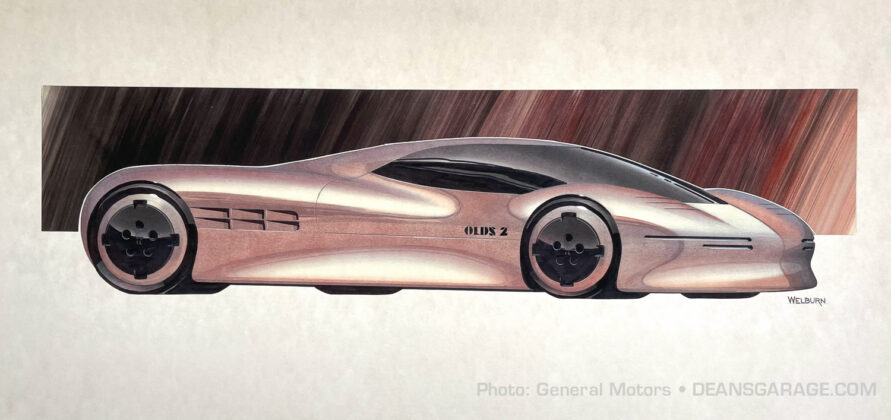

“One summer day, Len Casillo, executive design director in charge of Oldsmobile and Buick studios, stopped by my drawing desk. He had remembered seeing my Le Mans-inspired sketches on my desk and asked me to create some sketches for the secret Oldsmobile research vehicle. I was super busy working on the program to create an all new 1988 Cutlass Supreme, but I jumped at the chance to sketch on this research vehicle. I had a plan to create a series of drawings, but Casillo returned to my desk just as I completed my very first one. The sketch—dated July 14, 1984—was done in Foyt’s Coyote Orange and its wheels were skirted to reduce drag. I cautioned Casillo that I had many other ideas yet to be drawn, but he raced off with sketch number one! Apparently, all was not well with the Olds research project and a new design was urgently needed.

“Design leadership loved my sketch and wanted me to quickly develop a scale model before the Oldsmobile leadership team and A.J. Foyt came to GM Design for their meeting on the project. When they came, the original streamliner model was displayed in the conference room for their meeting. My completed scale model was not. When Foyt saw the streamliner he was concerned or, OK, angry, and so were the Olds leaders. They were then shown my scale model and the reaction was over the moon. Foyt thought that the Advanced Studios streamliner was just a test bed for my very sculpted supercar.

“At that point I was still not assigned to the project, but the next day Len Casillo came to my desk in Oldsmobile studio. His comment was: ‘How would you like to work on a high-speed research vehicle with 1,000 hp, a March Indy car chassis, and A.J. Foyt as its driver?’ Of special note, I was a mid-level designer at that time. I was not an executive designer at all. There were three levels of executive designers above me. It was very unusual, even unique that I was given so much authority to lead Aerotech from a design perspective. That said, I always kept my bosses informed of what I was doing with regular reviews.”

At the time, the world’s closed course record had changed hands many times. 1970 Buddy Baker’s Dodge Daytona held it initially, hitting the 200mph barrier around Talladega’s Superspeedway in Alabama. Foyt’s Coyote took it in 1974 doing 218 mph, with Mark Donohue averaging 221 mph in 1975 with his Porsche 917/30, 1230 hp Can Am monster; both of them, again, at Talladega. Foyt promised then to take it back someday. Mercedes C111 IV was the immediate predecessor to Aerotech’s, with test engineer Hans Liebold driving to a new speed record of 251 mph on the Nardò, Lecce circuit in Italy in 1979.

“Olds thought it would be a great way of promoting their new four cylinder engine by the name Quad 4. Ted Louckes, the very powerful chief engineer for Oldsmobile, had gotten that position only a little time before. It was his vision to create a vehicle that would exploit the capability of their newly created four-cylinder engine and I consider Ted to be the godfather of the project.

“Along with the car itself, I designed the crew uniforms, Foyt’s driving suit, the transporter for Aerotech, graphics, etc. My day job was designing Cutlass Supreme, Ceira, and Calais, though. As well as the Pace Cars for the Indy 500 in 1985 and, later on, 1988. My automobile artwork always began with very rough sketches and then the final rendering was created. The entire process took about eight hours.

“The working relationship between the design studio and engineering was quite formal. Bill Porterfield was the Oldsmobile engineer who managed the Aerotech project. I believe that the name ‘Aerotech’ came from the Oldsmobile marketing department. There were two Oldsmobile exterior design studios at the time: Olds 1 did the Olds 98, 88, and Toronado and Olds 2, where I worked, did all things Cutlass as well as the Aerotech record cars. Olds 1 did the subsequent Aerotech ll and lll mere show cars, which had nothing to do with the goals of the original Aerotech. This constituted only a desperate move from Oldsmobile to capitalize on our Aerotech name and achievements.

“There was an unpleasant rivalry between the two Olds studios. Bill Porterfield had to communicate with multiple suppliers for the Aerotech project: Olds 2 at GM Design, March Engineering, the two engine suppliers and their special advisors, Good Year, GM Aero Lab, GM Proving Grounds, Ft. Stockton track facilities , A.J. Foyt Jr., A.J. Foyt Enterprises, and countless others.

“The body and chassis were engineered at March Engineering in Bicester, England. Our studio worked very closely with GM Aero Labs so that we could get the most slippery shape possible. Max Schenkel was the aerodynamicist. He ran GM’s wind-tunnel at our Tech Center and had been a consultant for numerous race cars, too.”

According to Tino Belli, as much as for Aerotech itself, Schenkel was interested in the pros and cons of the different wind-tunnel testing methods, mainly to try and prove that the GM Aerolab was better than any other facility.

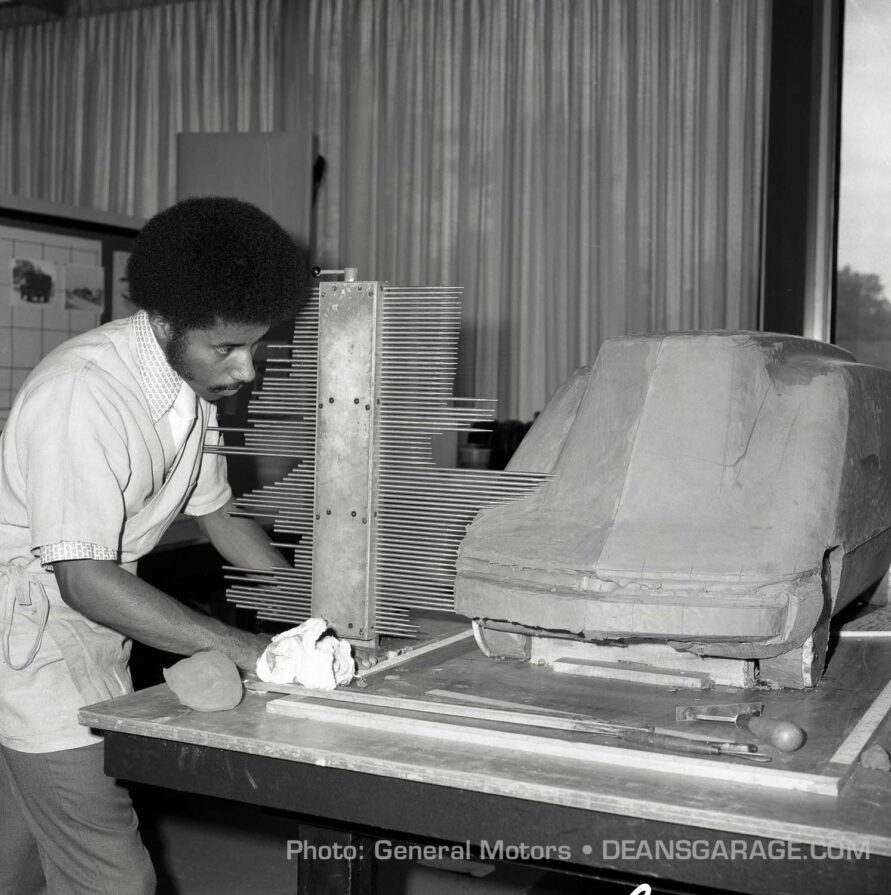

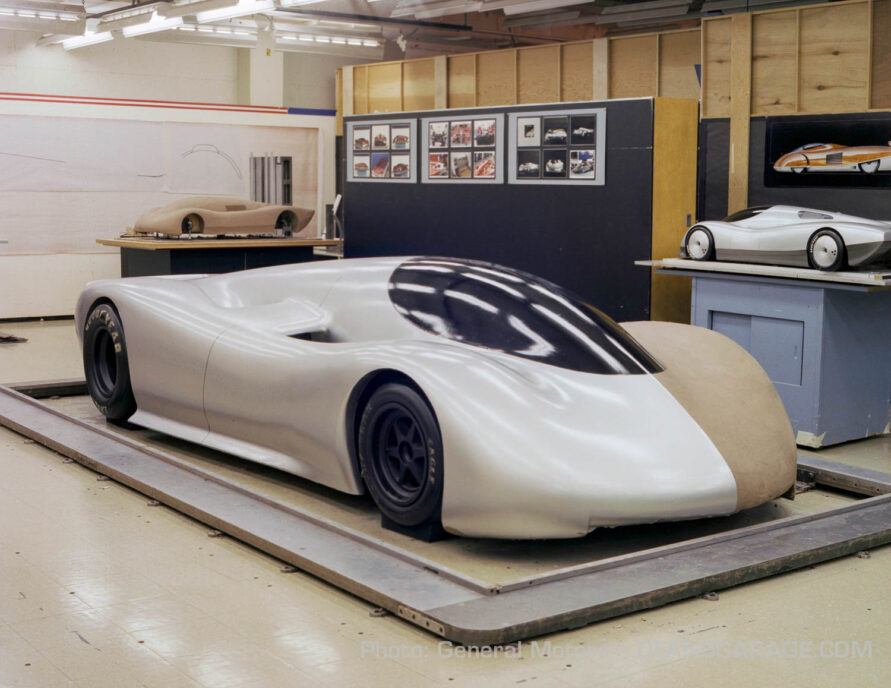

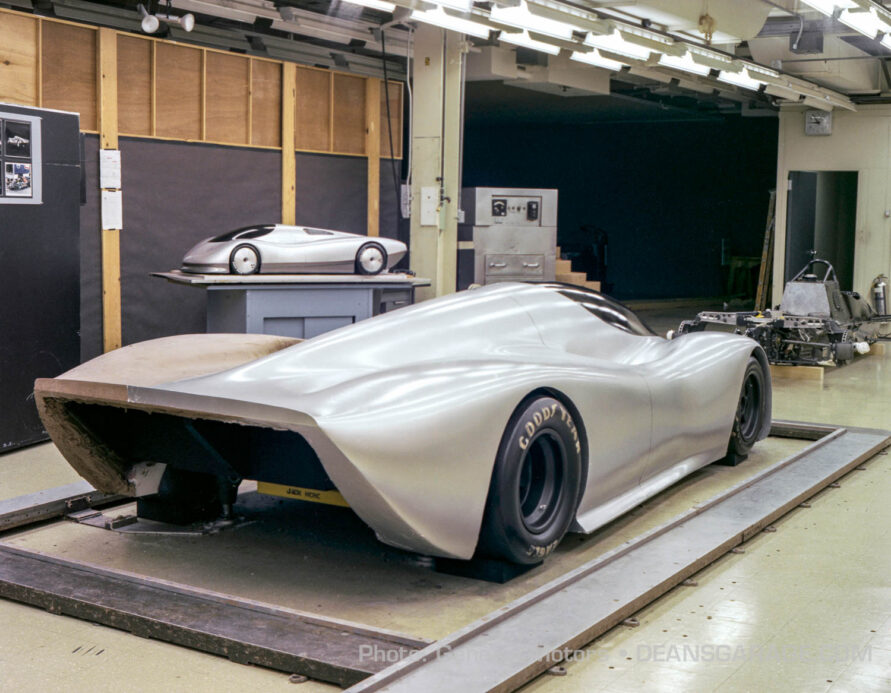

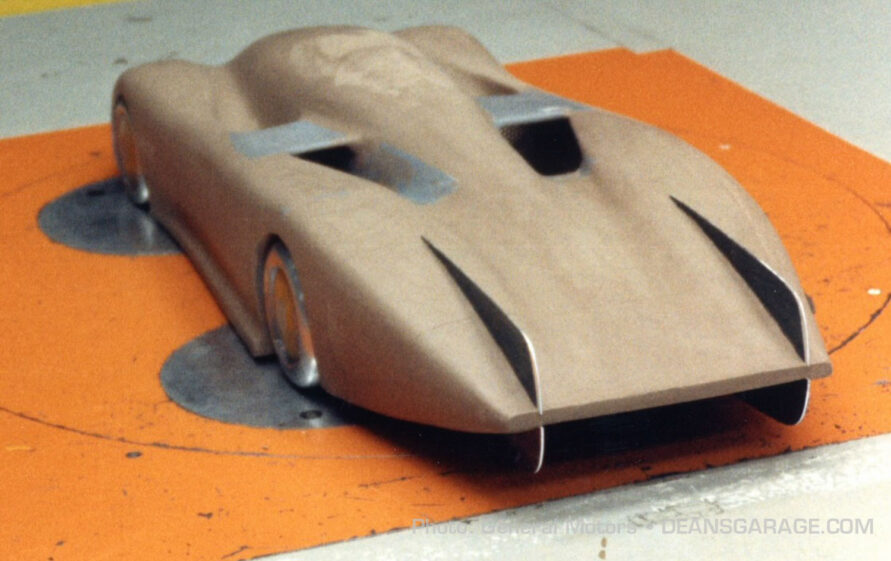

Welburn: “He also was the person who insisted on management to have the super-low drag long tail version. Most aerodynamicists are very difficult to work with, but Max was a dream. He was very knowledgeable about aero and understood the needs of Design. The process in the studio was to quickly move from sketches to a clay scale model and from that move just as quickly to the full size clay model. Kirk Jones, one of the most talented sculptors I ever worked with, was the lead sculptor.”

March received casts taken from GM’s clay model to define the Aerotech’s top body surfaces construction, but nothing yet was specified for the crucial underside.

Welburn: ”Though my first sketches were, as said, done in Coyote Orange, silver was generally used at Design to best evaluate the surface development of our clay models. It looked so good in silver that we stayed with it.”

At one point the scale model—while still representing Welburn’s very first idea—was painted metallic red, and later changed to silver.

Welburn: “The final design of Aerotech was silver in part to make it clear that Aerotech was a GM concept and not a ‘Foyt’ concept. Aerotech is wider than a conventional car, requiring us to execute the clay model in a location separate from the Oldsmobile studios. Executing the full size model in the basement of the Design building also gave us the benefit of added security, privacy, and a location much closer to the aero team.

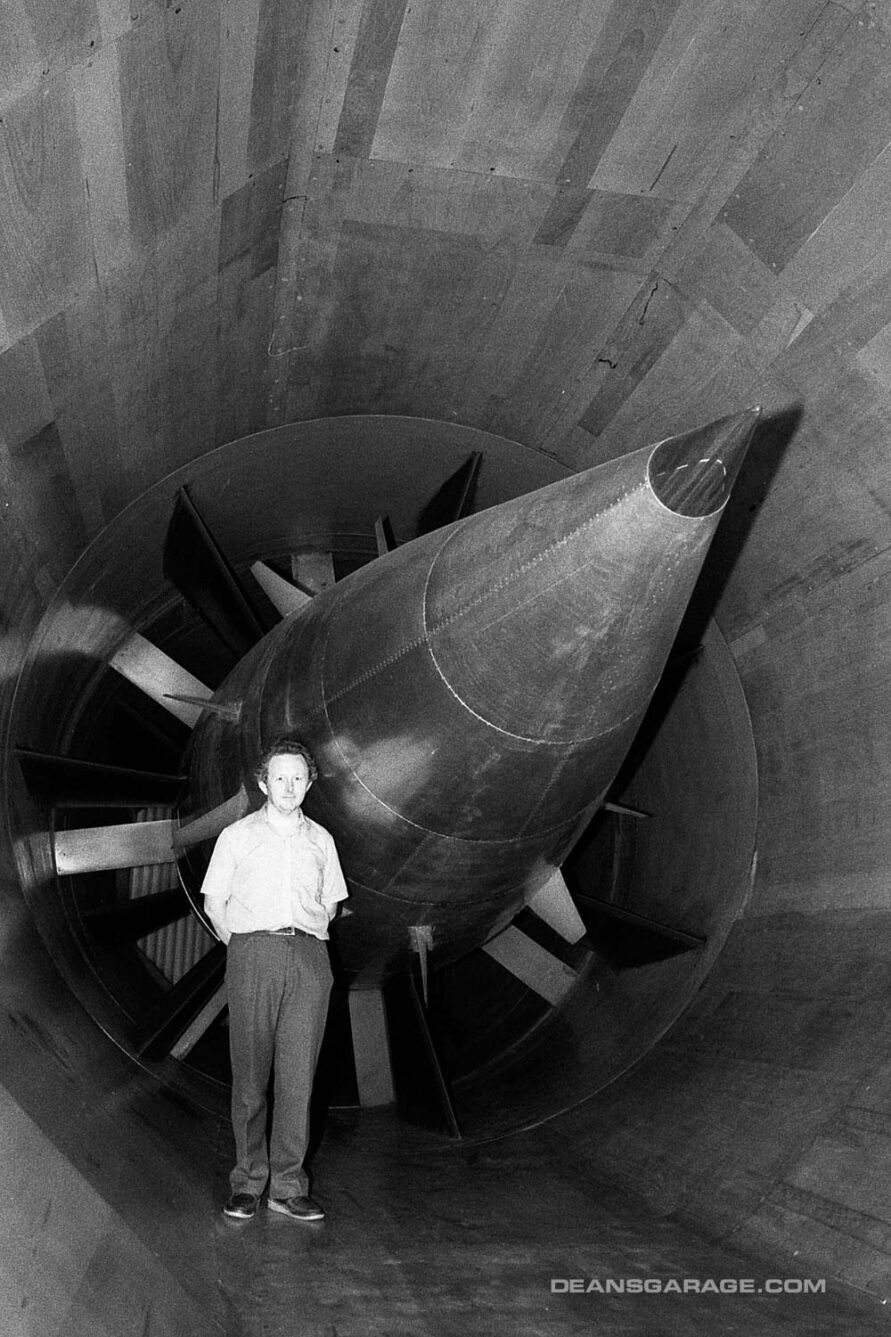

“Most of the aero development took place in the wind tunnel located next to the GM Design Center in Warren, Michigan. Testing was performed at night because of the added noise of the high speed requirements. We initially put Foyt’s Indy car in the tunnel, only to get a baseline. This car, in superspeedway configuration, had tremendous downforce due to its ground effects underbody and wings, front and rear, but being an open single-seater with exposed wheels and wings it had also a tremendous drag. The goal of Aerotech was to have comparable downforce for lapping Indianapolis, but without the drag. Aerotech did not have to conform to any rules, therefore its ground-effects tunnels were much larger than the Indy, F1, or even any Group C or IMSA cars of the day. With these large tunnels, no exterior wings were needed, therefore its drag was a fraction of the one of an Indy car, and THAT was one of the major reasons for Aerotech’s success. The later long-tail, streamliner car was even lower in drag.”

A key GM engineering objective was to compare rolling road wind tunnel tests used in motor racing and fixed ground plane, vogue at GM. March’s Brendan Gribben modellers team built a 25% scale model to test at Imperial college London’s rolling road facility. Tino Belli, nowadays Director of Aerodynamic development at Indycar, obtained his 1st class degree there. A member of March back then, Tino made refinements to the underbody, rear aerofoil, and radiator ducts. GM’s and March’s results were combined to finalize the design. More detailed aero tests were conducted in the GM tunnel afterwards. The full-size fiberglass model used was built on a March 84C chassis from the Gilmore-Foyt team old stock.

Welburn: “At the conclusion of this testing phase with the fiberglass model, I proposed that it was converted into a show car. That non-running show car was introduced at the 1987 Chicago Auto Show in February, along with Pontiac’s neat, new Pursuit concept-car, and then traveled the regular auto show circuit. The show car allowed the engineers and Foyt’s crew to focus on the running vehicles without interruption for shows and displays.”

The fiberglass show car, residing today at GM’s Heritage collection, was the only Aerotech in which the spectacular sci-fi looking interior designed on purpose for the Aerotech by William Quan was used. Quan, who had already designed the futuristic interiors of the 1983 Buick Questor concept.

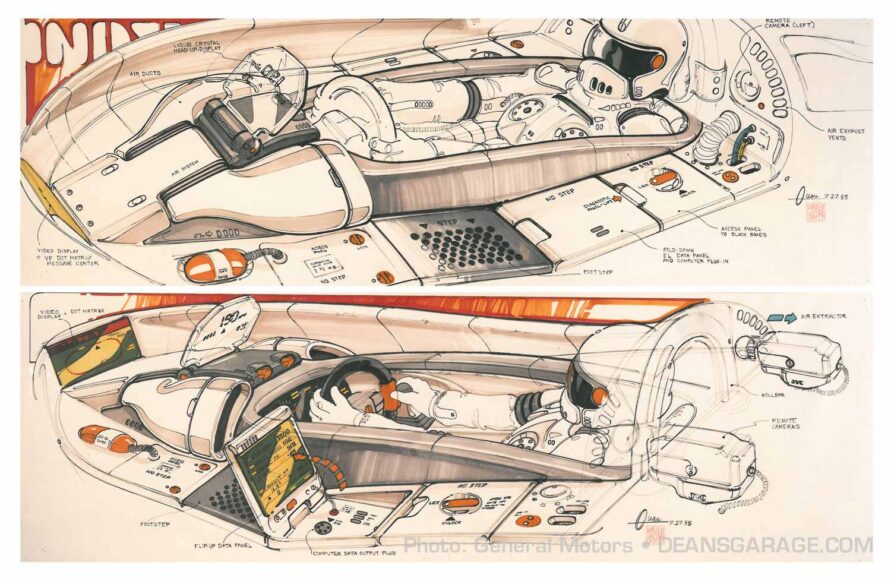

Quan: “The Aerotech was my favorite project because it was so blue-sky in terms of technology application with regards to the displays and panels. There were two variations of the Aerotech interior, one for the show car that would travel the auto show circuit and the other one for the actual running race car to be driven by A.J. Foyt. My design process involved a lot of inspiration from military aircraft, science fiction movies (Star Wars back then) and Japanese ‘Robotech’ toys.

“We worked with some very progressive engineers from the GM Delco Engineering group out of California to develop the working displays. The concept of the access panels came from the requirement of the test engineers that wanted easy access to the data recordings of each lap as a way to fine tune the car’s performance for the next lap run. So on each side of the driver were two flip up display panels that were used once the car was back in the race pit. Other access panels were for equipment or access to the on-board computers. Two integrated cameras were mounted just behind the driver. Two large vents brought in air from the front nose Naca-duct.” Sadly, the use of this highly sophisticated equipment in the very lightweight record cars was finally discarded.

Welburn: “Eighteen months is all that took from first sketch to running car.”

Actually, there were two 1987 running cars built, both to be driven by A.J. Foyt and fitted with special tires developed by GoodYear. March built the first car, which was originally intended to lap the Indianapolis Motor Speedway faster than any single-seater Indy car. It had a carbon-fiber built, short-tail body and a matching fully flaired underbody featuring adjustable venturi-tunnels. It also had a small and stylish rear wing of a NACA section, mirroring exactly the fiber-glass model’s appearance.

The second car, the long-tail, was built instead at Jim Feuling’s shop in California. It was dressed with a body-work and underbody supplied by March, if not for the streamline long-tail clip, built afterwards as a consequence of getting the approval to run the Aerotech both at the GM Proving Ground in Mesa and the Fort Stockton Test Facility. Both cars used the Robin Herd-designed March 85C aluminum honeycomb/carbon fiber monocoque chassis. A team of fifteen designers headed by Alan Mertens had produced every assembly and detail drawings of Herd’s design, with contributions from the up and coming Adrian Newey.

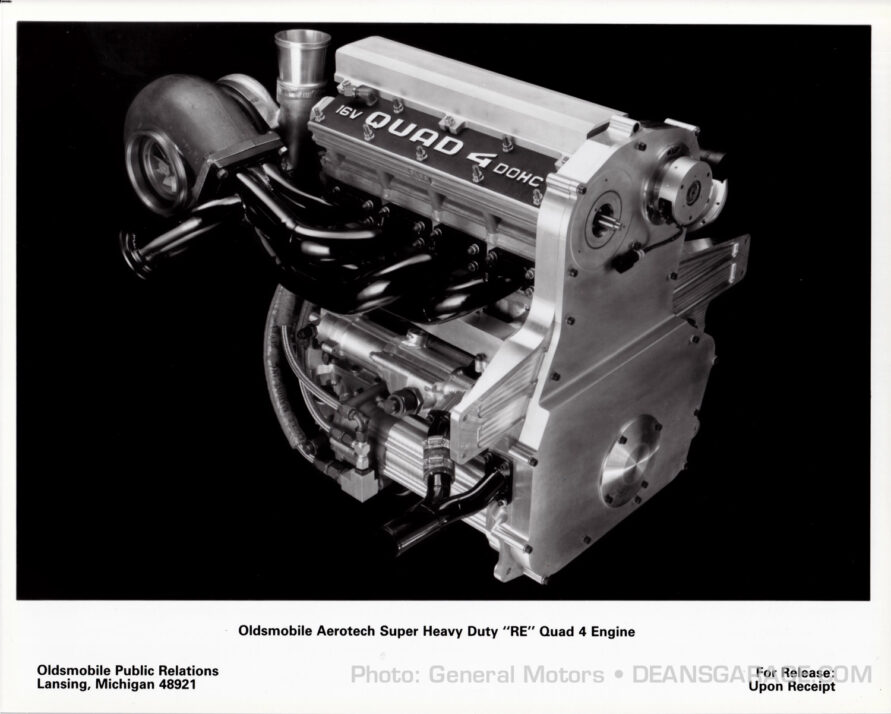

The 85C type was much lighter than 84C and twice as stiff. Its wheelbase of 111-inch was a very important factor in the design of the Aerotech. The two cars had Quad 4-derived engines, very different in between, though. These were coupled to a March transverse gearbox as used on Indy car racing on the ‘ST’ and to a Hewland unit on the ‘LT’. March’s ST car 2.0-liter Quad 4 ‘RE’ engine was built by Batten Engineering of Romulus, Michigan. It had a problematic and much delayed set-up phase on the dyno. RE was derived from a Quad 4 production unit and used methanol as fuel. A massive single Garrett turbo compressor and two injectors per cylinder were RE’s distinctive features. Its installation at the back of ST took place at Foyt’s workshop, 20 miles northwest of Houston. ST’s completion was overseen there by Hewell ‘Hughie’ Absalom, the legendary race mechanic, member of March at the time and the person who had actually built most of the car at March in Bicester. ST was the car used by Foyt for the ‘world’s closed-course speed record’ of 257.124 mph at the old Firestone in Fort Stockton 7.712 miles long oval test track set on August 27, 1987. This was an unofficial record, since there was no such officially recognized category.

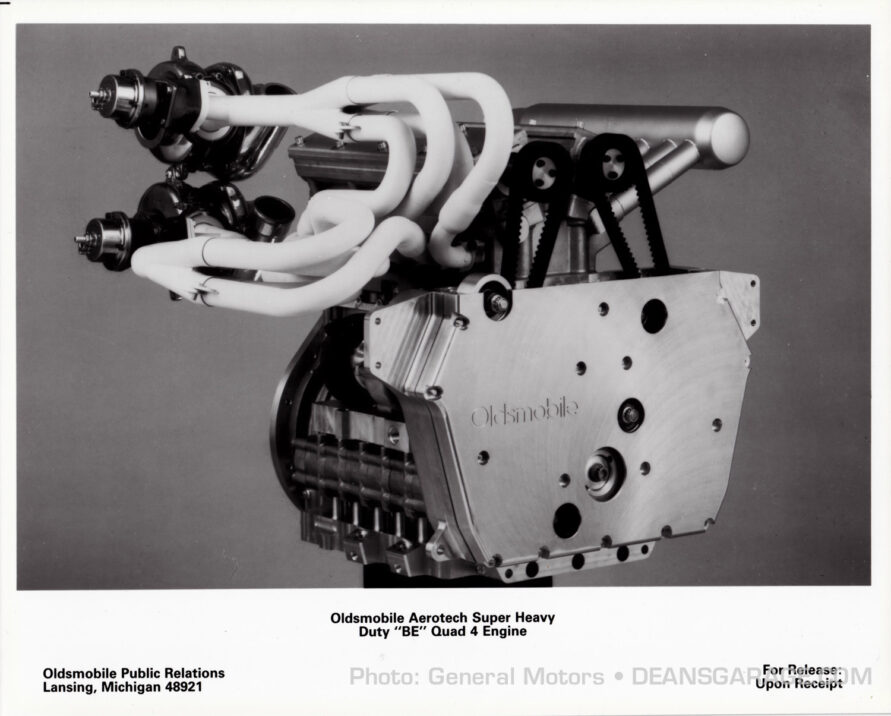

LT’s engine, called ‘BE’, was built by Feuling Engineering in Ventura and was a bi-turbo. Feuling started its design from a clean sheet of paper hiring Rocky Philipp and Keith Black as engineering consultants. Again a 2.0-liter, BE would make 1000 hp at slightly under 9500rpm at Fort Stockton’s for the official measured-mile speed record average of 267.399mph, achieved on that same August 27, 1987.

Foyt had topped 278.357mph through the mile on his counterclockwise lap at Stockton’s oval. Stepping down from the car he assured to be certain that in more favorable conditions 300mph were achievable; and the rumor about taking the car to the Bonneville Salt Flats was getting momentum. Both ST and LT cars were then taken to Indianapolis on October 22, 1987, in a try to break the current Rick Mears’ Speedway lap-record of 217.581mph, while of course keeping on with the implicit advanced engineering research of the whole project.

Unfortunately, both cars, ST and LT couldn’t perform any faster than 189mph because of mechanical problems. A car with a canopy and fenders at speed was really a rare sight at Indianapolis. “If they could find a way to put a couple of doors on them like a sports car, they would sell really well.” Foyt quipped, praising how comfortably and safely one runs at the track in such a car. He probably was not aware that Welburn had been working on subsequent sketches of an Aerotech two-seater street car variant, a flight of fancy which, in the end, could never win against the strong will of Chevrolet to finally pursue their own mid-engine Corvette street car, evidenced at the time by their own magnificent 1986–1988 Indy and 1990 Cerv III running concepts. Despite the problems and setbacks to be expected, Aerotech had fulfilled its promise and was now time to turn the page. But not to close the book.

1993. Visitors to the Detroit Motor Show can behold the ‘Endurance’ version of Aerotech, coming straight from, again, Fort Stockton. Both the ST and LT record-breaking cars had been re-dressed with an updated, perhaps less graceful, bodywork featuring a 917-esque different canopy, a taller and bigger air scoop and headlamps. A subsequent March 85C sourced from St. Louis was used for the construction of a third unit together with the revamp of the previous two at Bob Norwood’s shop in Texas. The three cars were assembled there to identical standards, featuring the streamliner type long-tail design. Aurora V8 L47 4-liter engines were fitted in the cars, whose purpose was again experimental and great speeds.

Welburn: “Those cars were a great way of profiling the capability of the Aurora V8. The engine was absolutely stock, and it broke 47 speed endurance records!” This time on Michelins, though. The only way to differentiate them was the color of the light beacon below the roof air scoop oval: red, white and blue, the colors on the national flag.

‘White’ was the previous ST, ‘Red’ the previous LT and ‘Blue’ the last built. Together with the fiberglass show car, ‘Red’ and ‘Blue’ belong to GM Heritage, as ‘White’ belongs to a collector who also owns all the replaced, original body components and engines.

Ed Welburn drove ‘Blue’ in 2010. It had been a long wait. On a sunny day of 2011, at Laguna Seca, he drove the Chaparral 2H, too. Shortly after he could also take the wheel of a 917 ‘Lang Heck’ (917-043) and drive it! The circle was closed, all childhood dreams had turned true.

Ed Welburn was named vice president of GM Design North America on October 1, 2003. He became the sixth styling/design boss in GM history, following the footsteps of the legendary names of Harley Earl, Bill Mitchell, Irv Rybicki, Chuck Jordan and Wayne Cherry. On March 1, 2005, Welburn was promoted to GM vice president, Global Design. In this newly created position, he was the first one in the role to lead all of the company’s global design centers. On July 1, 2016, Welburn retired after 44 years with the company, with Michael Simcoe taking over his role. The last project in which he still had a direct involvement is the contemporary C8 Corvette.

Thanks to Ed Welburn, Christo Datini, and Larry Kinsel of General Motors; William Quan, Matt Katz; David Reeves, Hughie Absalom, Tino Belli, and Andy Beuling of March.

Photos from the Archives of General Motors and Ed Welburn

Painting by Hector Luis Bergandi for Aerotech Press Kit.

Ed Welburn in Design Development, 1972.

Ed Welburn's Original Concept Renderings in Foyt's Coyote Orange.

Early Clay Model. Dave North, Kirk Jones, Ed Welburn, Steve Kozak, and Gary Clark.

Clay Model in Basement "Studio."

Clay Model in Basement "Studio" with Gilmore-Foyt March 84C Chassis.

Clay Model in Basement "Studio" with Gilmore-Foyt March 84C Chassis.

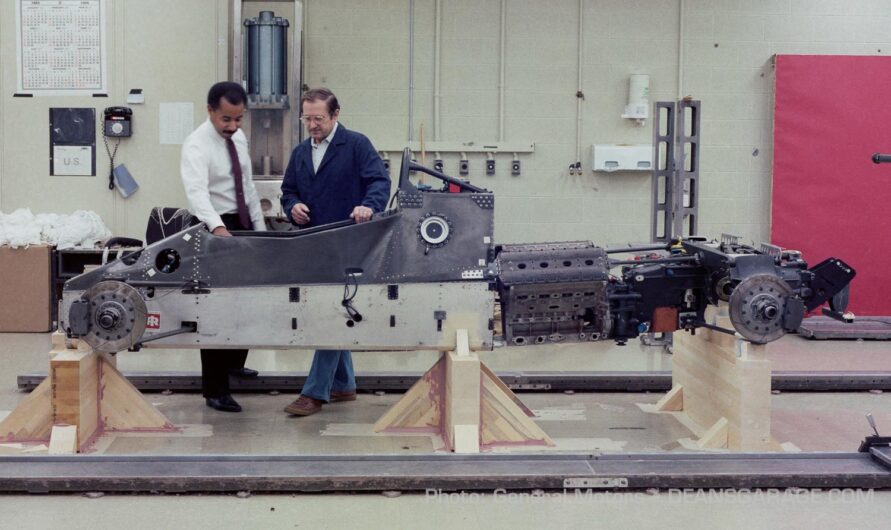

Gilmore-Foyt March 84C Chassis.

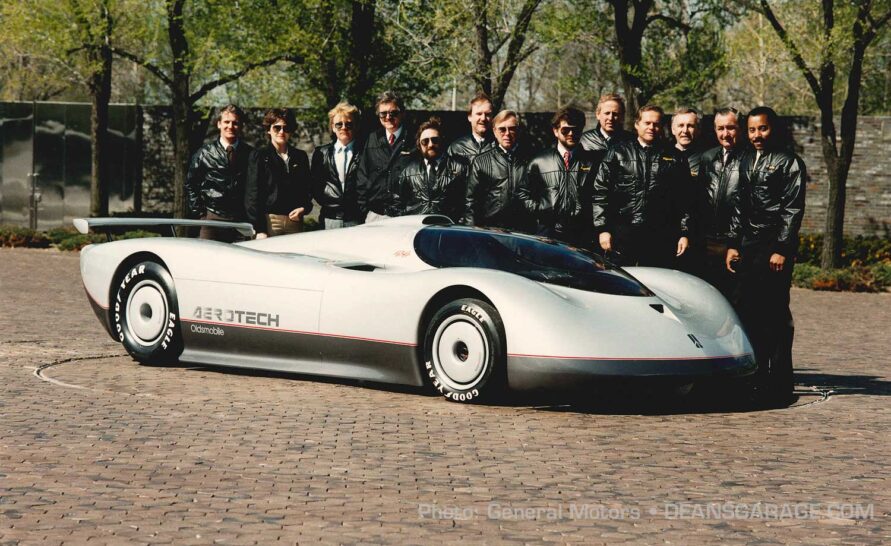

Oldsmobile 2 Studio with Fiberglass Model, 1986.

William Quan's Star Wars Interior Concept.

William Quan's High-Tech Interior Design.

Aerotech Clay Model.

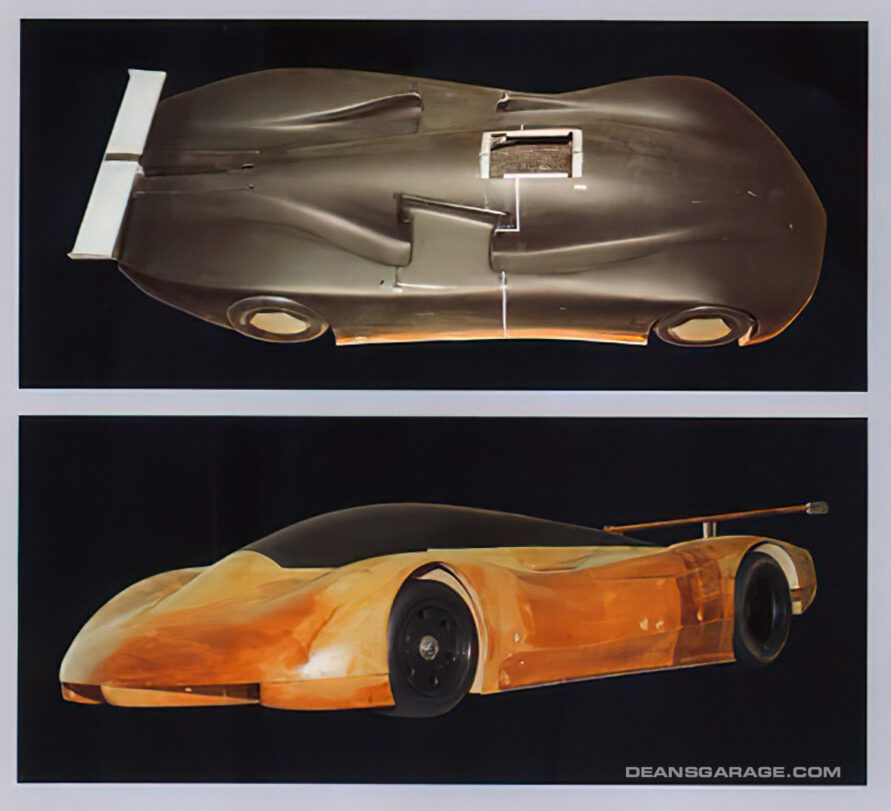

Long Tail Scale Wind Tunnel Model.

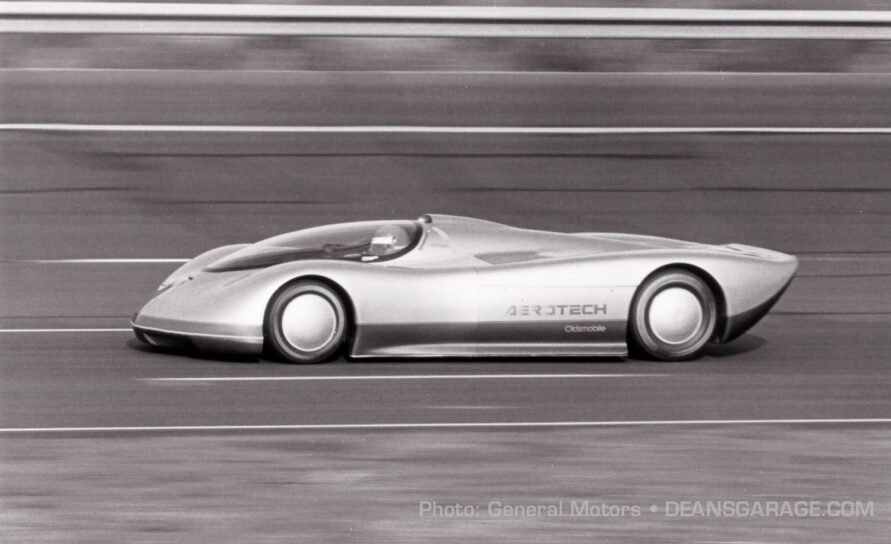

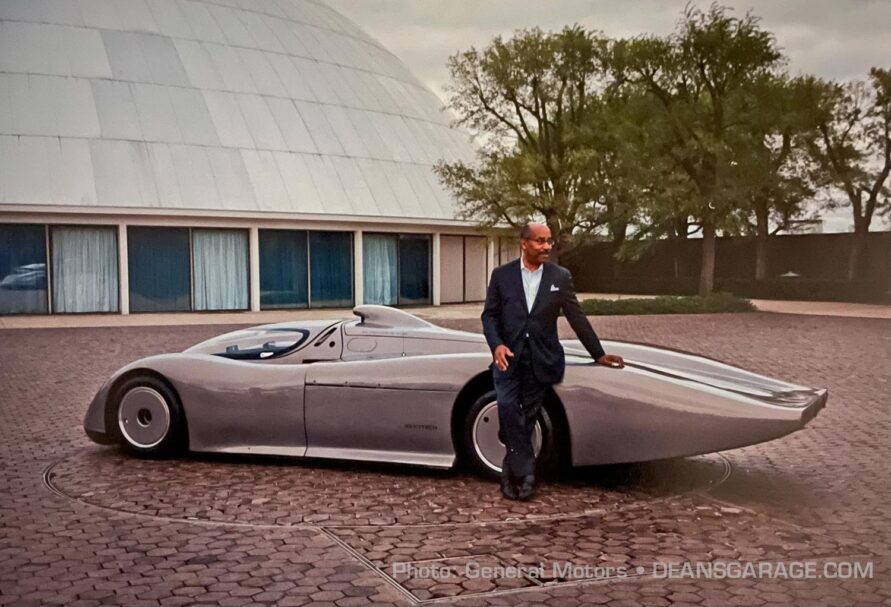

Aerotech Show Car.

March built Aerotech in GM Wind Tunnel.

RE Quad Four Engine.

BE Quad 4 Engine.

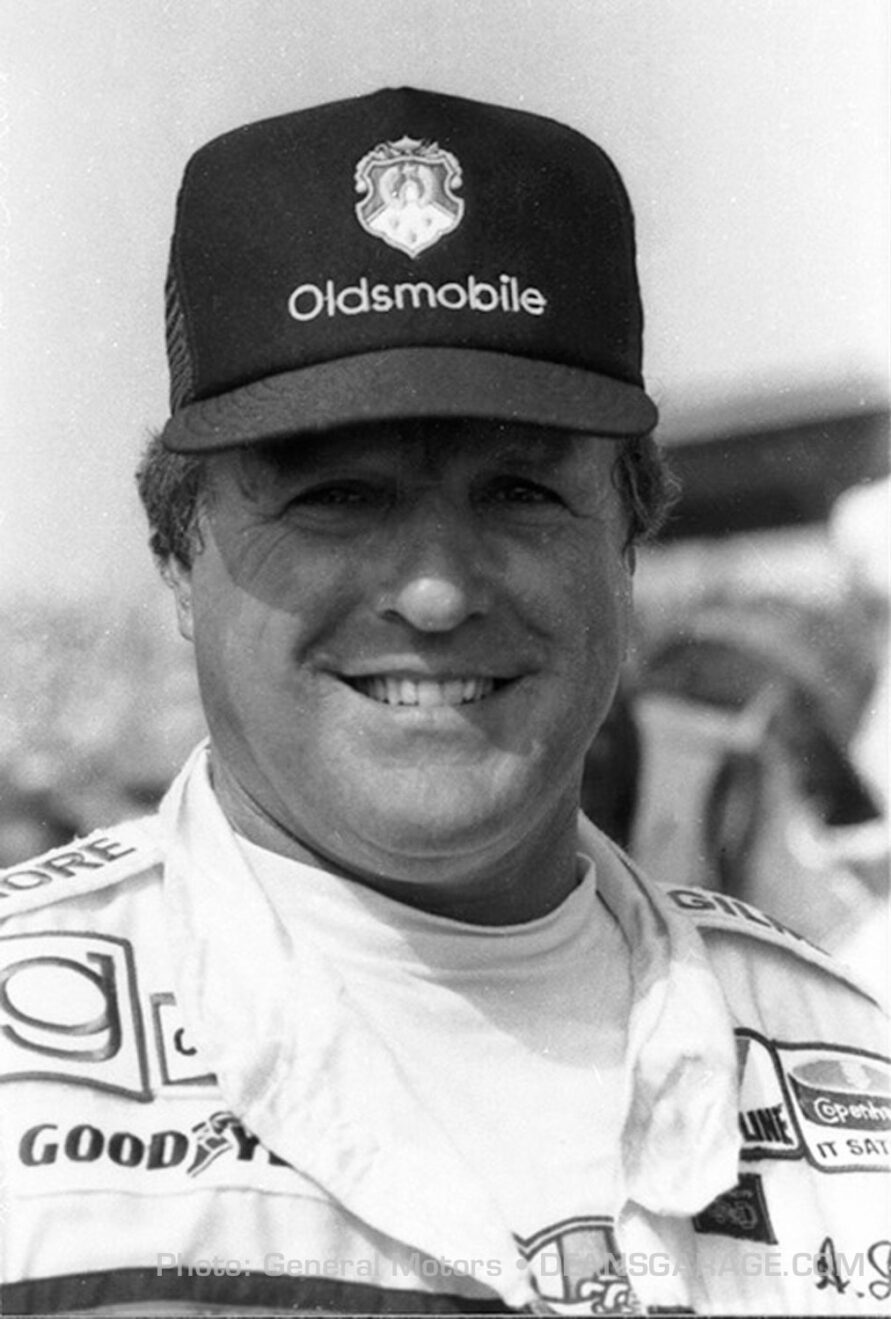

A.J. Foyt.

Wingless short tail during its shake-down laps with Foyt at GM's proving grounds.

Porsche 917LH (Long Tail) Rendering.

Aerotech IMSA Concept.

Aerotech Street Version Concept.

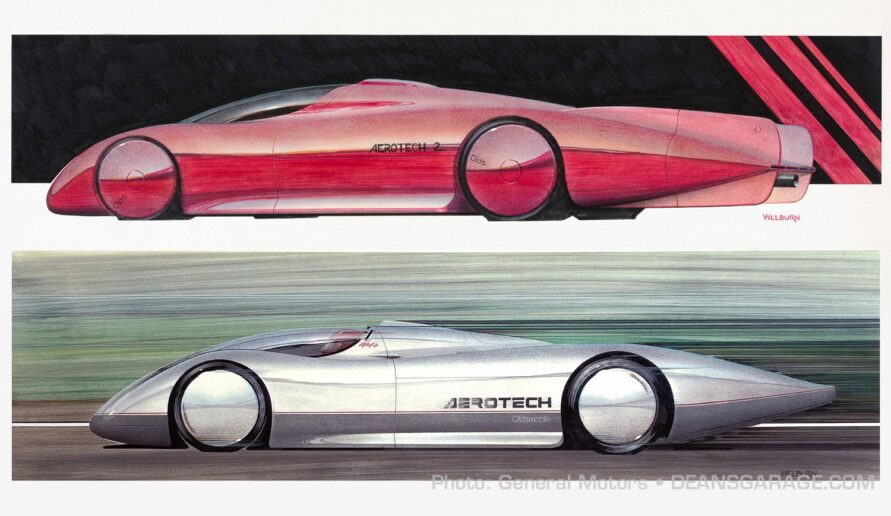

Long Tail Concept Renderings.

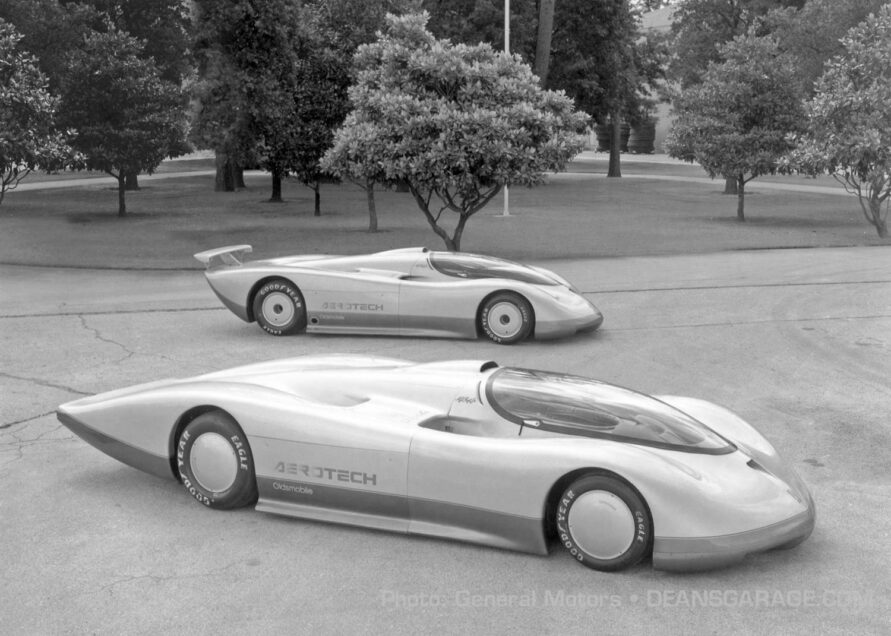

Aerotech Long and Short Tail versions.

Record breaking Aerotech-Aurora longtail.

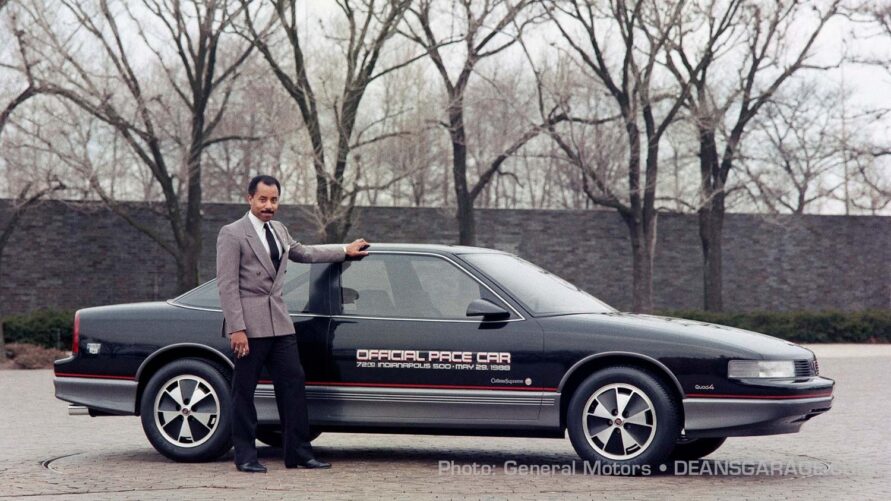

1988 Cutlass Indy Pace Car.

Photos Courtesy of David Reeves, March Engineering

GP Scale Wind Tunnel Models.

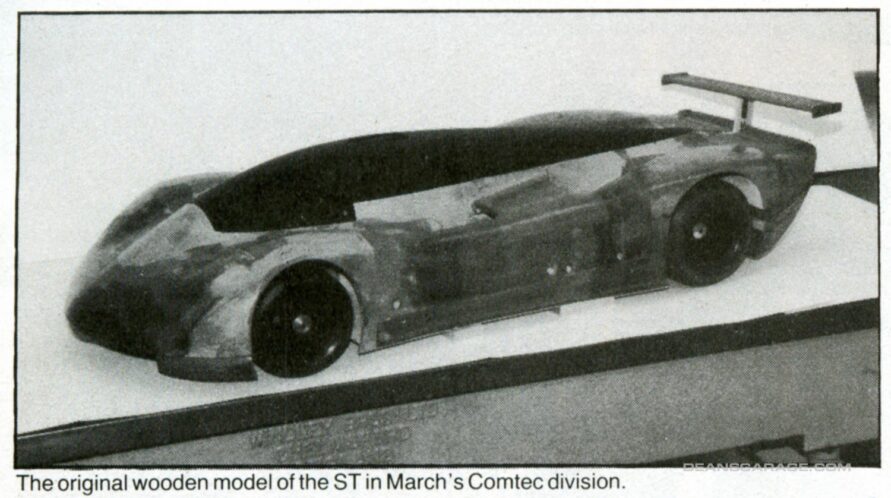

Comtec Wind Tunnel Scale Model, 1987.

David Reeves.

Short Tail at March's Assembly Shop.

Short Tail at March's Assembly Shop.

Composite Team at March's Brackley Facility.

Thank you for the story and interview with Mr. Ed Welburn. I have watched and read about him over the years. I especially recall his time in the Oldsmobile studios. I knew he was deeply involved with the Oldsmobile brand as well. I read and watched his growth and time at GM over the years. I wanted to be a car designer at work at GM at Oldsmobile/Pontiac/Holden. I never made it to GM, but I have always been so caught up the design of automobiles and the industry and the designers. I always enjoy when I read about Mr. Welburn or see him in an interview. I had no idea of the Oldsmobile Aerotech. I own and daily drive two Oldsmobiles: A 1992 Oldsmobile Toronado and 1996 Oldsmobile Ninety Eight. Thank you for this article.

Great story about the Oldsmobile Aerotech’s design and development.Congratulations fast Eddie, and thank you Gary for posting it.

Would there not have been the oil crisis and the down sizing then maybe the engine in the Oldsmobile Aerotech would have been the mysterious OW 43 DOHC V8.

The Quad 4 from Batten Engineering was the engine for a new time.

Mr. Wellburns 1989 Oldsmobile Cutlass looked so much better than all the Bimmers and Benzes of the times. There is a 1992 Cutlass convertible green here in greater Zürich Switzerland. Very nice condition.

Gary,

In the photo Clay Model in Basement “Studio” with Gilmore – Foyt March 84C Chassis from left to right are Dave North, Ed Welburn, Kirk Jones, Elizabeth Kohl, Gary Clark and Lee Paradise.

Gary,

In the Oldsmobile 2 Studio with Fiberglass Model,1986 from left to right are Gray Counts, Lee Paradise, Gary Clark, Kirk Jones, Robert Winkler, Charles Stewert, George Stoldt, Gary Mobley, Marvin Ashton, Dave North, Dave Birchmeier, Tom Krauzowicz and Ed Welburn.