John E. Herlitz, Chrysler Designer

Text: David Rodríguez Sánchez

Images: Todd and Kirk Herlitz, Stellantis, General Motors

“I started sending sketches of cars to Chrysler when I was thirteen. Sketching was something I was doing since I was four, when I used to name all the cars on the road from the back seat of my dad’s Oldsmobile. I was so amazed when I got a response from Chrysler, providing me with all the guidance on where to go to school, a lot of encouragement and even some studio illustrations. I just could not believe it.” This is how John’s great career in car design began. Though never taking credit for any of the many successful designs he worked on from Chrysler, Plymouth or Dodge brands, John Herlitz’s design work on such icons as the 1970 Plymouth Barracuda and the 1971 Road Runner stands out.

John Herlitz’s father Steven emigrated to the United States from Sweden when just nineteen years old. An entrepreneur, he found success with his eponymous medical advertising firm located in midtown Manhattan. While being treated for pneumonia, he met Karen, a nurse. John was born in New York City on December 30, 1942. When Steven and Karen separated, John continued to live with his mother in Pine Plains, New York, until college. He then moved to Manhattan and stayed with his father.

In 1960 John started attending Pratt Institute of Design in Brooklyn, New York, majoring in Industrial Design, where he “learned that sheet metal is a sculptural element and you should treat it that way.” Pratt was the place that had been suggested to him by Chrysler’s styling staff with whom he had kept frequent correspondence. At the end of his studies at Pratt, which had also included a summer internship at GM’s Design Staff in 1963, John got his first job at Chrysler Corporation styling studios in July 1964. It seemed like coming home since in 1952 John’s father had purchased a Chrysler Saratoga.

His first assignment would be to work on the design of the Plymouth Barracuda. He told Collectible Automobile: “My first car project was the 1967 Barracuda program. And there were three phases to that program. There was one that was the formula of the original Barracuda, which was just a fastback Valiant. And then there was phase two, which was to do a total reskin of the Valiant holding the windshield. And then phase three (or Formula SX Barracuda) was to do an all-new car from the ground up, but remained just a fiberglass shell. That was the one that I got to work on and that was the one that was the lead proposal by the time I went into the Air National Guard. Six months later the die had been cast on the program. However, there was no way that they could finance an all-new Barracuda at the time, so they had to scrap that. But they used the theme from the phase-three car and my colleague Dave Cummins adapted it marvelously to the phase-two, re-skin program.”

John was then assigned for a short period of time to work on large C-body projects during 1965. Next came the 1970 E-body Barracuda project, with prospected 1969 and 1970 facelifts to the 1968 Road Runner. “We knew that to be really serious in the pony car business we had to get to the big powertrains and so, therefore, we kind of co-engineered the ’71s; the Road Runner, and GTX, and Satellites, and Chargers, so that the cowl and plenum were shared between the car lines. That got us into the big engine boxes and the big engines.”

Dodge and Plymouth studios were always in a strong competition because their respective Challenger and Barracuda bodies were due to share some elements, despite a slight but crucial difference in wheelbase for brand differentiation: “This was an exciting program because you got to work very closely with the powertrain engineering group. It also gave us the opportunity to work with the aerodynamics guys, and the engine-breather guys on the shaker hood; while also working very closely with the interior guys trying to get a harmonious interior/exterior theme quality.”

Herlitz had been promoted to studio manager in late 1968, where he was responsible for the intermediate cars. For the 1971 Barracuda, only the rear lights and windshield were to be common with Charger. The project had some interference from Elwood Engel, the corporation’s ex-Ford Design VP at the time, proposing a ‘too personal’ take on the theme: “I observed that if you’re a design manager, you ought to be just that and not be constantly competing with the designers on the board whose job it is to create.”

Engel, the replacement of none other than Virgil Exner at Chrysler, with the 1963 glorious Turbine car to his credit, retired in 1973. Richard G. Macadam succeeded him: “Dick was the best mentor that I ever had in design, coming on board at the worst possible time. We had the energy crisis and the financial cutbacks. We had to put together a somewhat competitive product line with nearly no budget. We could make it into the late seventies, when Hal Sperlich came over. Hal and Dick got along quite well, but Lee laccoca could not stand Dick. Shortly thereafter, former Ford designer Don DeLaRossa came in as a consultant, and pretty soon Dick had to go. It was 1980.”

Herlitz was the studio manager behind the F-body and the Volare/Aspen programs, leading later to the small K-Car Program, which resulted in the ‘World Car’ Omni/Horizon. For the time of the K-Car program, as per his boss Macadam’s wish, Herlitz was having his own personal experience with interiors, trim and color, so that his preparation would be complete if he was destined to go on up the ladder within the company.

Interiors and color were headed by Colin Neale, who also ran the increasingly important task of international operations. DeLaRossa’s deputy was Roy Axe, of Rootes-Austin-Rover fame from the UK. As of October 1981, with Axe back to Britain, DeLaRossa promoted John Herlitz and Tom Gale as design directors, both ever trying to stay loyal to the design principles which Iaccoca firmly believed had been the key to his successes at Ford and bring actually something fresh and new.

Commenting on the K-car and derivatives, the ground-breaking minivan, the Imperial, Le Baron and the coupes, John said, “We were all really turned on by those cars, but we were stuck with a four-cylinder power train. There’s just some things that design can’t overcome and rudimentary mechanicals is one of them. Still, we launched into the four-cylinder turbos, people bought a lot of those cars and we made a lot of money on them.”

Because of a progressive, ever modest product development investment, Chrysler’s cars in the 1980s and still beyond would finally get what originally they would have needed only at the end of their commercial life-cycle, which constituted a bitter paradox. For its innovative design language, Herlitz remained keen on a 1979 K-car based Steve Bollinger-designed study for a joint Chrysler-De Tomaso sports car, an unreleased ‘Pantera II’ that was recycled as the 1982 Stealth concept car. 1982 was also the year in which Herlitz was promoted to Interiors and Color, Fabric and Mastering design direction.

By 1985 he was promoted to the direction of Exterior Passenger Car Design. The stylists were now commonly referred to as designers. Their profession was transforming fast to the standards of the modern, digitally controlled world, where computer-aided design (CAD), modelling or manufacturing (CAM) and styling (CAS) were becoming omnipresent, a fundamental tool for virtual simulation of every possible parameter, as well as the key-code in the relationships between the design and engineering teams. The artistic skills of the design staff were more and more assisted by dedicated software. Still, creativity and innovation remained beyond the powers of the computer.

Chrysler had a staff of about 60 designers by 1987, plus Pacifica, the advanced design operation in Carlsbad, California. Design process began as many as 280 weeks before the scheduled planned production, the interiors one of the priorities, as the tooling for them took much longer to manufacture than the one for the outside panels. Styling-wise, vinyl roofs and boxy designs were now an anathema. The round and solid 1987 LeBaron, either in its coupe or convertible version, ranked on top of Herlitz’s designs of the late 1980s. He inadvertently poured onto them his passion towards Pininfarina’s Ferrari 308 and BMW’s 6-series by his friend Paul Bracq.

With the 1987 Chrysler-Lamborghini Portofino, the cab-forward era of Chrysler was foretold. Golden days in design at Chrysler lay ahead; they would owe a lot to the positive and dynamic influence of the new Chrysler brand president Bob Lutz from Chrysler’s magnificent styling past, he wanted to revive Iaccoca’s old-fashioned tastes.

The flow of the most-exciting, unrestrained concept cars from the Chrysler, Plymouth, Dodge, Jeep, and Eagle brands followed the Portofino year after year, often stealing the Detroit shows from European, Japanese and domestic competitors. That brought the names of Bob Lutz, Tom Gale, John Herlitz, and Neil Walling (head of the International Design Studios of Chrysler) to the hottest interviews at the shows and newspapers and magazines world-wide afterwards.

The 1979 Government Bailout of Chrysler echoed ominously through the late 1980s recession, but again renaissance was around the corner. In 1993, Herlitz was promoted again to be an active part in it, getting the Car Exterior Design Director position. All operations had been transferred from the Highland Park historical site to the new, world-class CTC (Chrysler Technology Center) in Auburn Hills, Michigan.

The new LH platform incorporated ‘synchronous engineering’ methodology that saved resources to the ever struggling corporation. Chrysler was ready to step away from the most recent critical crisis. In 1994, Herlitz was named Vice President for Product Design, turning into Senior Vice President of the newly established DaimlerChrysler Corporation by November 1998. John moved beyond the many successful compacts, midsize and luxury sedans, trucks, minivans and SUVs. He understood that the public was becoming uninspired by the rather mundane passenger cars that industry was putting on the market.

Besides his tireless work behind the secret walls of the ever growing styling departments, Herlitz had become also an easy and sought-after communicator, the reference point for the press and media when it came to first-hand learning about the new concepts and products, of constantly growing interest to the public, and the corporation’s vast and rich design legacy, its present and future. Self-described as one of the ‘Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse’ running the design studios of Chrysler along with Tom Gale, Trevor Creed, and Neil Walling, Herlitz was finally appointed Senior Vice President of Design, Special Assignment for DaimlerChrysler on July 1, 2000. In this role, he was meant to oversee the transition phase in the design studios prior to his planned retirement in early 2001.

Chrysler design studios had set the bar for the American post-modern automotive design for his last fifteen years at the company. Upon his retirement day, he was thinking of opening a design consultancy. Fate, though, had different plans. John’s wife Joan became ill and died as a result of complications. John and Joany (as those who knew them well called her) were a true love story and they were together almost constantly when he wasn’t at work, the more then when he retired. Shortly after her death, John fell in his bathroom at his vacation home in Florida. He died on March 24, 2008 at the of age 65.

Chrysler designer and design manager Ernie Barry had this to say about John: “John Herlitz was a highly respected leader as Vice President of Design and well liked by his staff. He was personally responsible for the 1971 Plymouth Satellite, a beautiful and highly underrated design of that era. More importantly, John was a good friend.”

Dennis Myles, Chrysler design and design manager: “John and I attended the same design school, Pratt Institute in New York at different times, so we shared a design education background. John was already in senior management by the time I arrived at Chrysler and I did work for him during those early years with the company. John was a good person to work for and with because he empowered his people to take responsibility for their work and guide the product development thus being accountable for the results. When Tom Gale was elevated to full Vice President, he appointed John to run the design office. Tom chose John because he was an outstanding people person as well as a good designer. During the many executive reviews, usually scheduled weekly, he would offer his thoughts and together the next phase of development was agreed upon but the designer was in charge. John was a very fine person and I’m glad I knew and worked for and with him.”

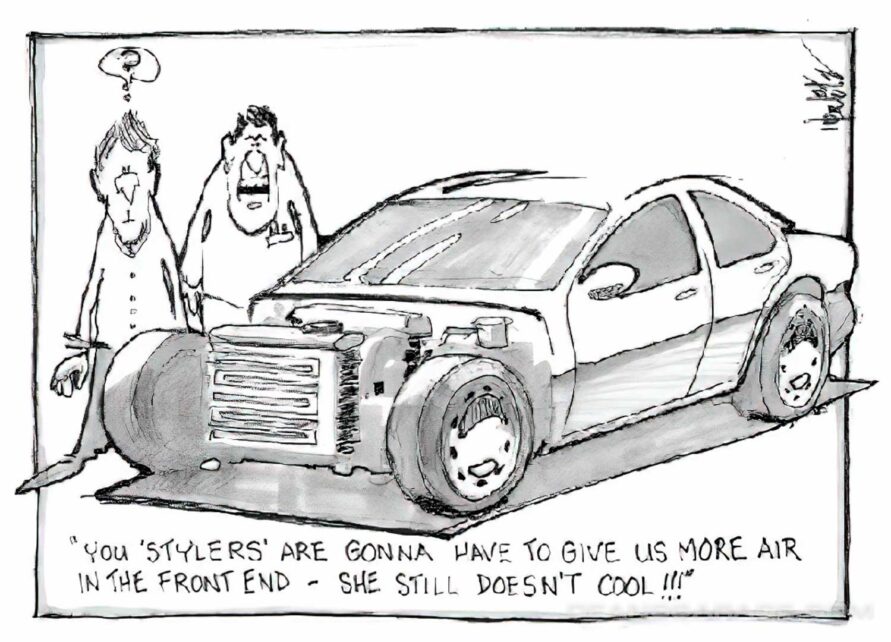

Bob Lutz: “John was a brilliant designer and a multi-gifted person. He had an excellent sense of humor. He was a superb cartoonist, with regular contributions appearing in Chrysler’s employee newspaper. His cartoons were of a high level, artistically, and very funny. John could have easily made a good living as a professional cartoonist. I was very much saddened when he passed away at such an early age.”

Todd Herlitz: “Dad spent a lot of time attending and judging car shows like Pebble Beach and Eyes on Design. He had a big collection of automotive history books, mostly focused on Muscle Cars, Chrysler History, and European automotive design. Dad was a real fan of Giugiaro and actually owned a 1986 Turbo Esprit for a number of years. He also was fond of Paul Bracq. Dad loved nature, probably because where he grew up was a small house surrounded by woods. Growing up, we did a lot of fishing together and long hikes in the woods behind our house. He was on the board of directors at Interlochen, a music and art school located in northern Michigan. He loved attending the classical performances there and also at Meadowbrook, an amphitheater near Auburn Hills. Always the problem-solver, he actually designed and built his own table that had an adjustable foot so it would stay level while sitting on the sloping lawn of the amphitheater. He always got a kick out of testing out the sound systems in new Chrysler products by cranking up some really powerful classical pieces, sometimes asking us to join him in the driveway to hear for ourselves. He usually set aside Sunday mornings to catch up on office work and would usually do some informal thumbnail sketching on design programs to work through some ideas.”

Thanks to Danielle Szostak-Viers of Stellantis, Christo Datini and Larry Kinsel of GM, Dennis Myles, Ernie Barry, Bob Lutz, Todd and Kirk Herlitz for their contributions to this article.

Edited by Gary Smith

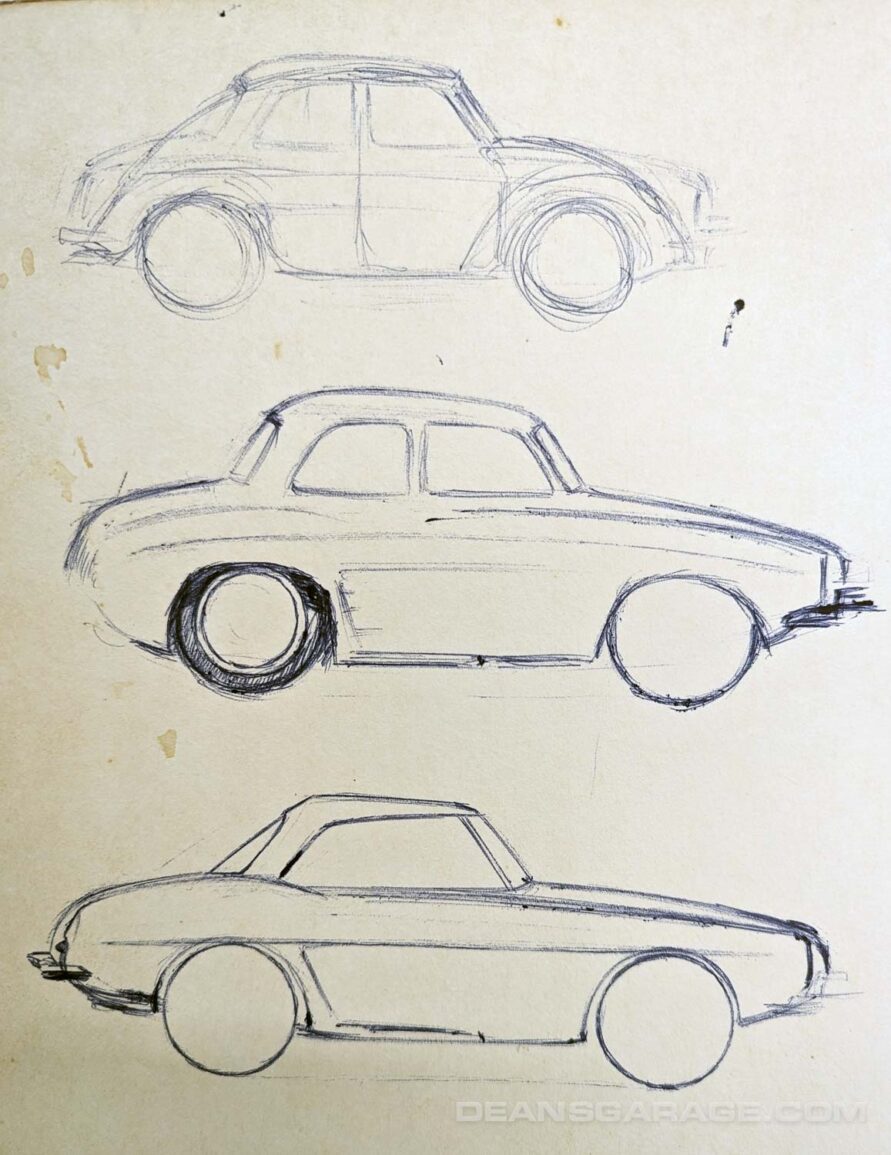

School sketches,1950s

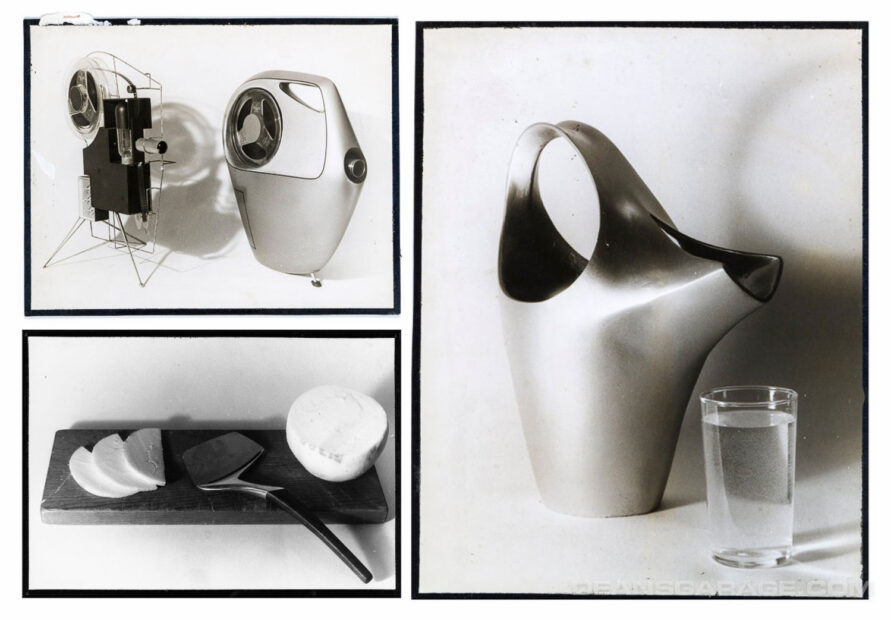

Industrial designs while at Pratt, 1962

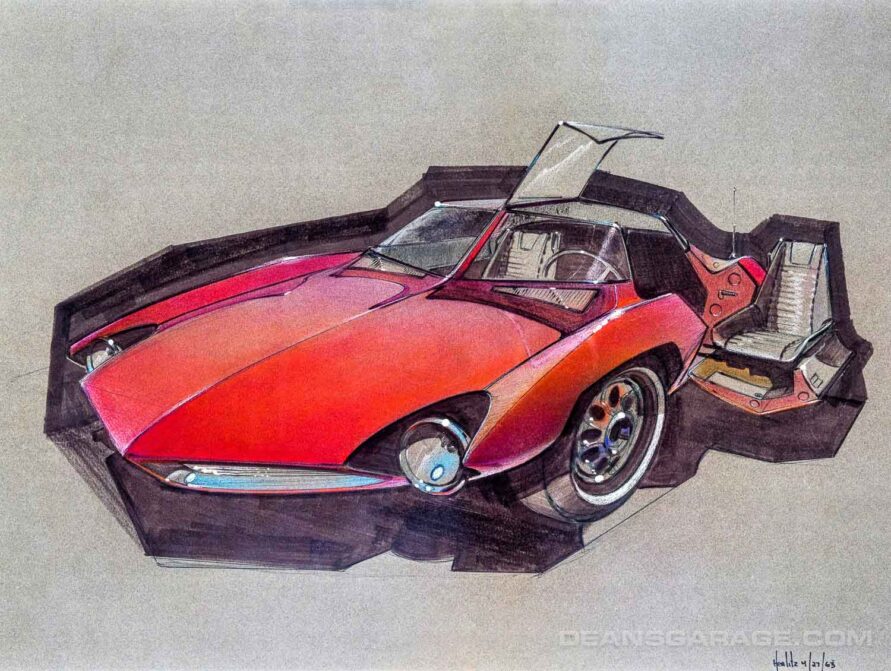

Sketch while at Pratt, 1963

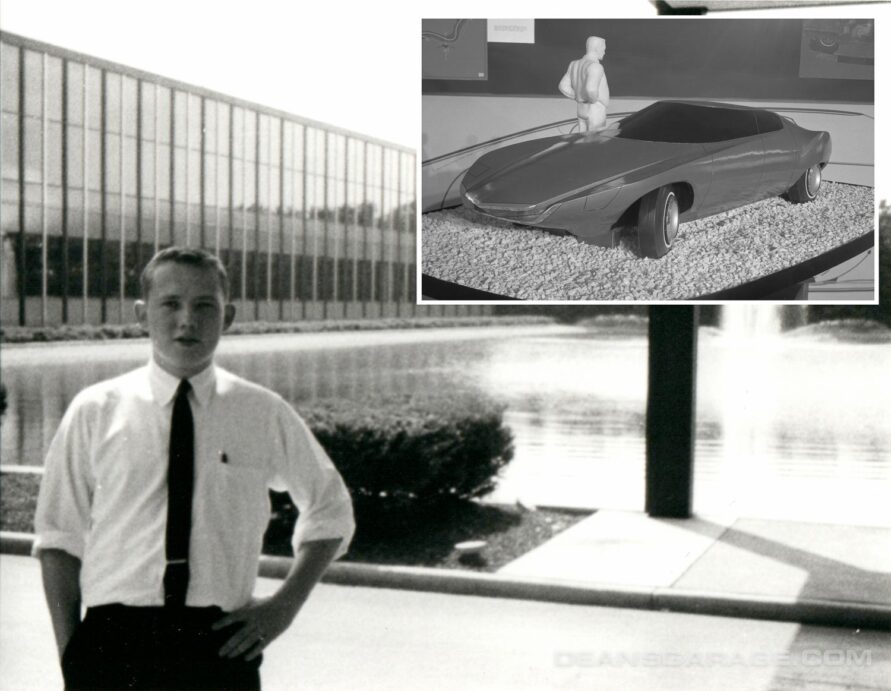

1963 Summer internship, GM Design Staff

1965 Plymouth Fury concept

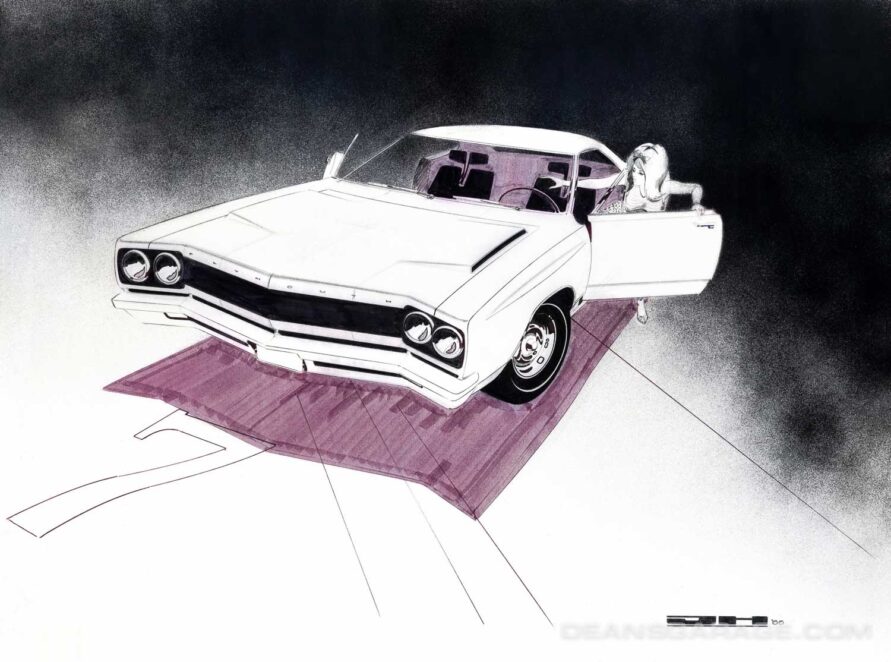

1967–1969 Plymouth Barracuda concept, 1966

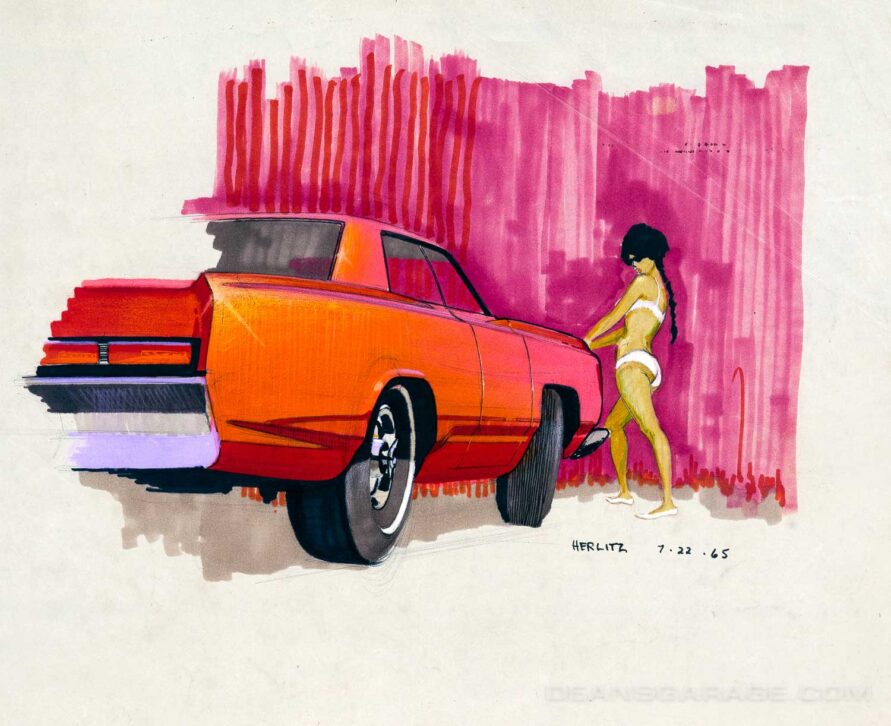

1968–1970 B-body GTX-Road Runner design, 1966

1968–1970 B-body GTX-Road Runner design, 1966

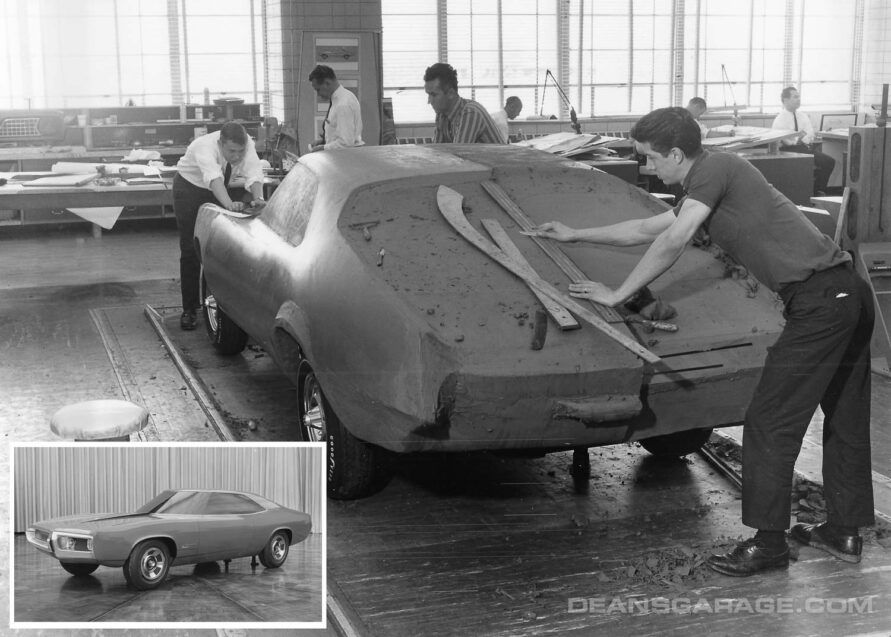

C-series Barracuda clay model, 1966

John Herlitz working on the 1967 Barracuda SX show-car clay model, 1966

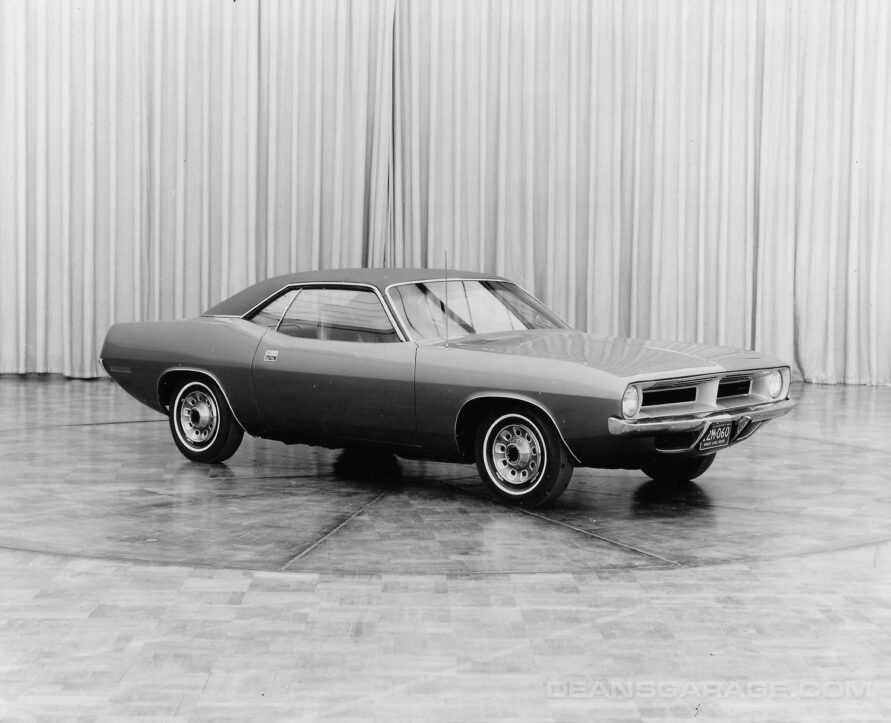

E-Body Barracuda fiberglass model, 1967

1970 E-body Barracuda fiberglass model, 1968

1971 Plymouth GTX-Roadrunner clay model, 1969

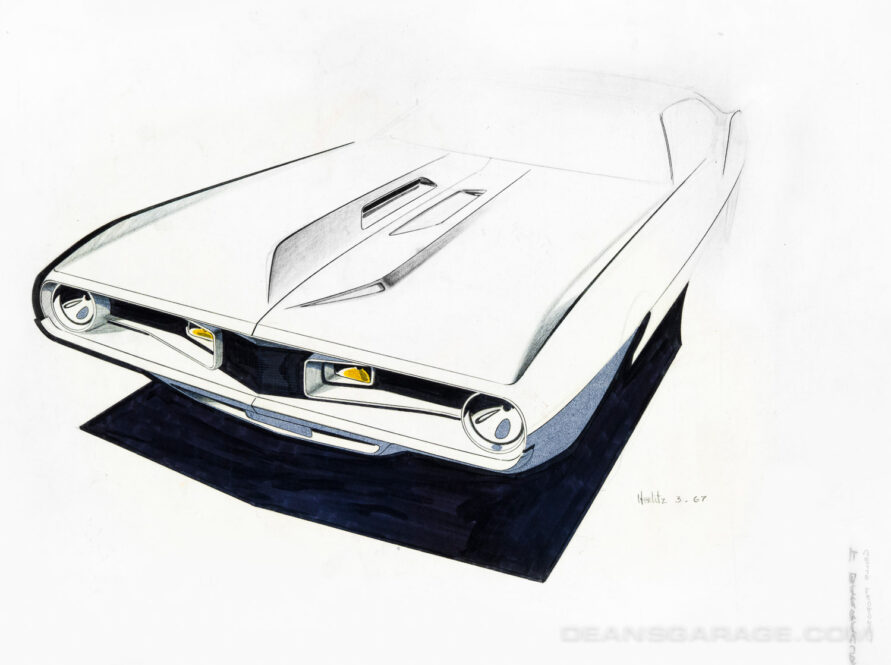

1970 E-Body Plymouth Barracuda design

1970 E-Body Plymouth Barracuda hood detail design

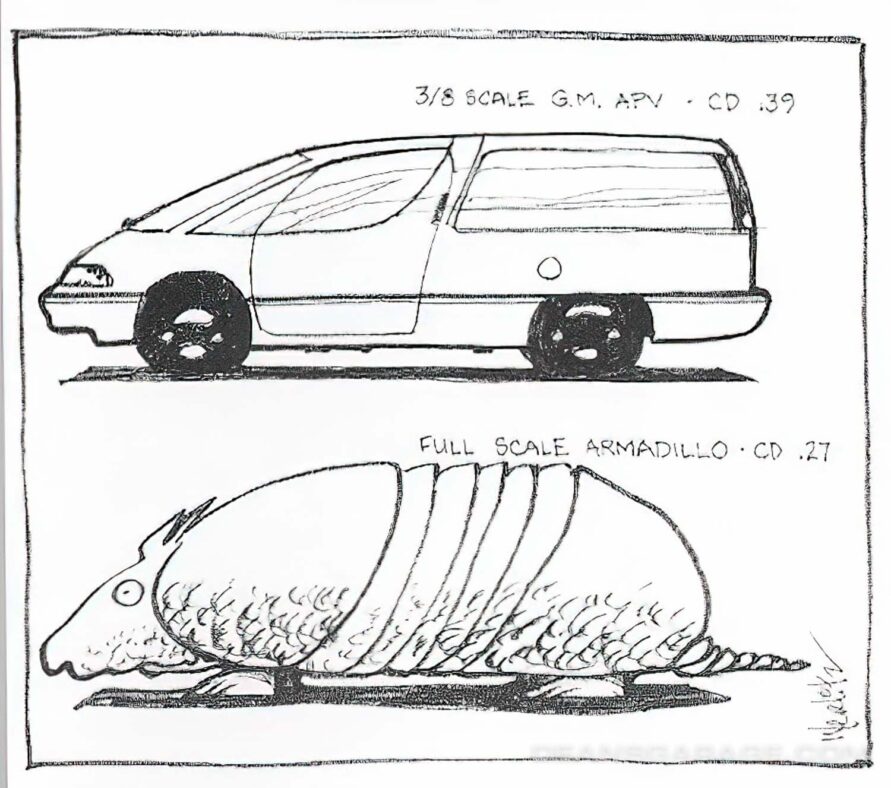

Cartoon joking about the shape and CD figure of Pontiac's Trans Sport

Cartoon on the engineering demands to Styling, 1990

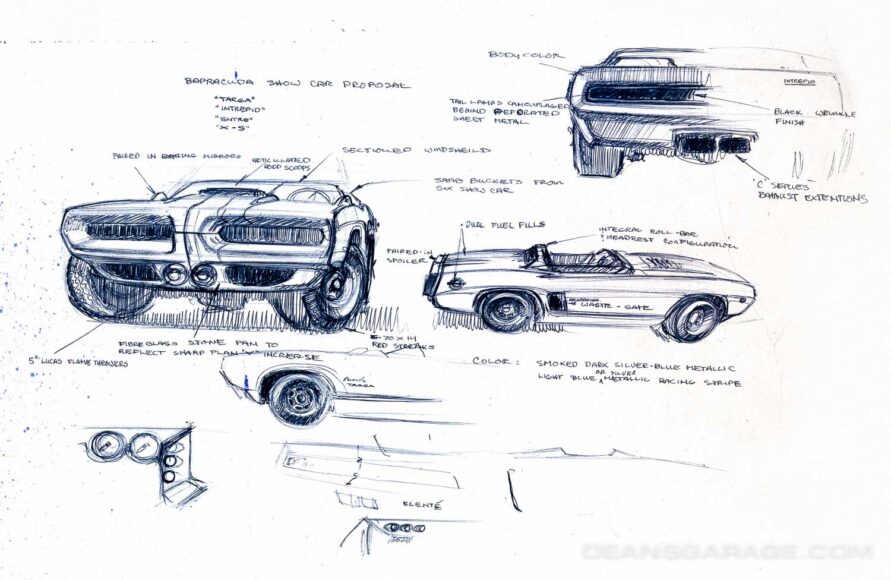

Barracuda show car proposal doodles

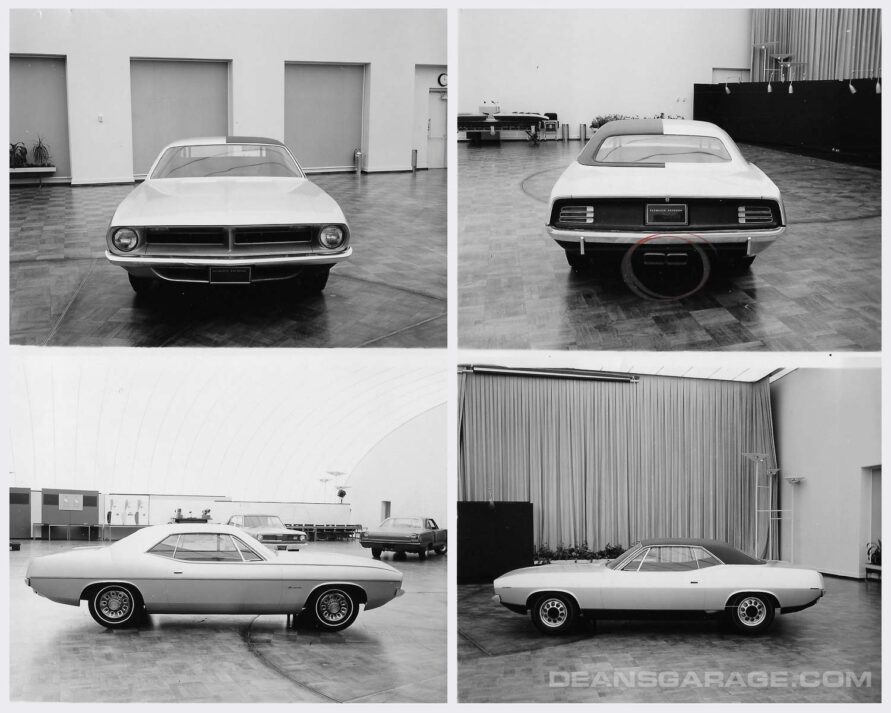

1970 E-body Barracuda fiberglass models

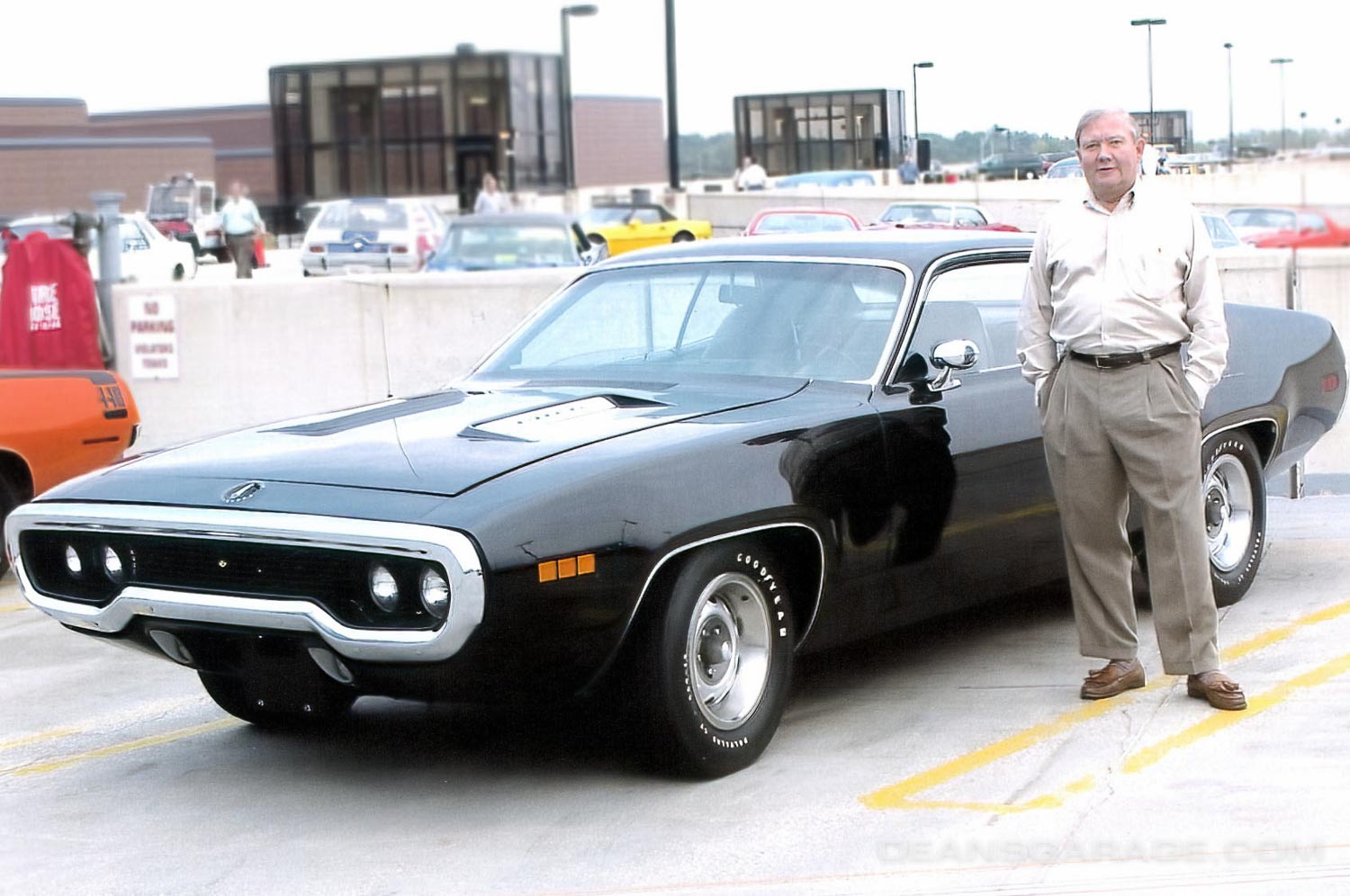

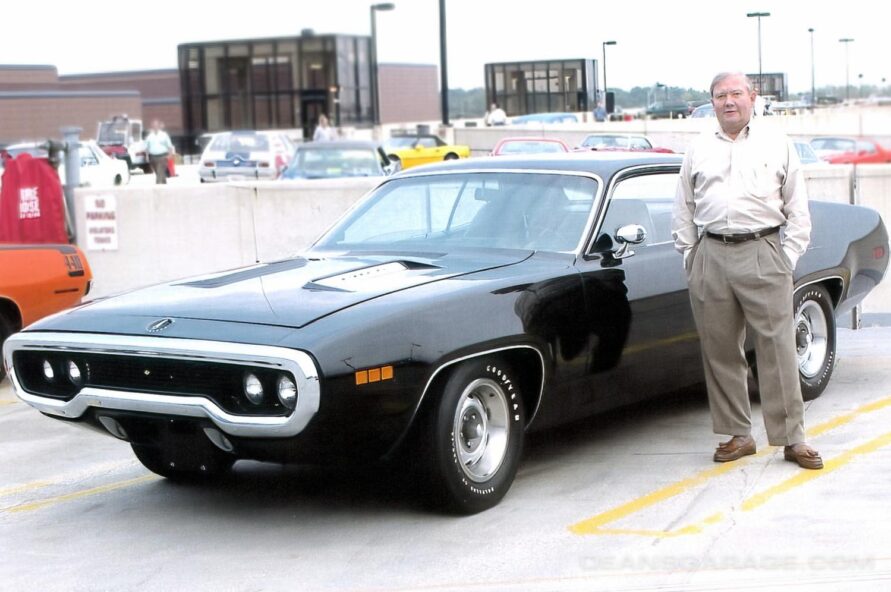

John Herlitz's 1971 Roadrunner, 1990s

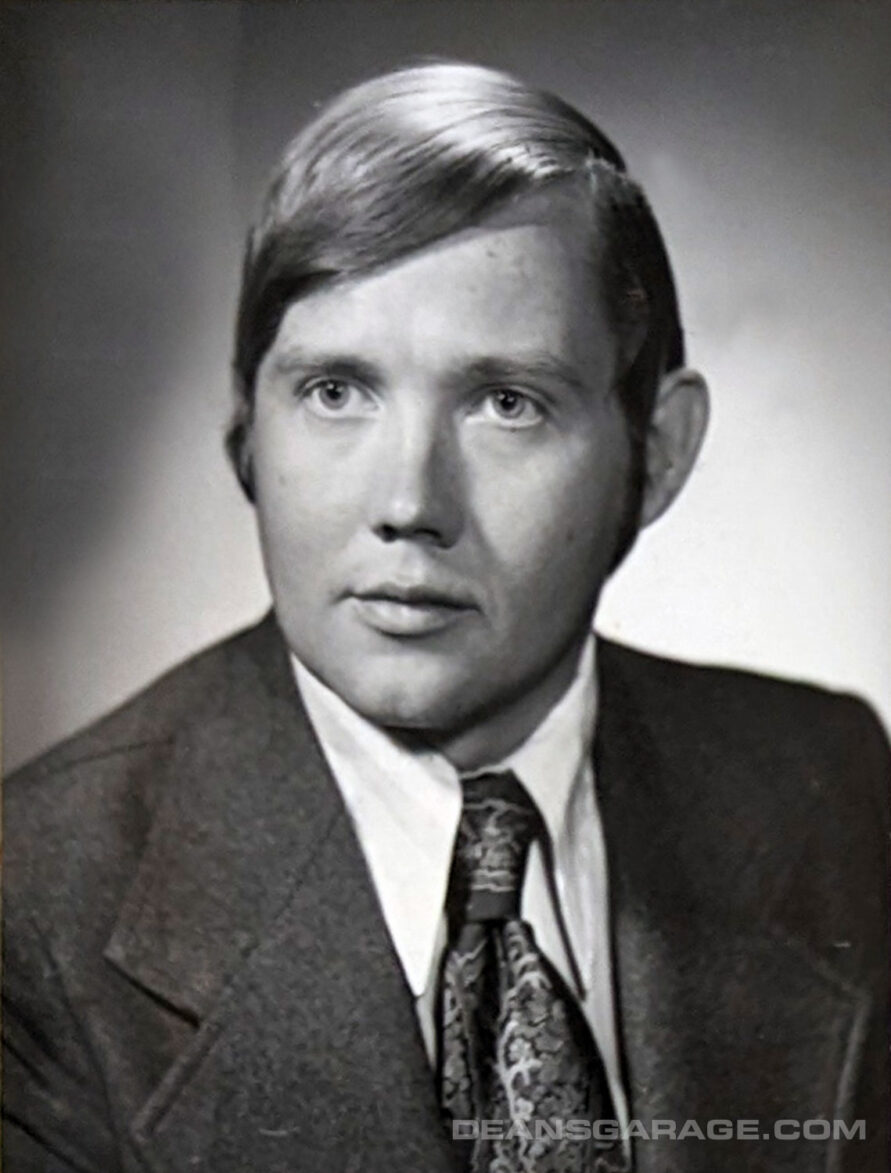

John Herlitz, 1968

John Herlitz, 2000

John Herlitz's caricature of the Road Runner trimphant over (Dodge's) Super Bee

Thank you for this piece on John Herlitz. I just finished reading the current December 2025 issue of Collectible Automobile, whose cover story is about the 1967-69 Plymouth Barracuda. It brought back memories for me of my preteen years, seeing the first 1965/66 version with the oversized rear window that was crushed by the Mustang’s introduction, but then the 1967-69 version, As it turned out, one of those (a coupe) was bought new by a friend of my older brother and so I regularly got to see it up close. It was nice enough in retrospect, but the Valiant origins still were quite apparent and didn’t seem to compete very well with the Ford and GM competition. The 1970 design was a different story, with great exterior design. It always fascinated me how Chrysler’s designs under Engel in the mid to late ’60s always looked like they were designed with a T-square, boxy to the extreme, and I often wondered how those working in Chrysler design must have felt about what they were directed to draw and what was getting approved for production compared to the Ford and especially GM competition. It was as if the French curve was never taken out of the drawer!

A really excellent portrayal of the evolution of a designer from his first steps to design and image leadership. There are a lot of very sharp automobiles along the way!

Thanks for another exciting, fine biography. I especially love the General Motors Pontiac Armadillo APV. Without doubt one of the grossest monstrosities to ever crawl out from under Detroit. Reminds me of that neon-tinged mistake of 1967-1969, Ford’s New All Electric Thunderbird Vacuum Cleaner.

Dave Jenkins, CEO of Edsel Division’s advertising arm, had pet names for some of Detroit’s most aggressively bad designs: Anyone care to hazard a guess which cars these identify?

“lollipop on the trunk”

“big chrome shovels on the sides”

“highway flares on top of the rear quarters”

“braces in its teeth”