John Houlihan

John Houlihan

John Houlihan is a familiar name to readers of Dean’s Garage having been featured in three previous posts:

Who designed the ’71 Boattail Rivera?

How the Vega Kammback Came to Be

John also had participated in several League design projects, including last year’s Pierce-Arrow project.

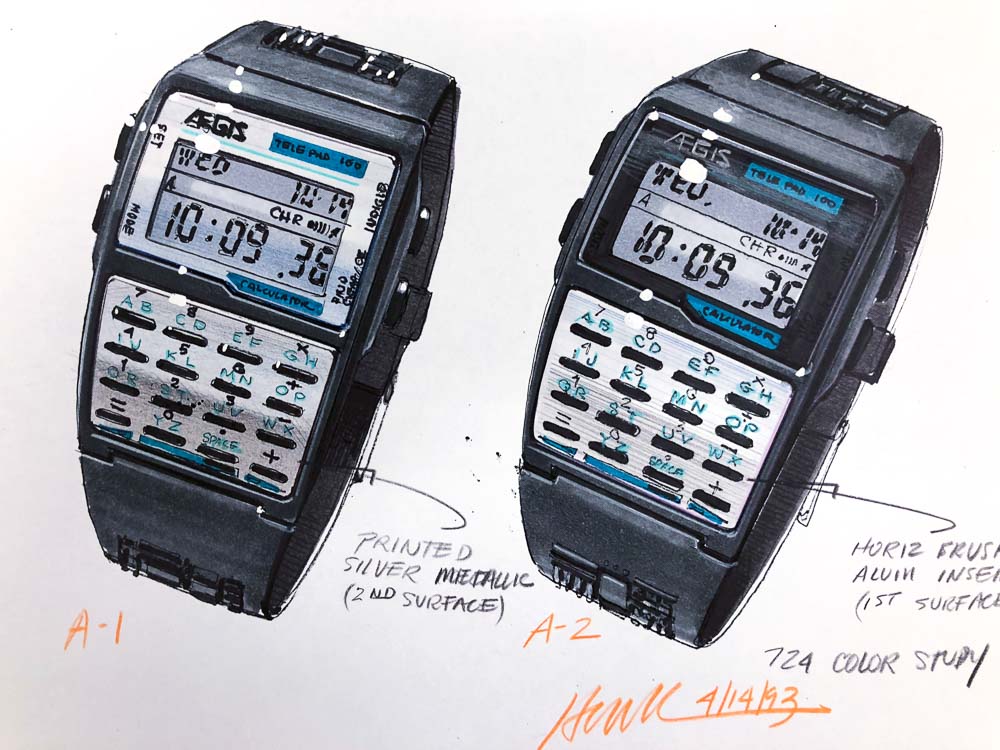

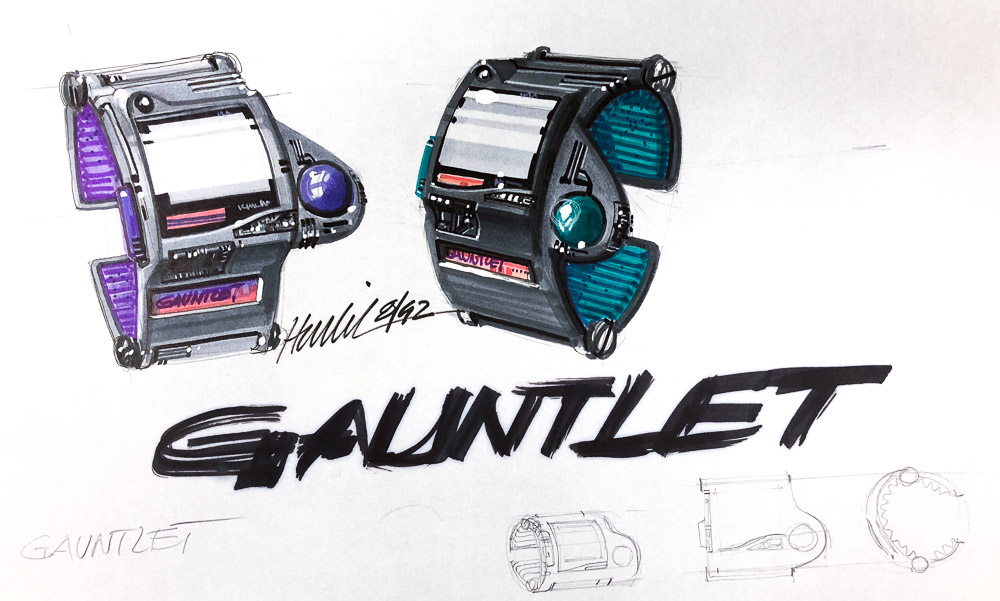

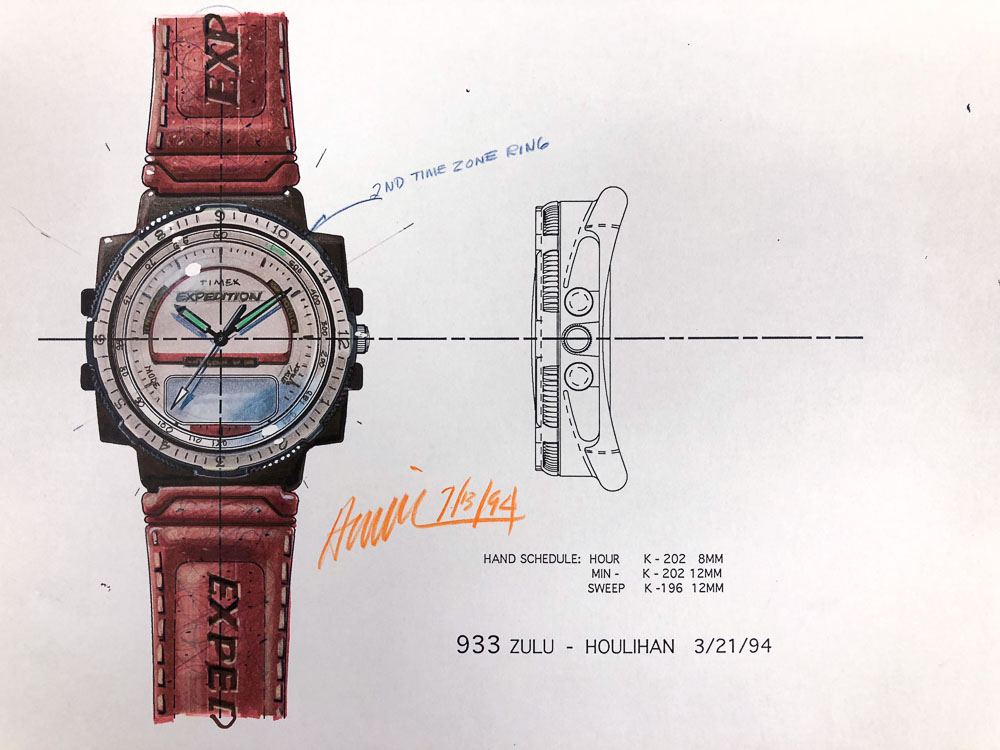

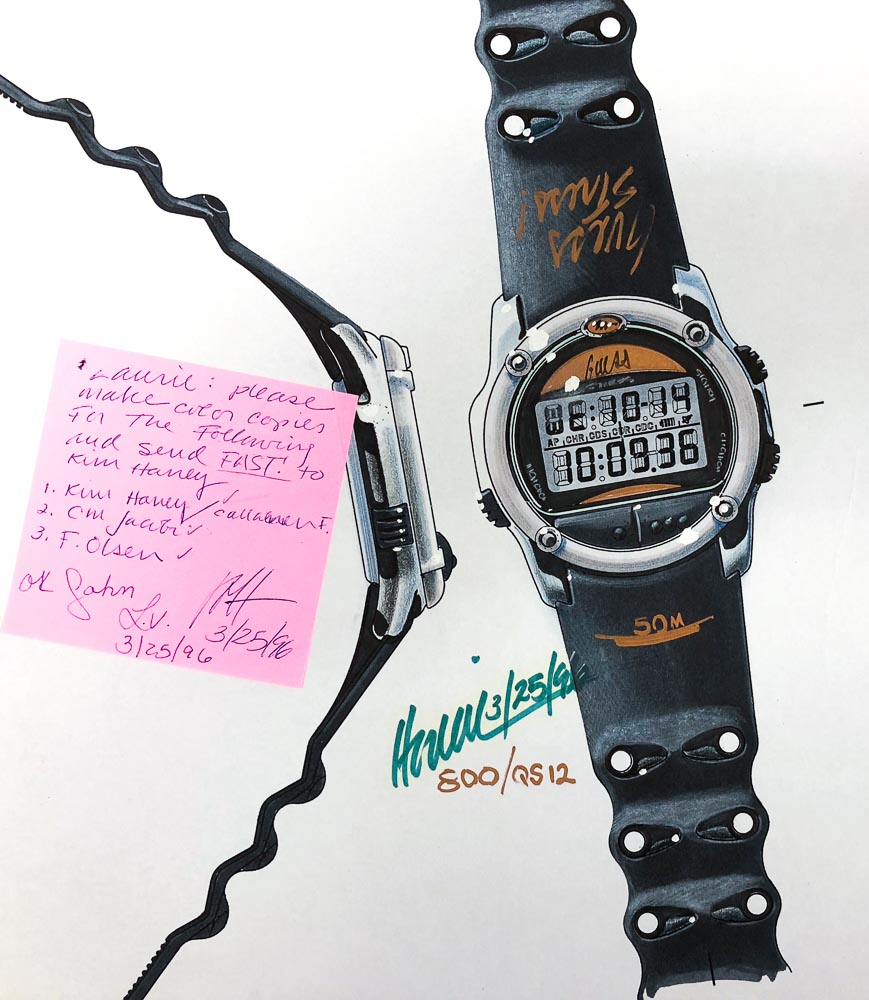

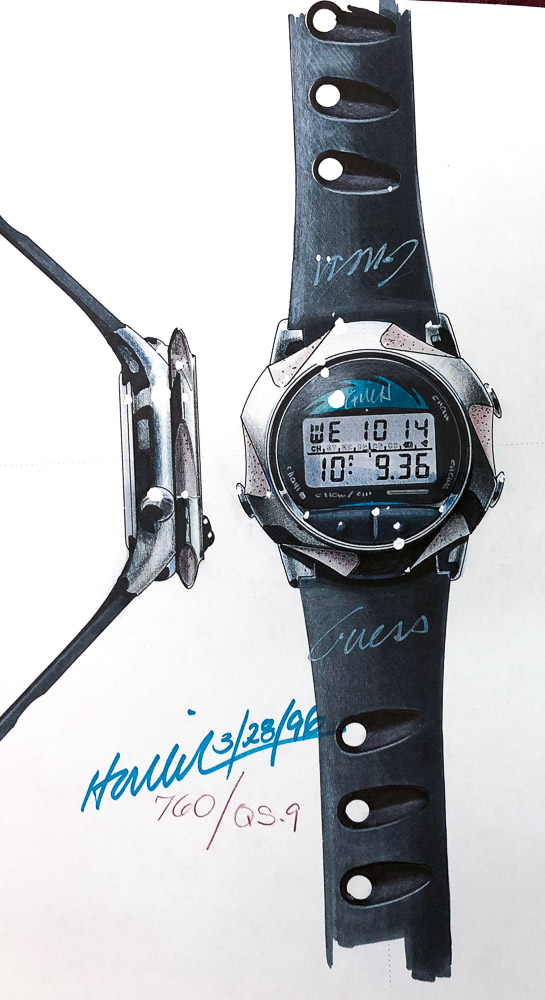

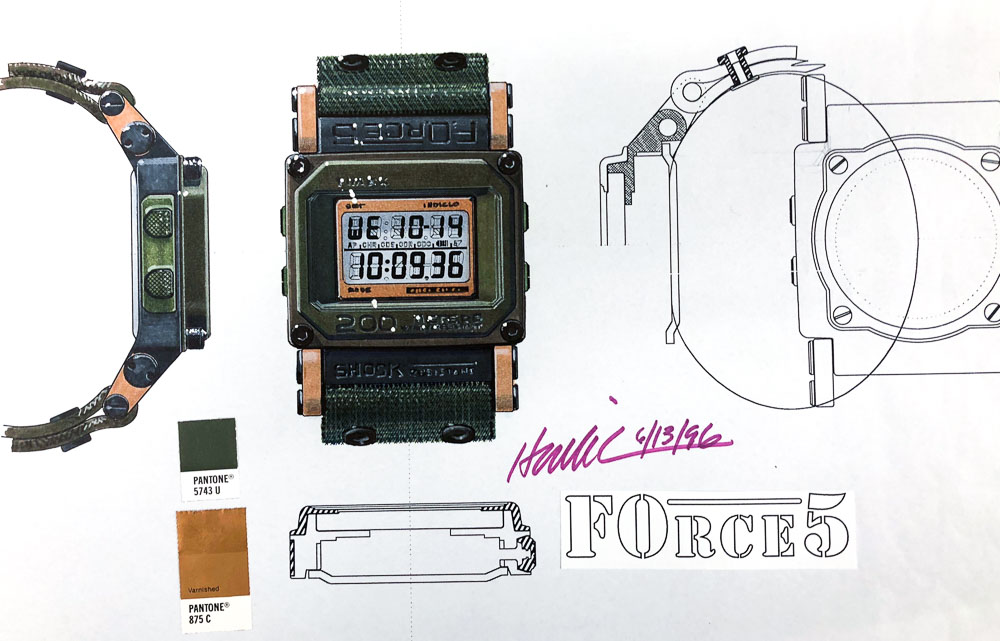

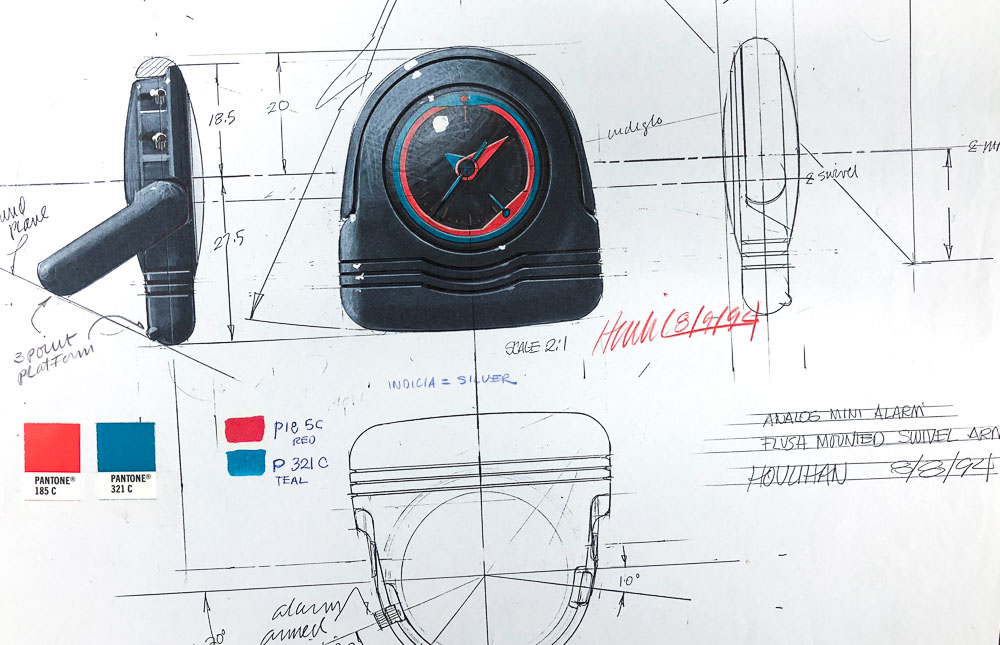

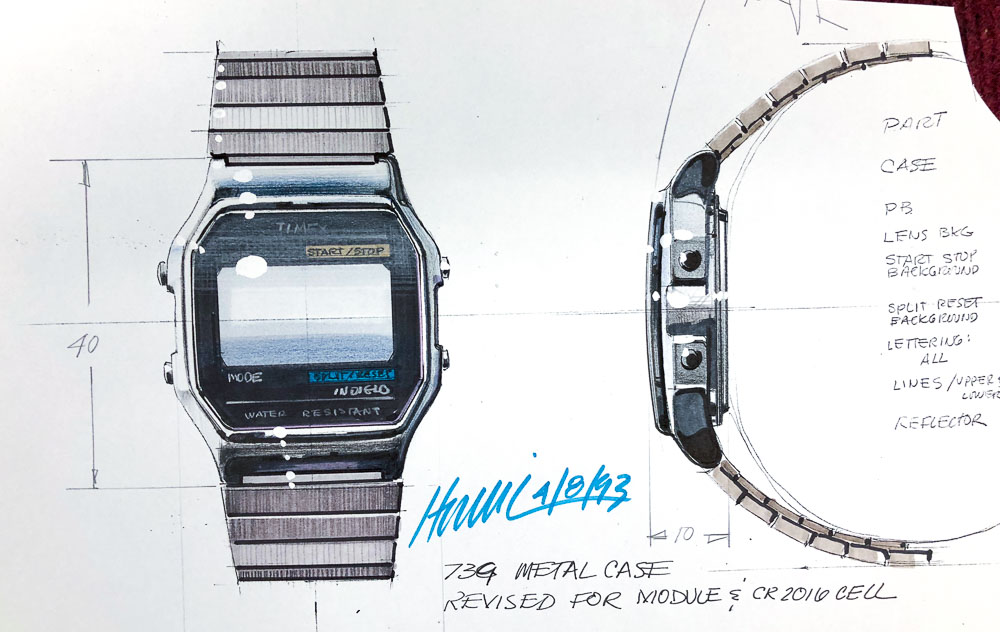

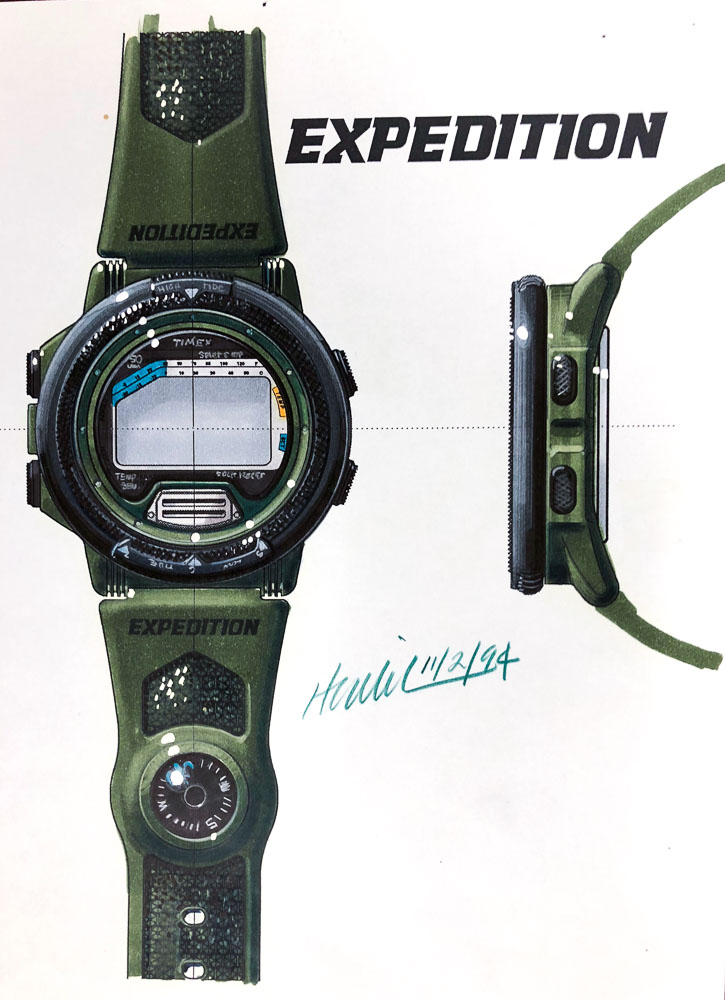

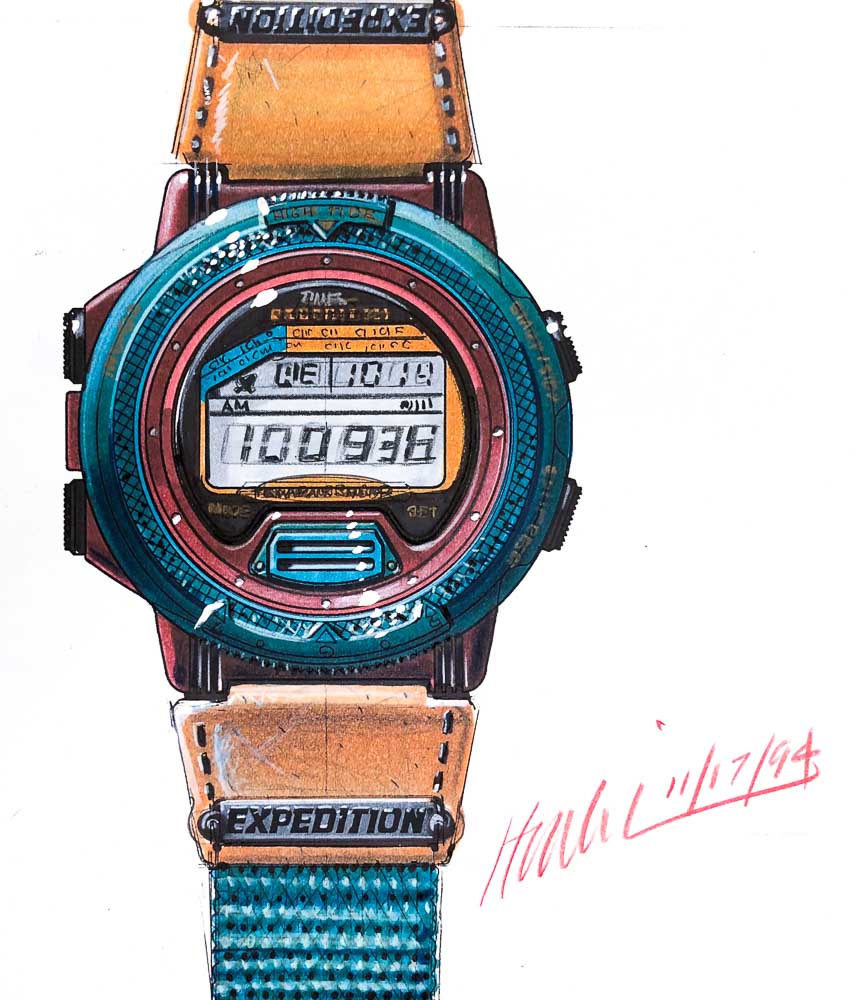

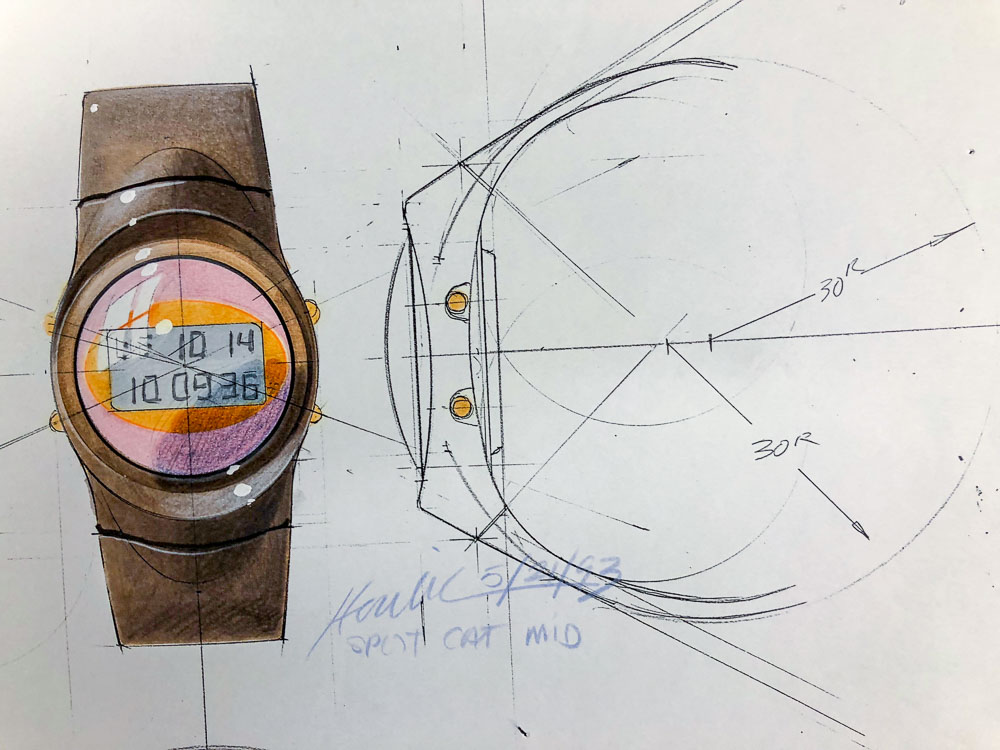

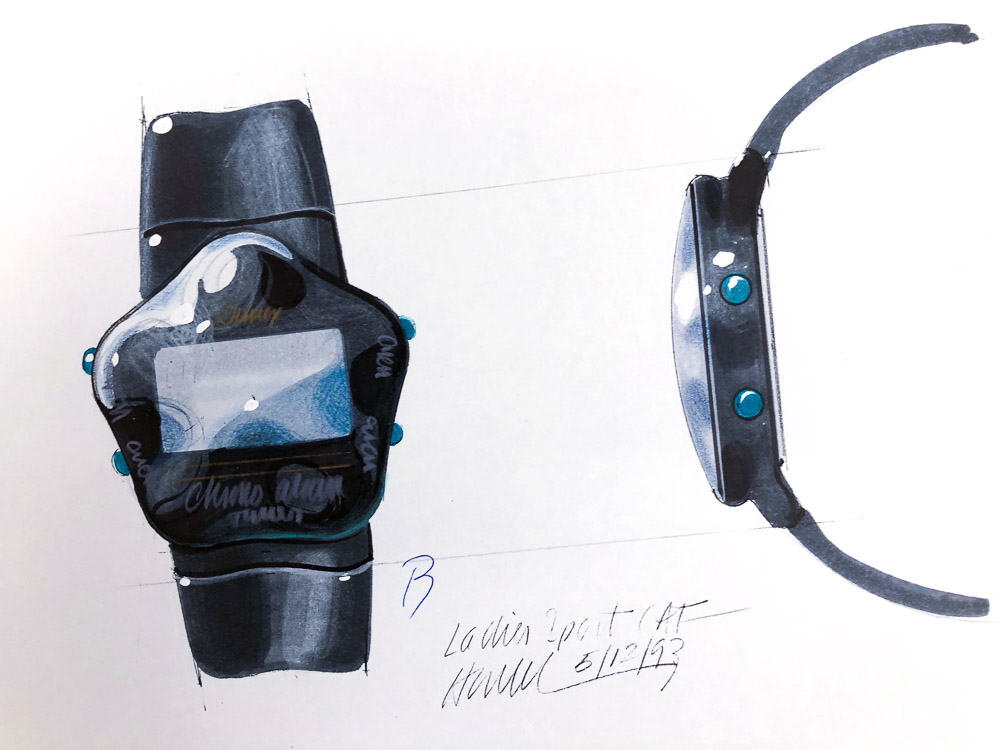

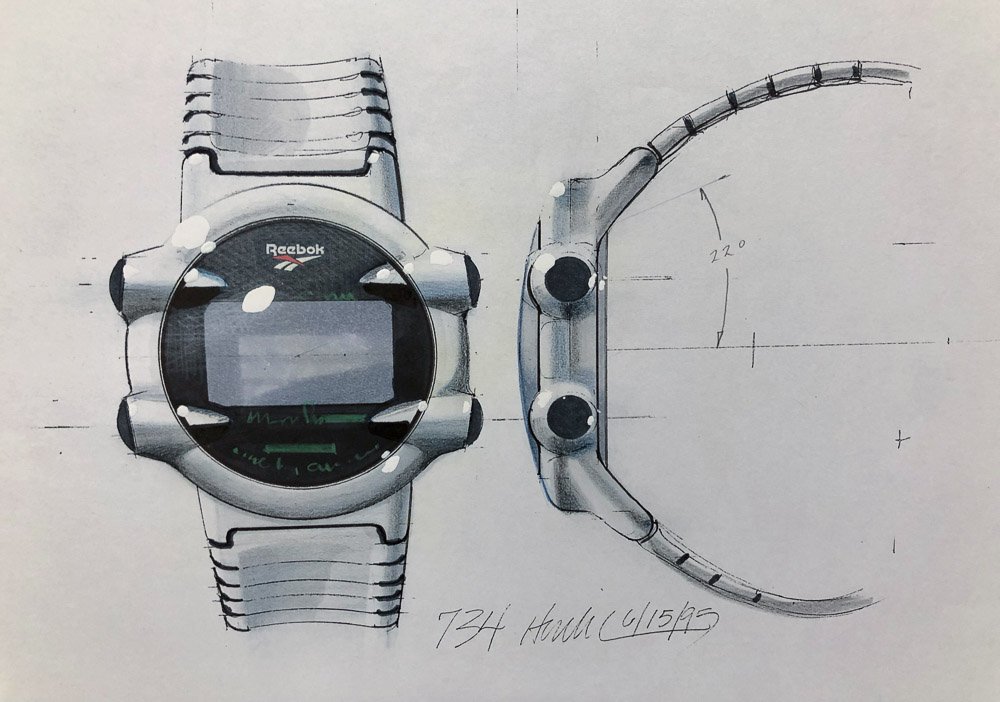

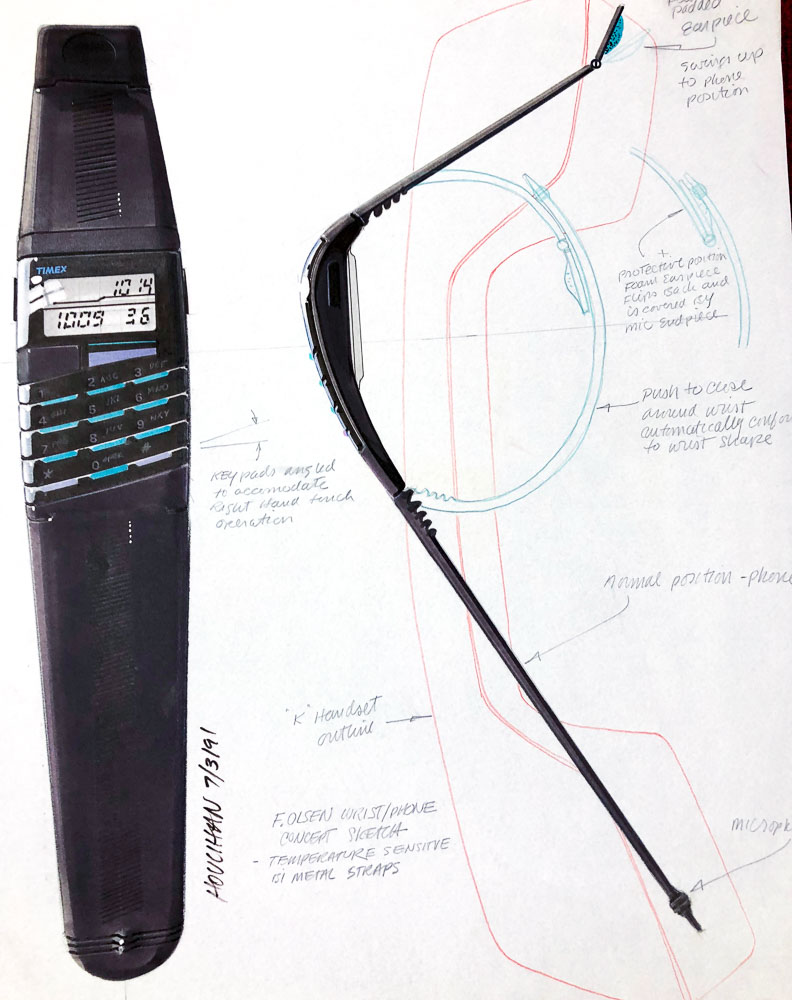

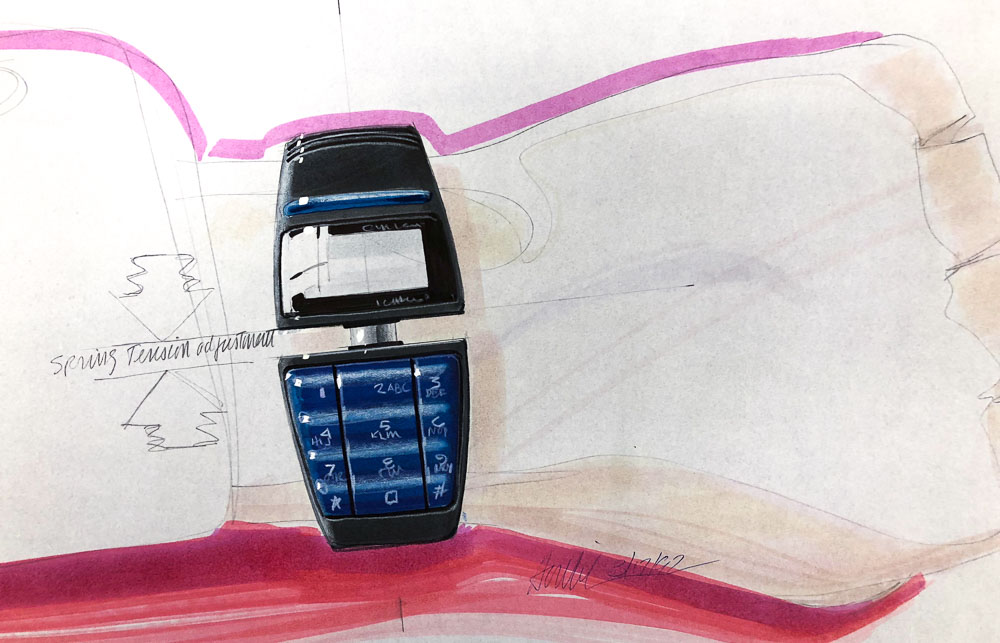

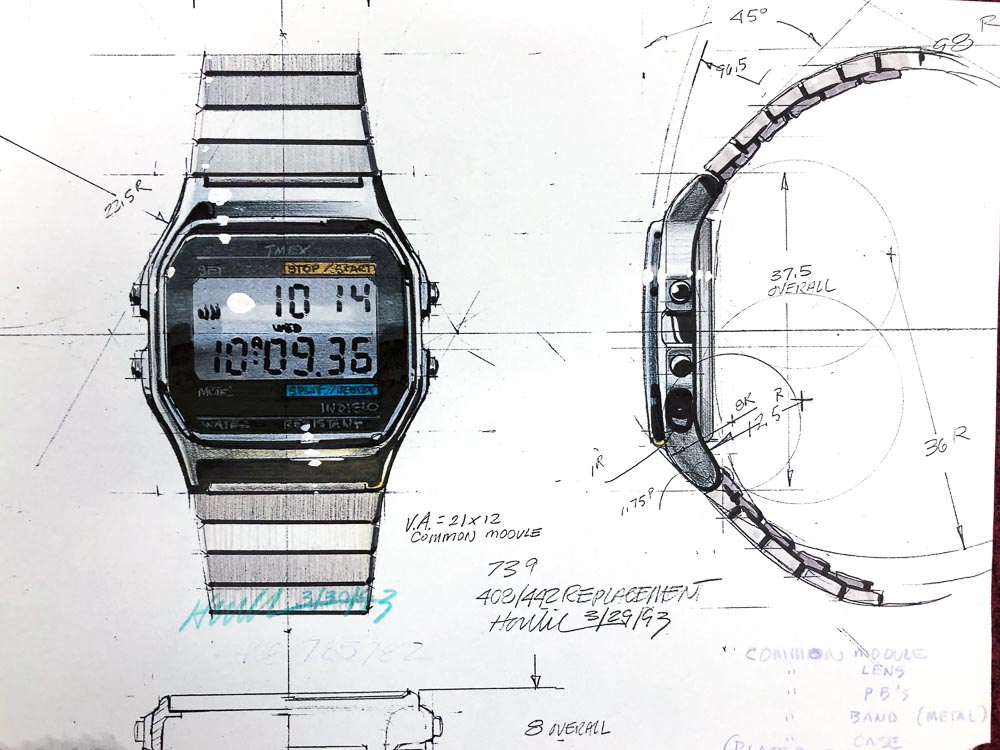

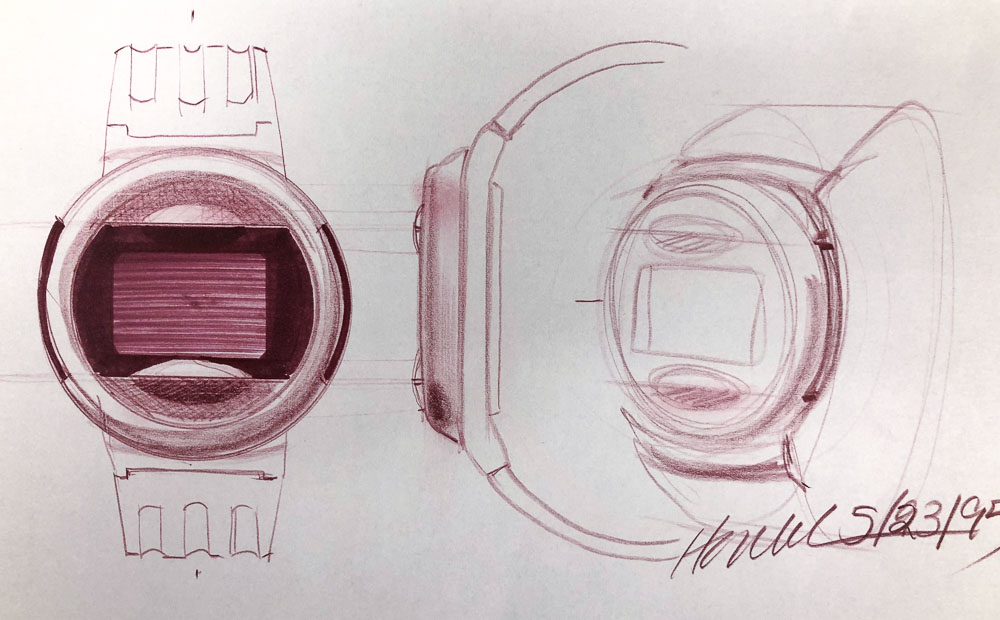

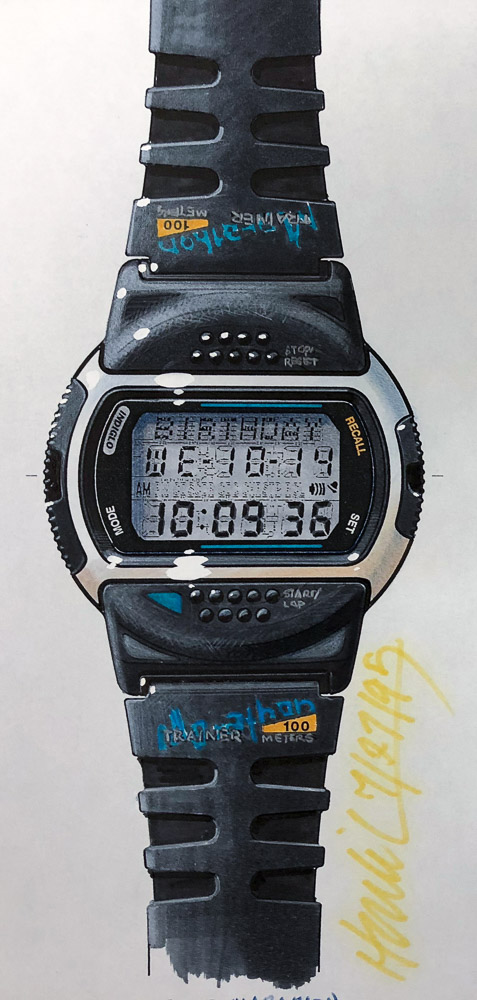

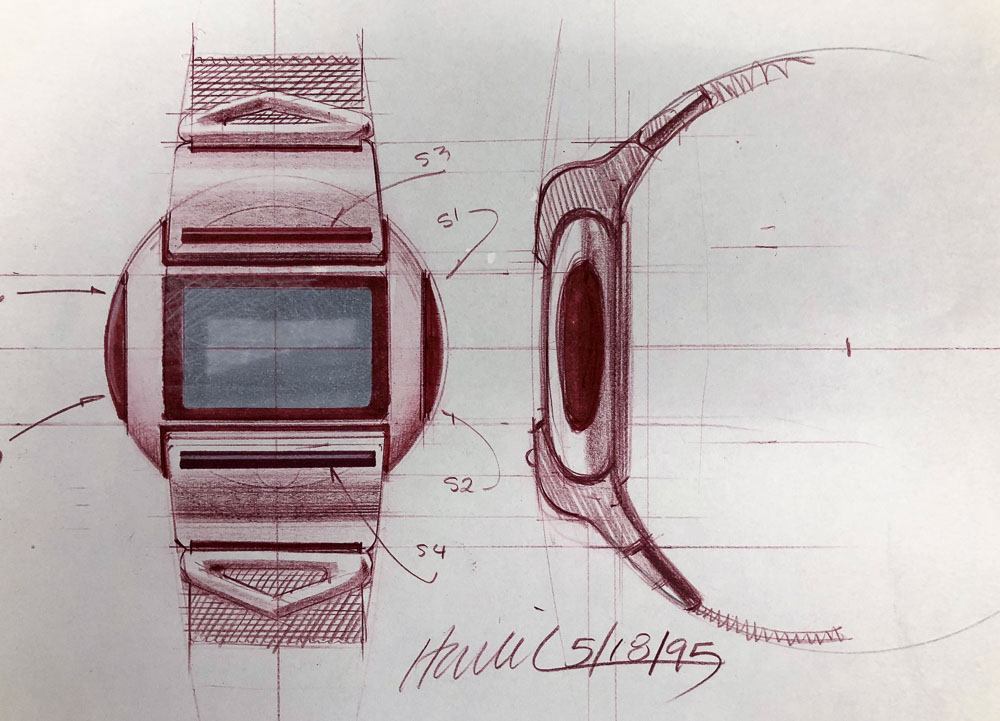

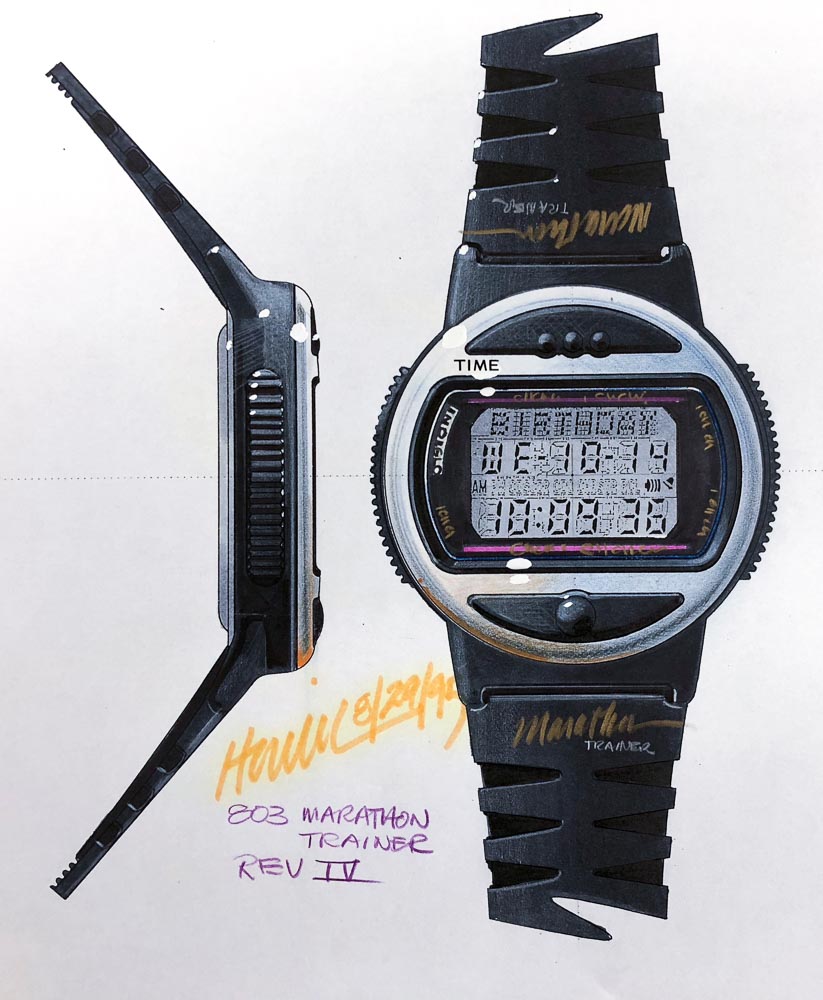

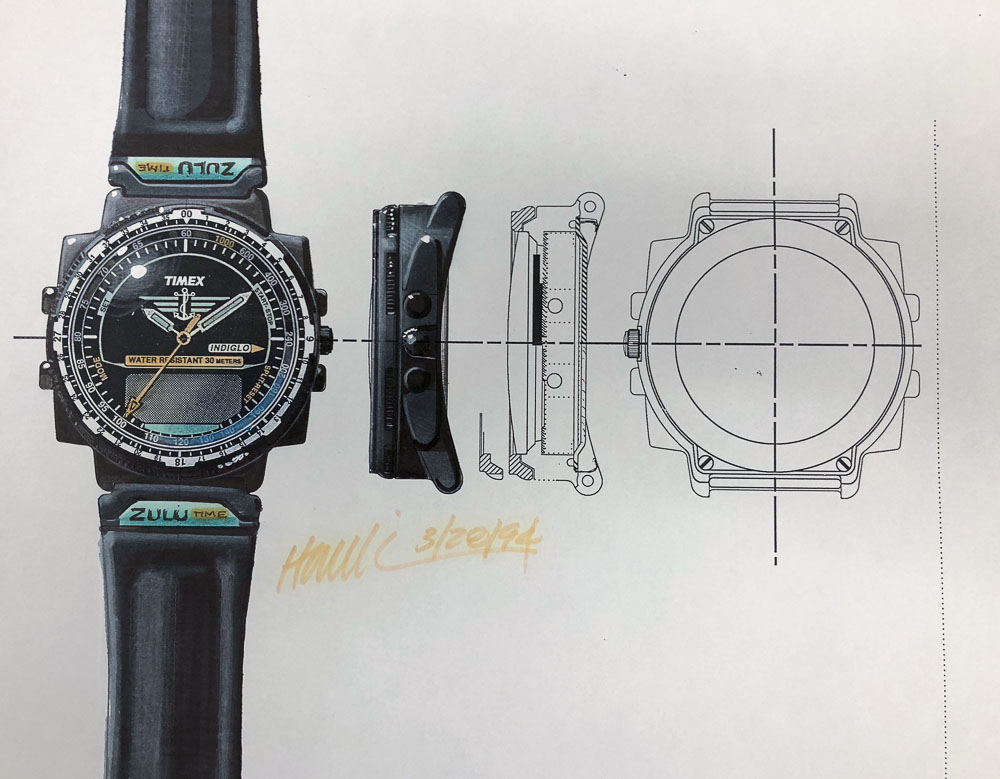

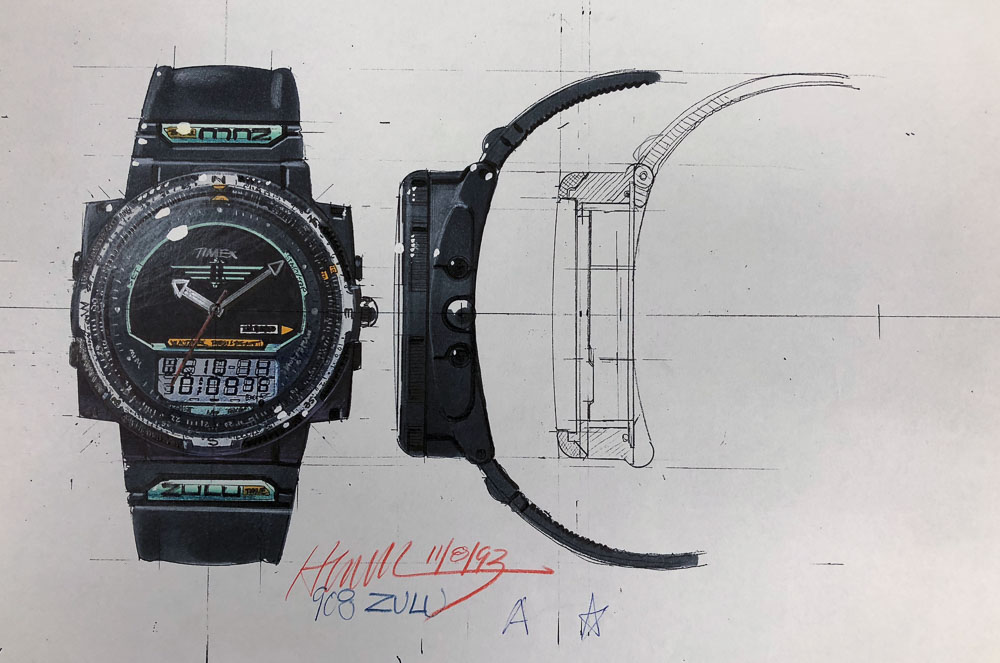

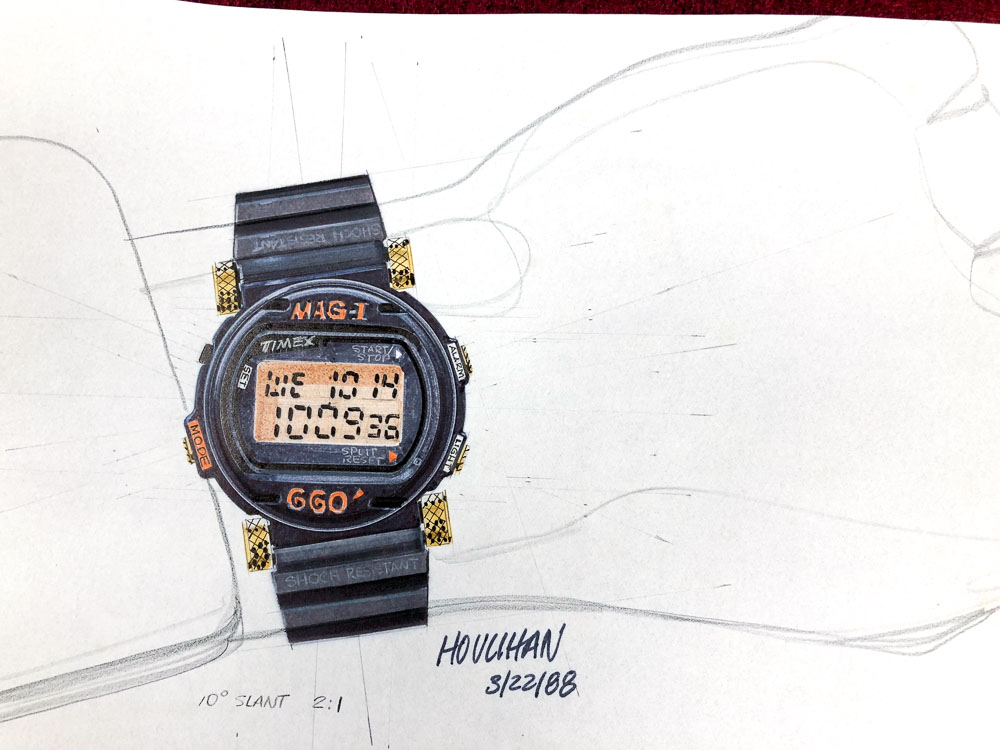

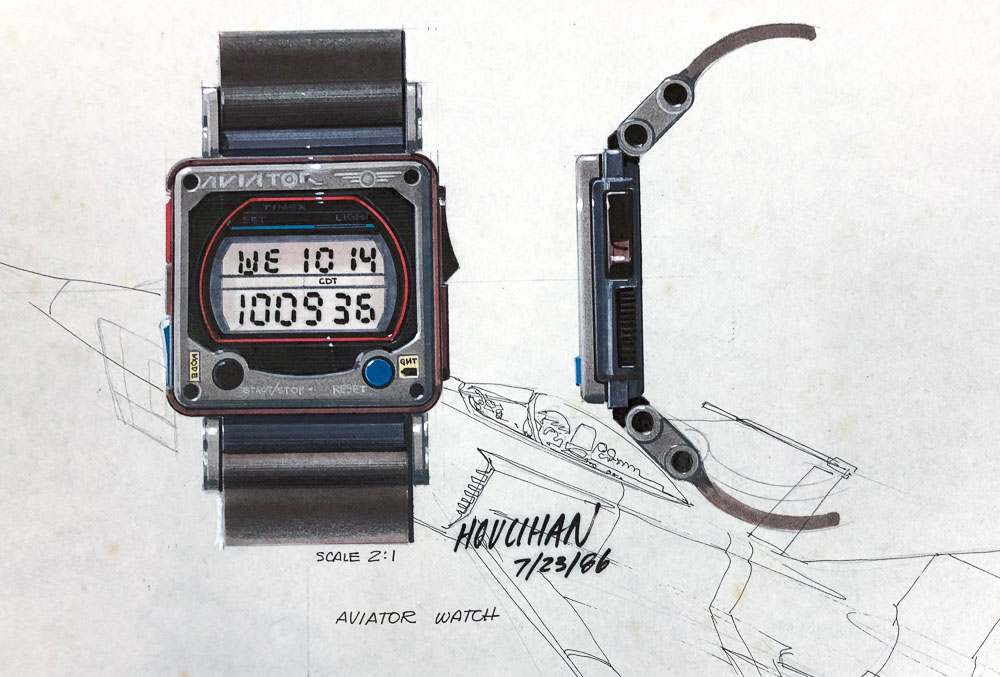

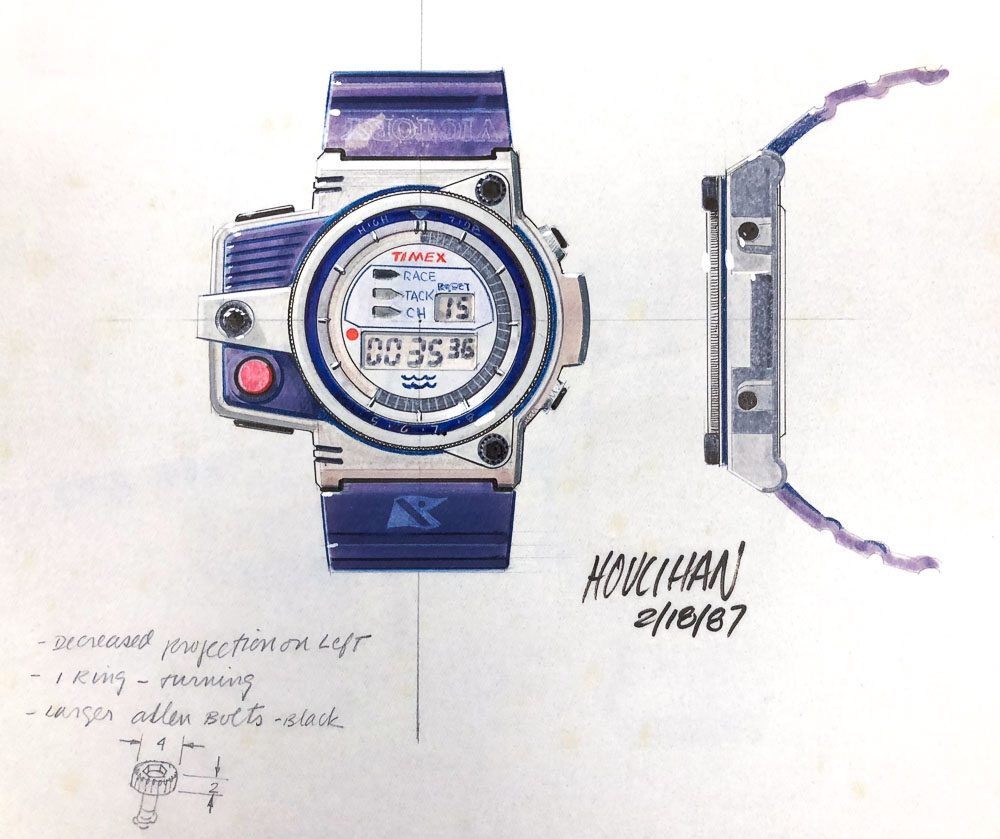

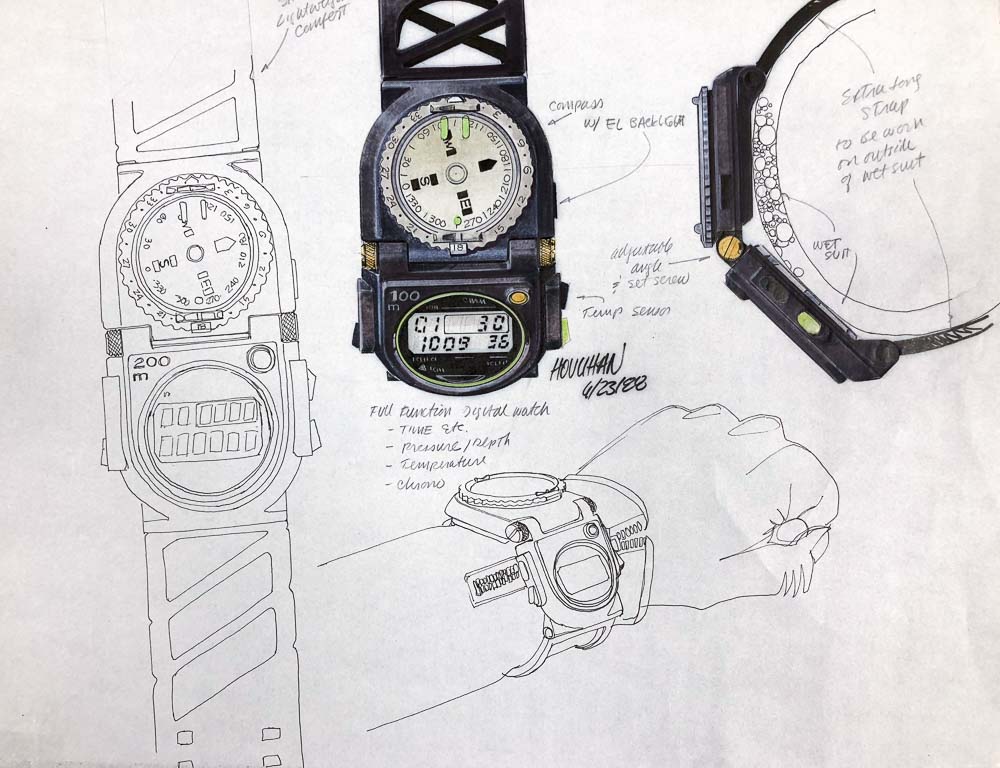

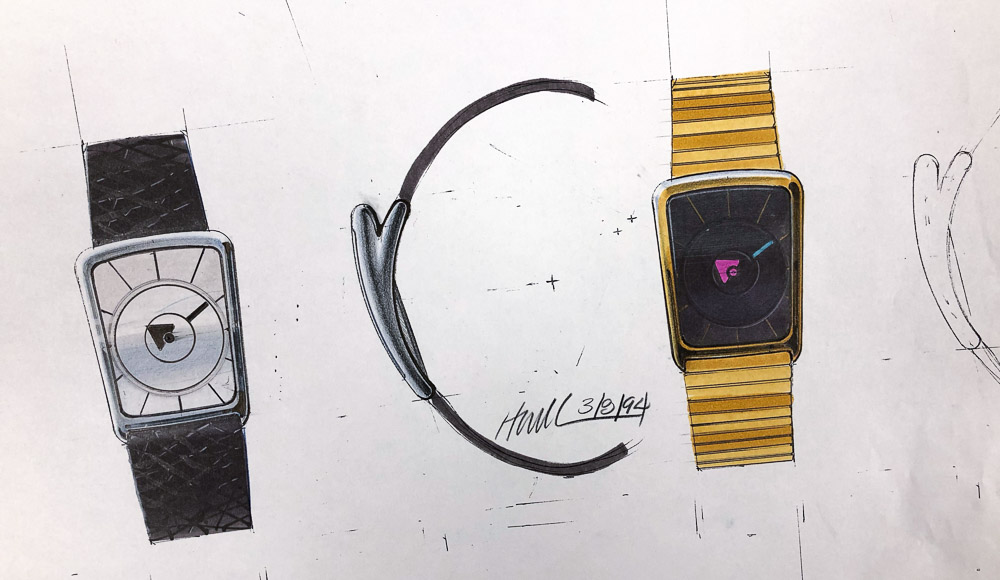

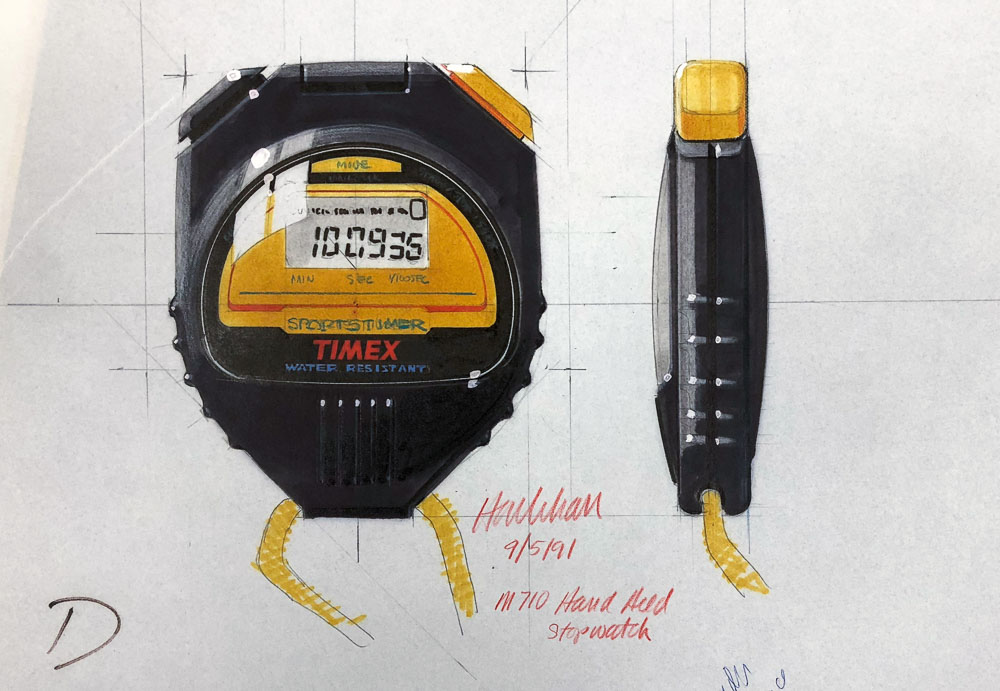

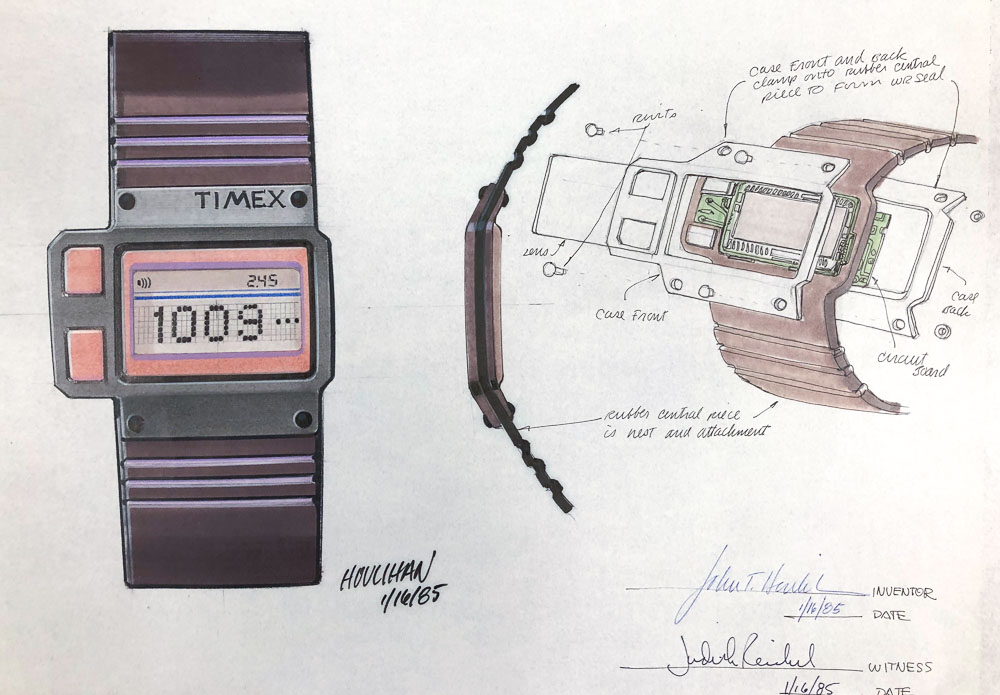

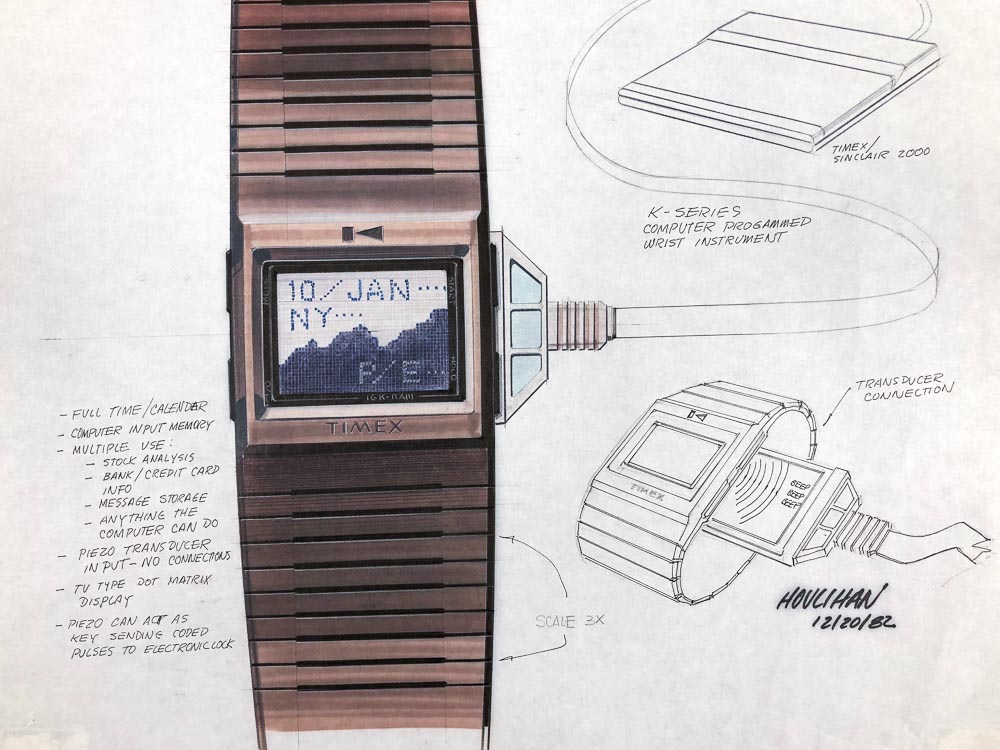

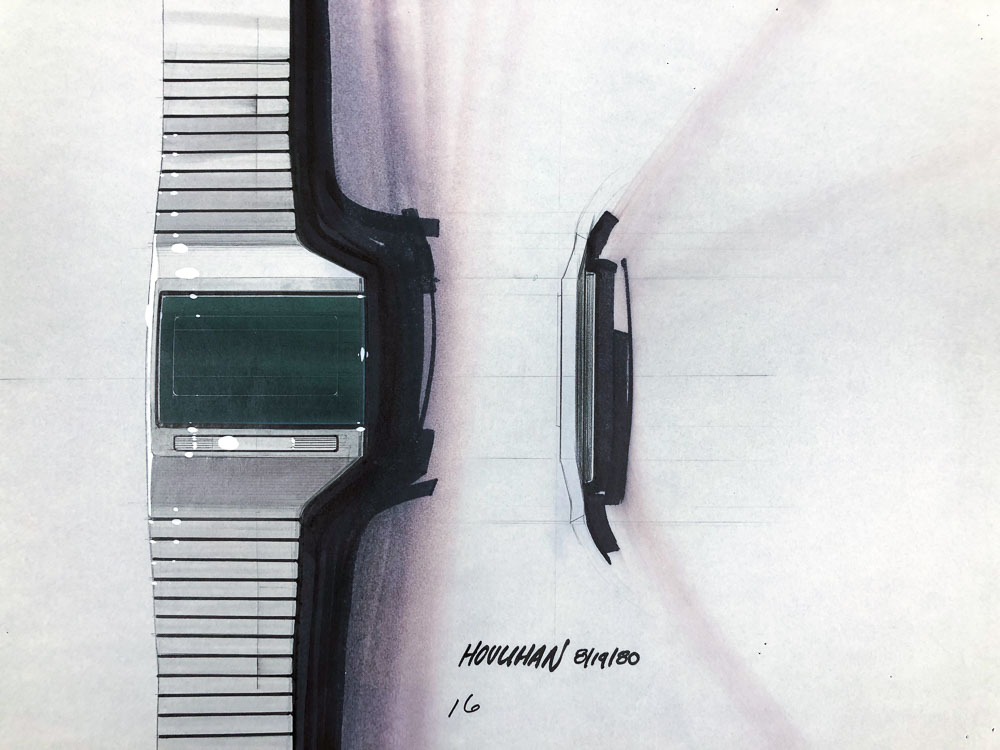

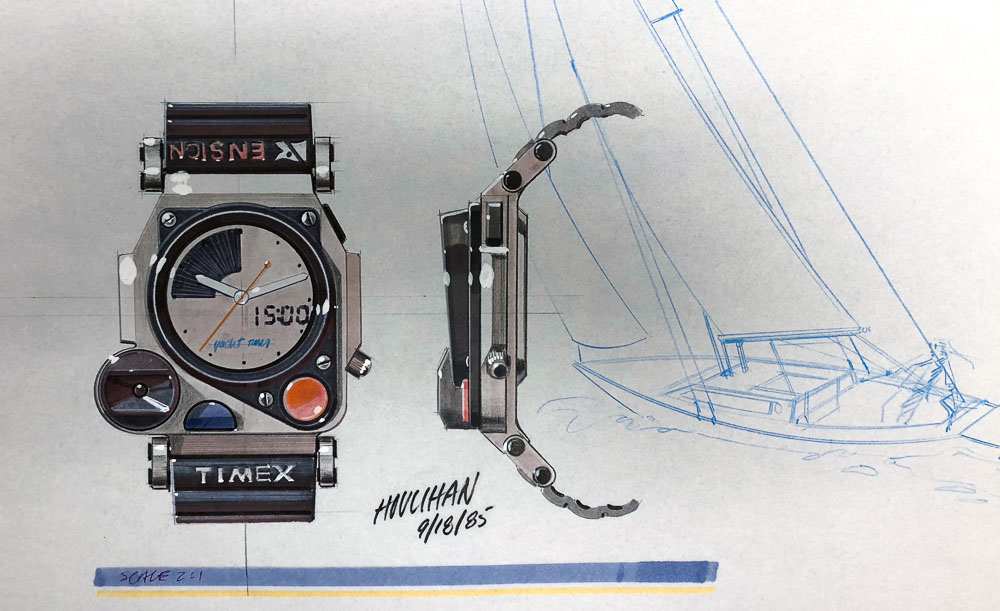

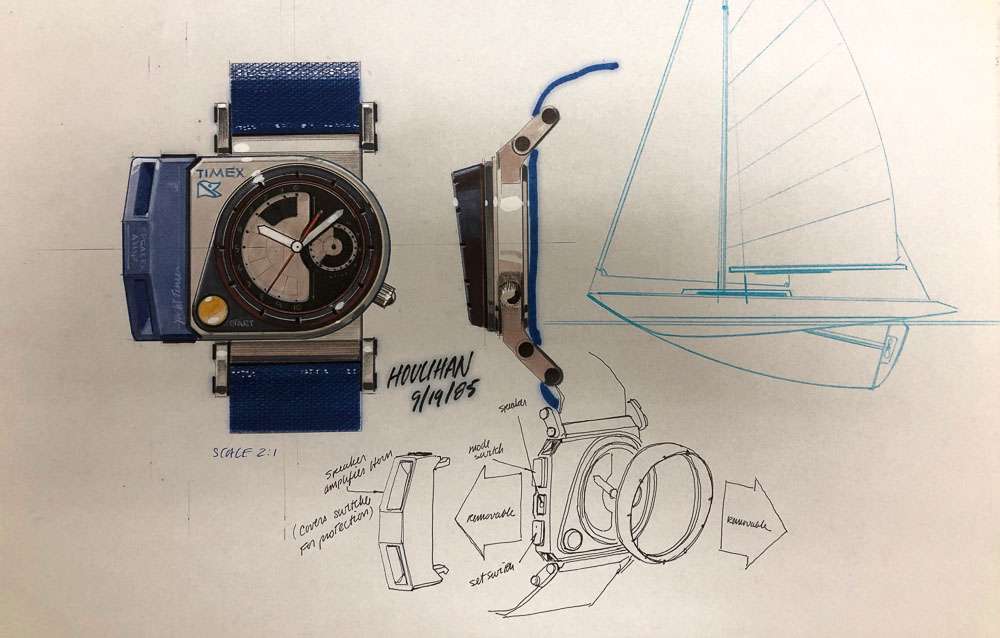

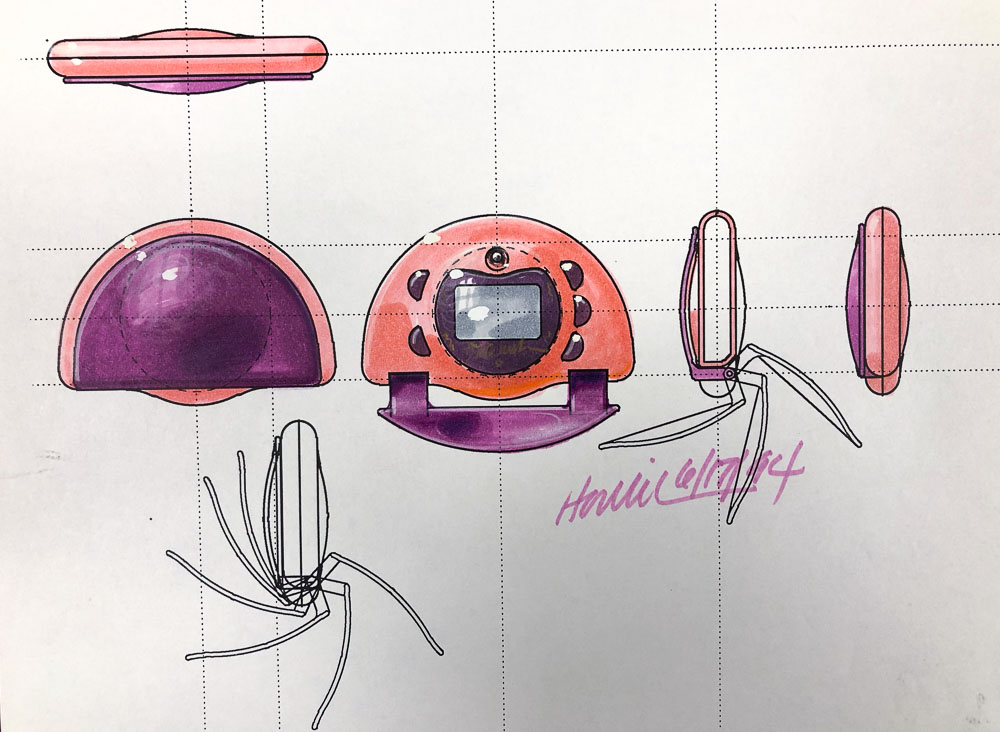

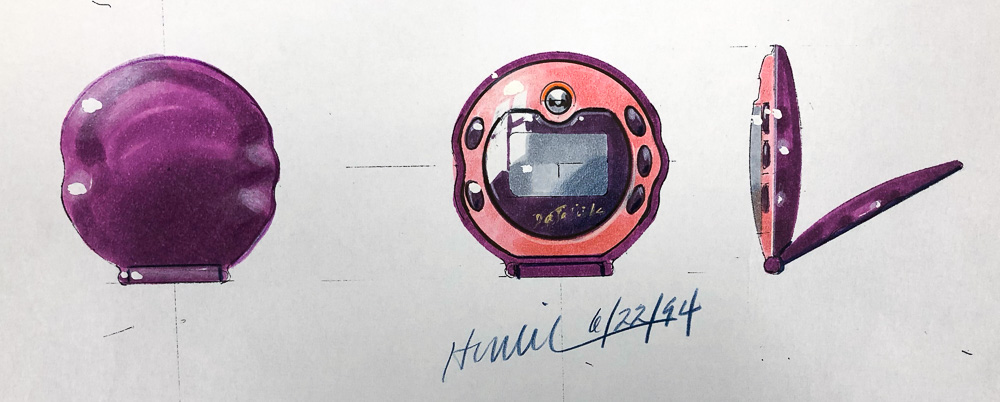

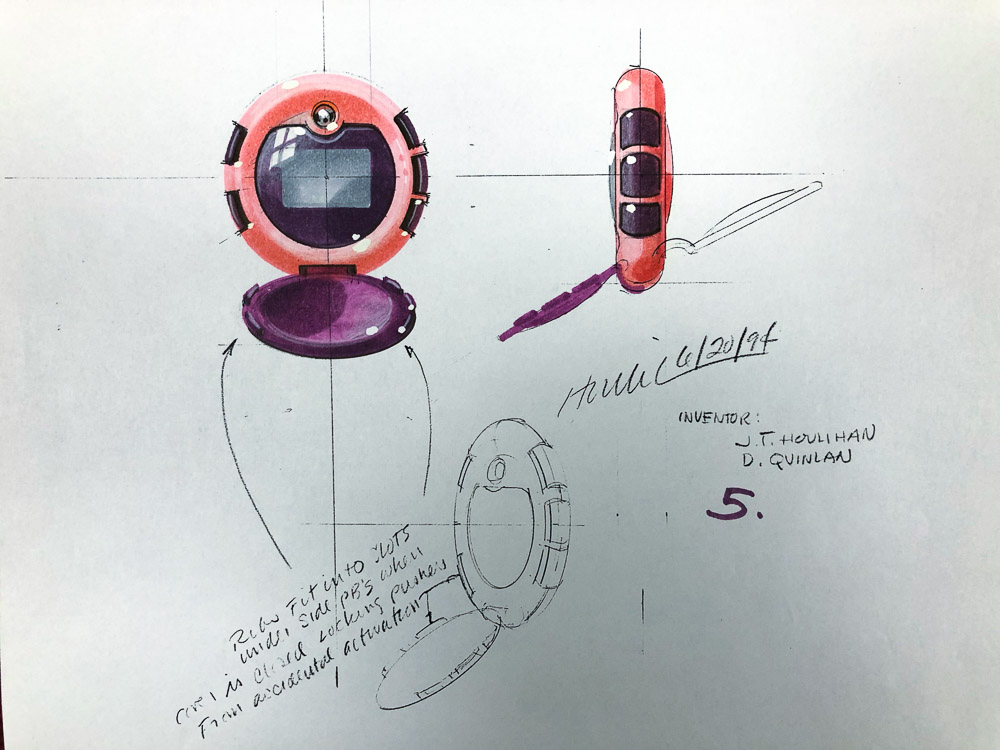

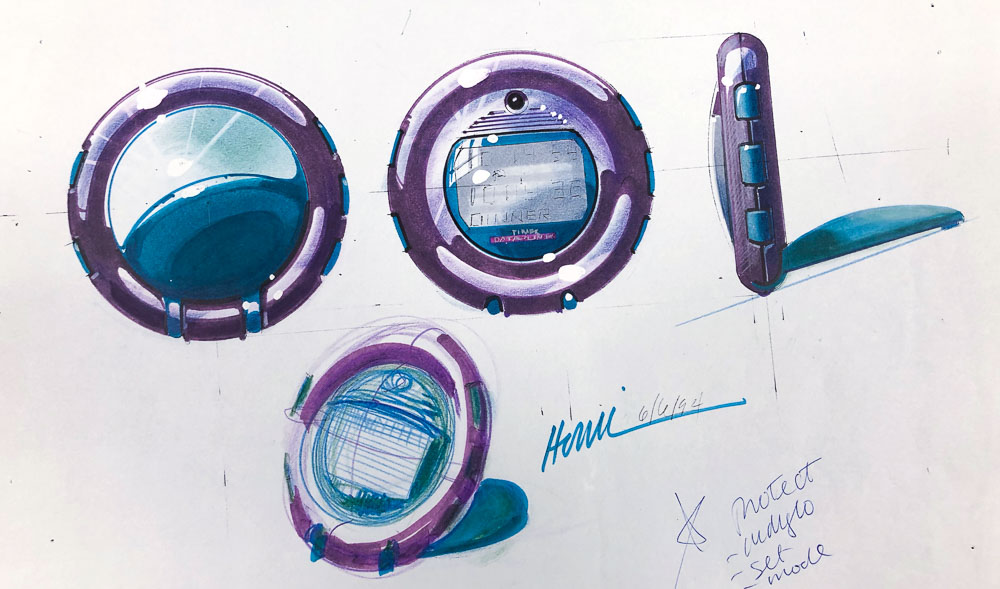

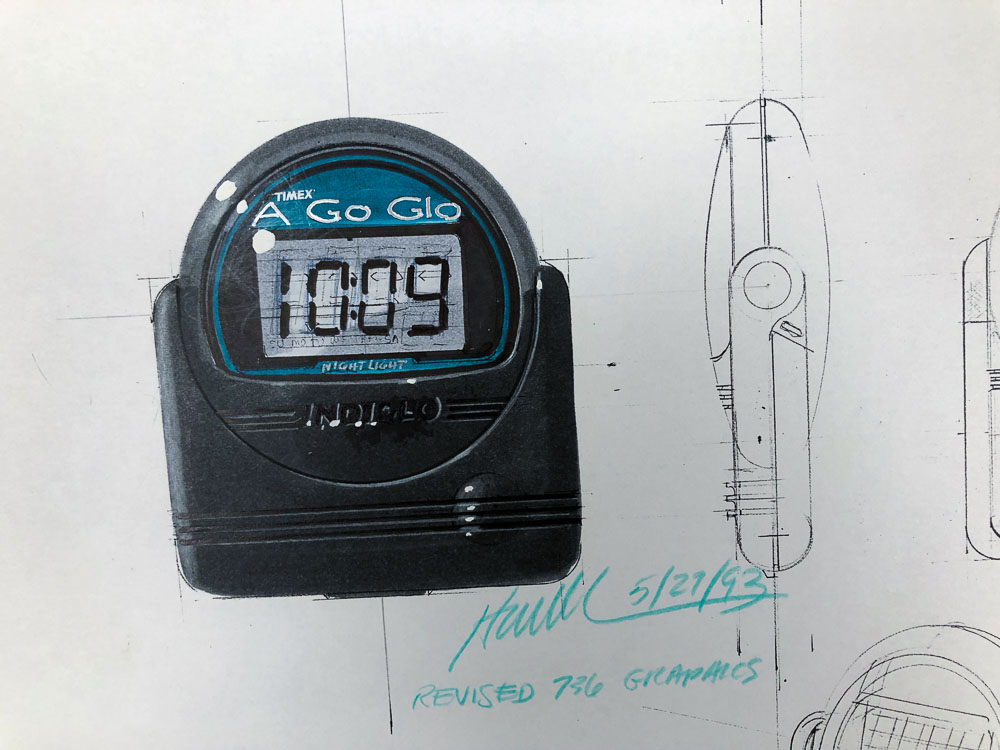

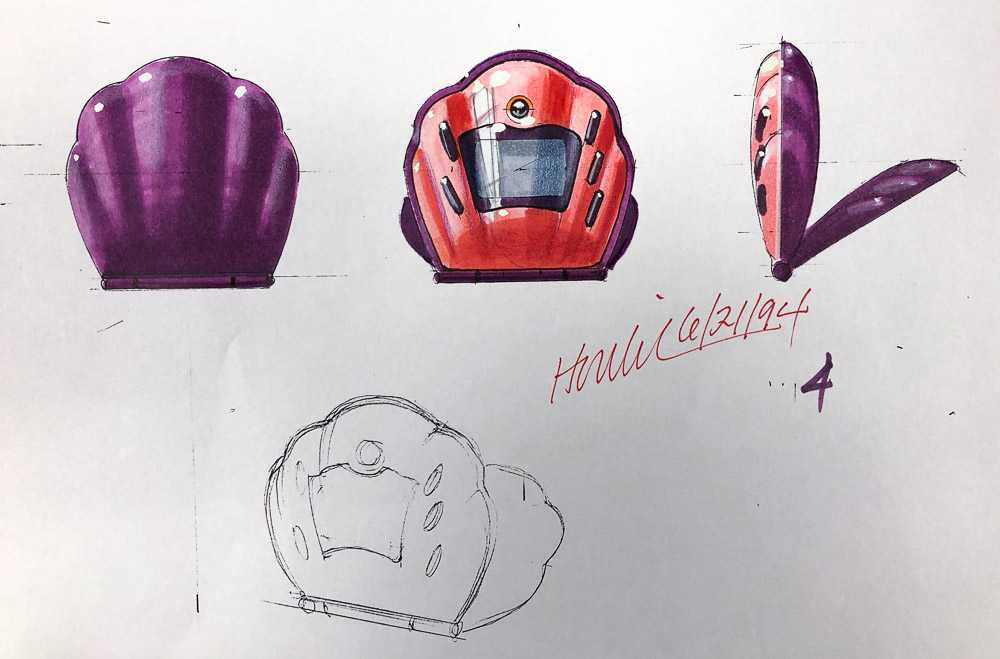

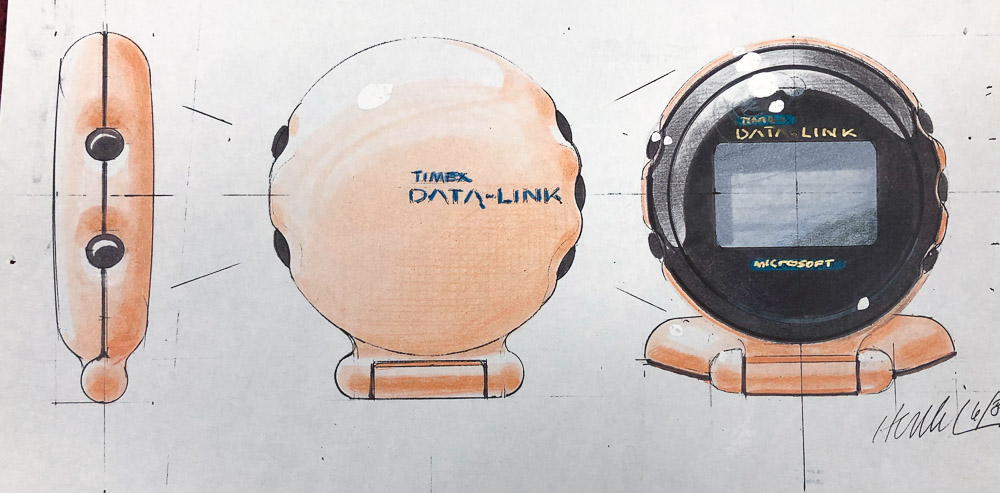

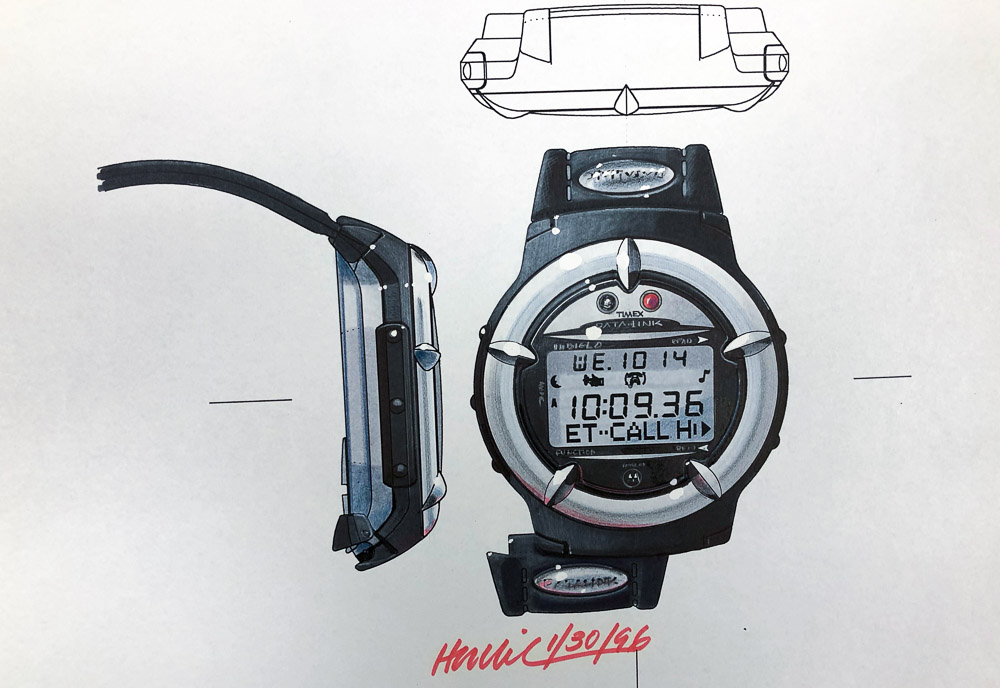

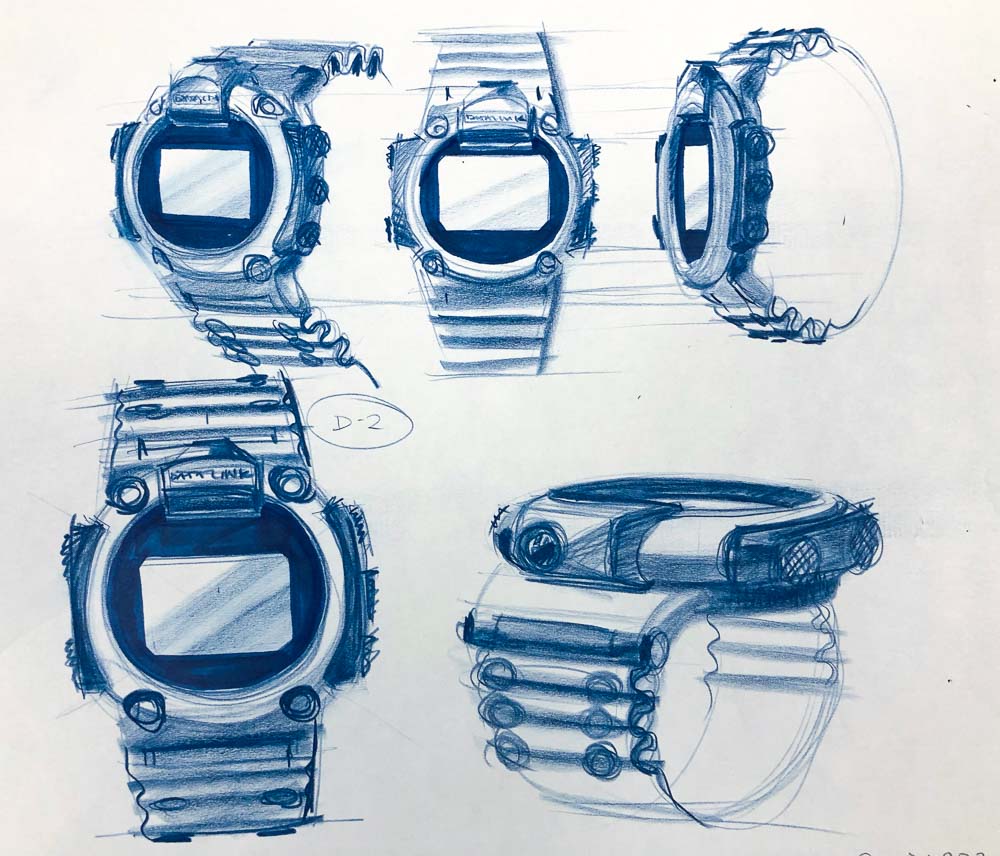

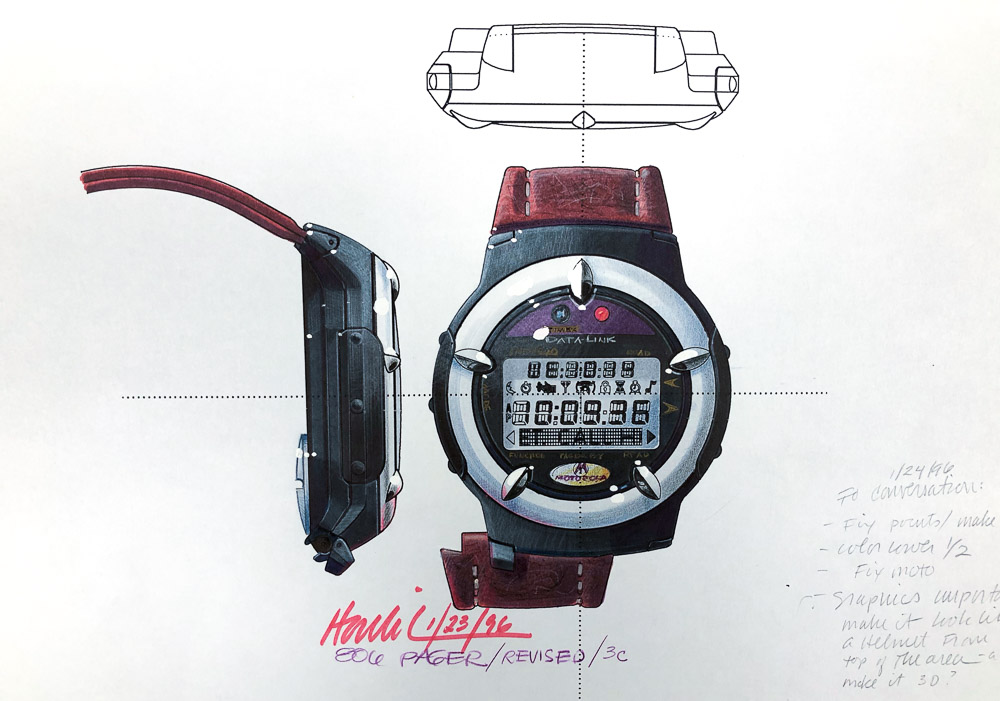

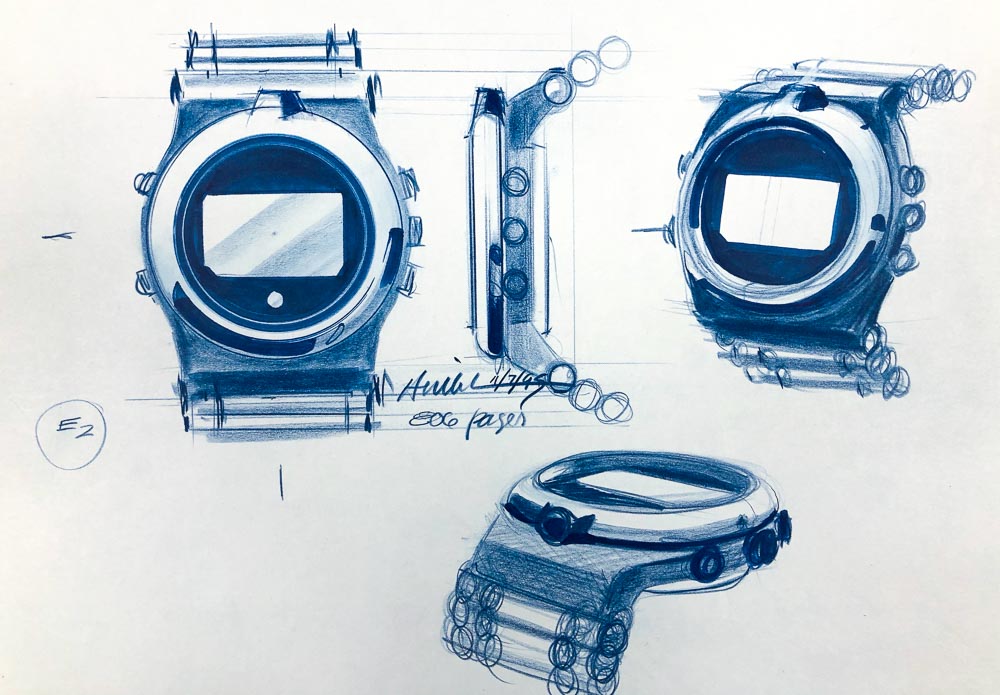

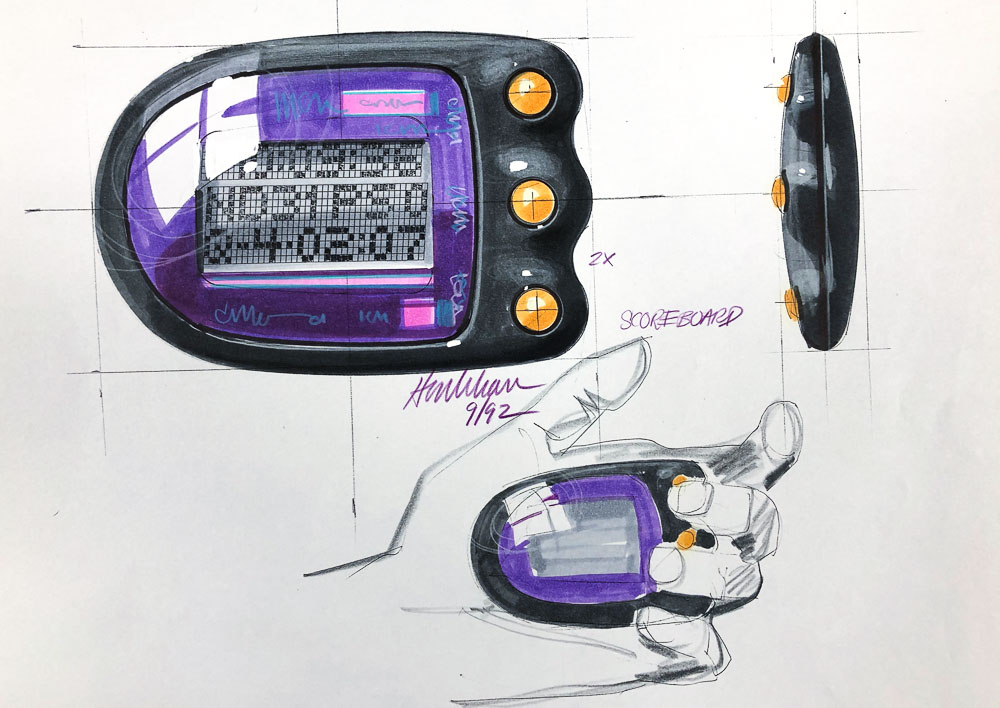

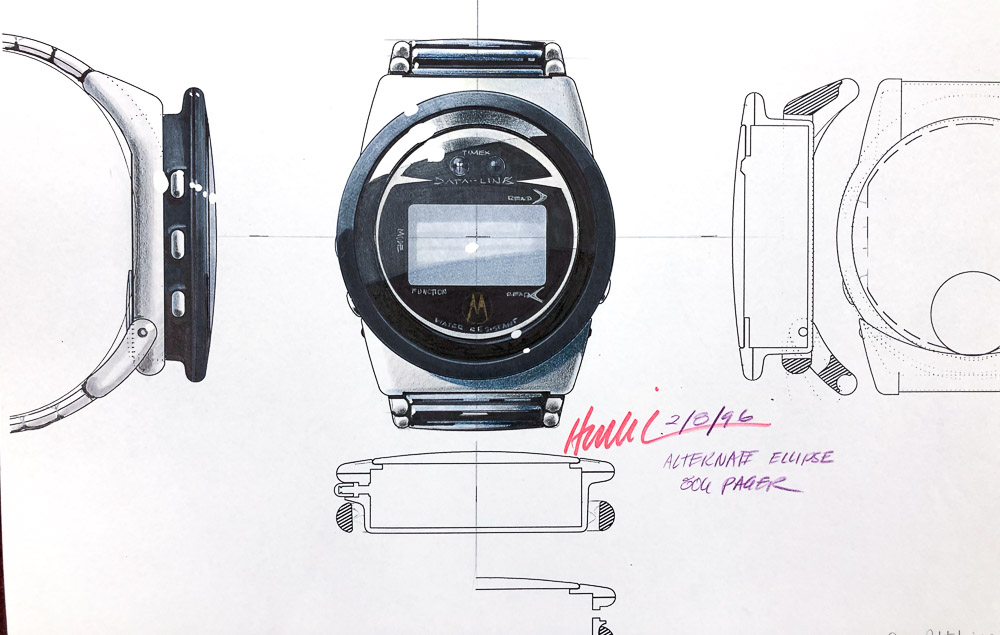

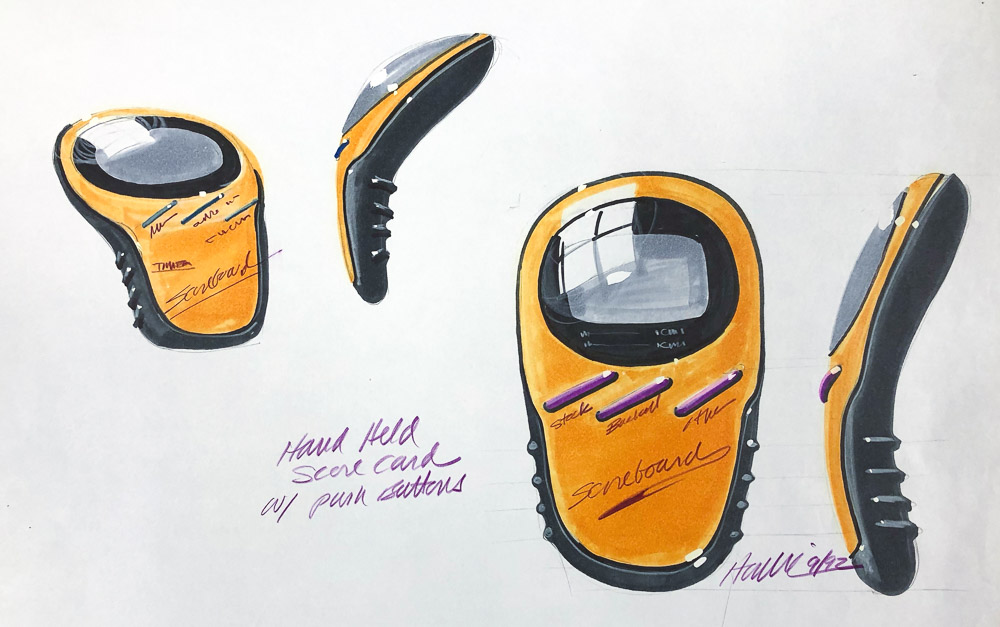

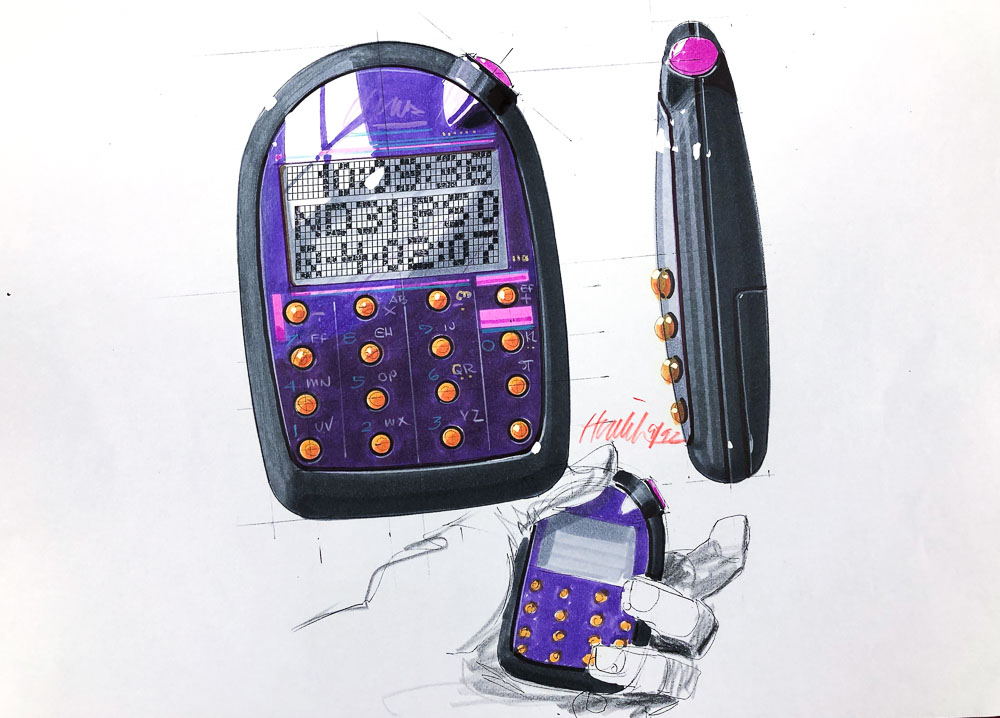

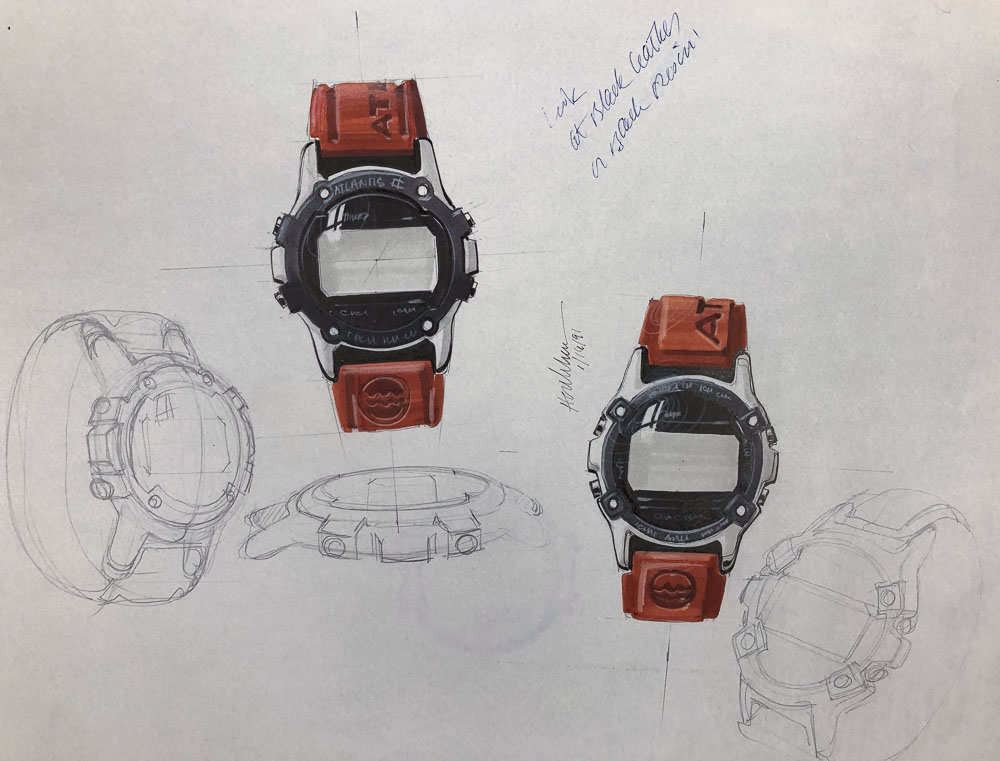

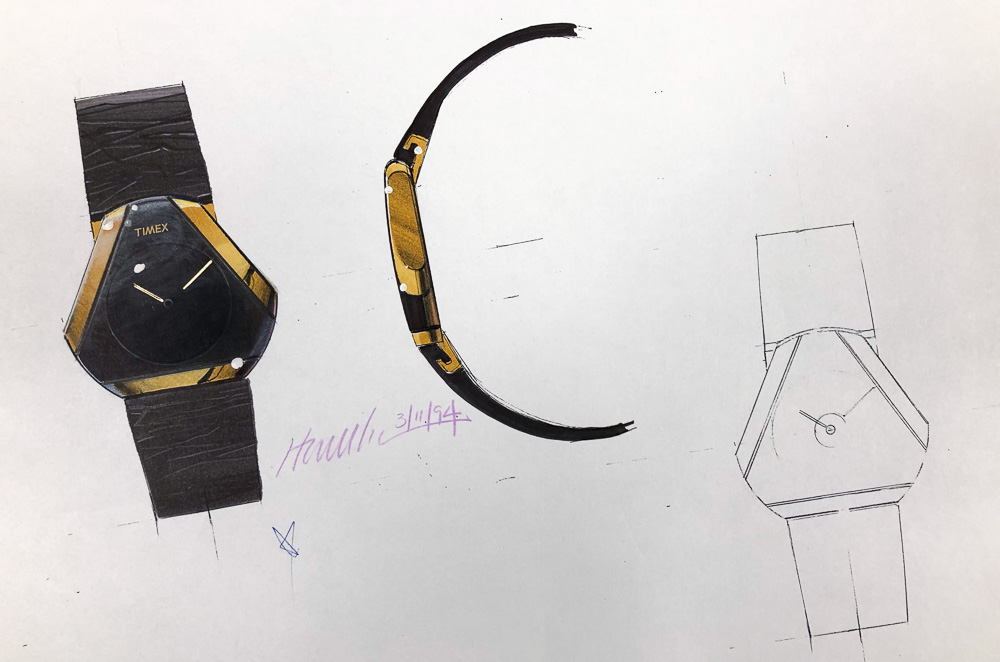

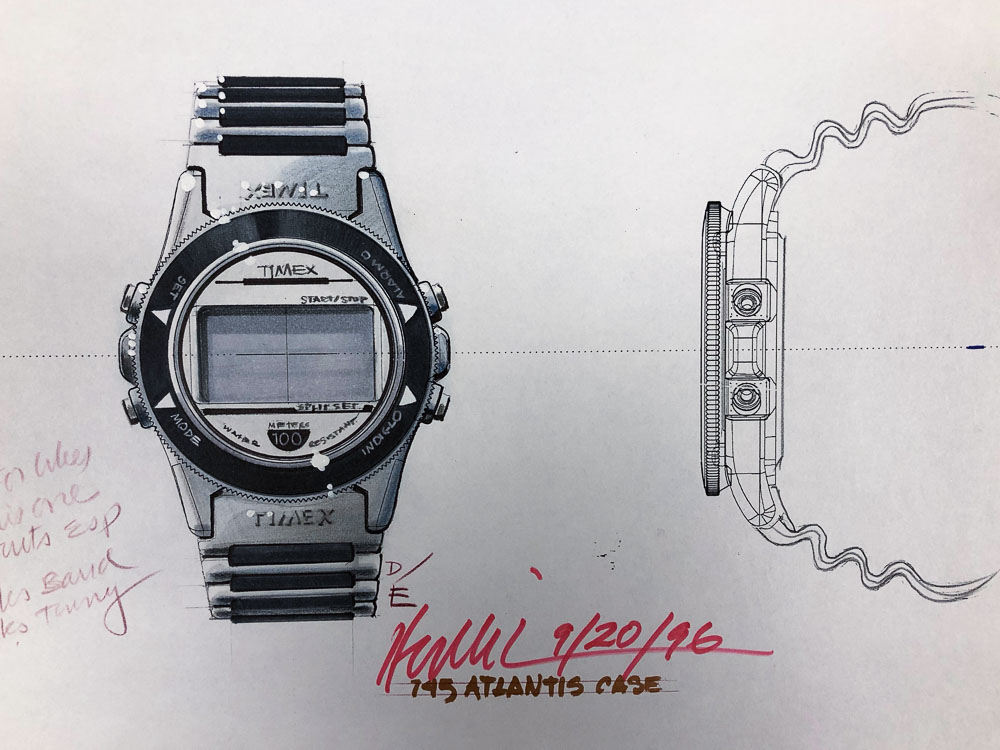

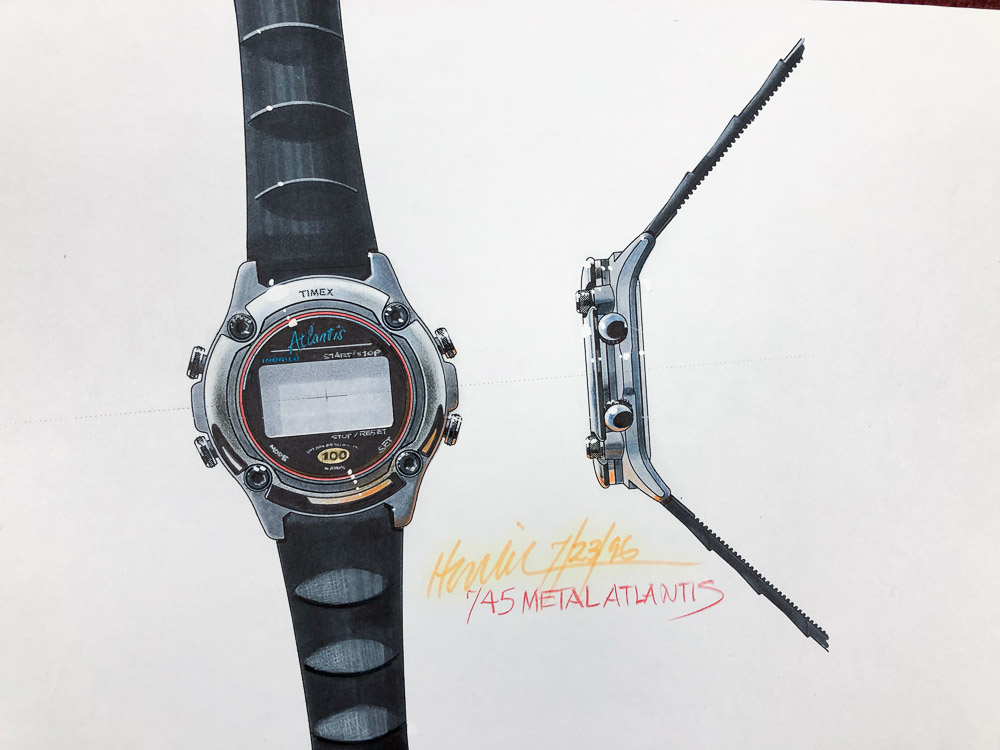

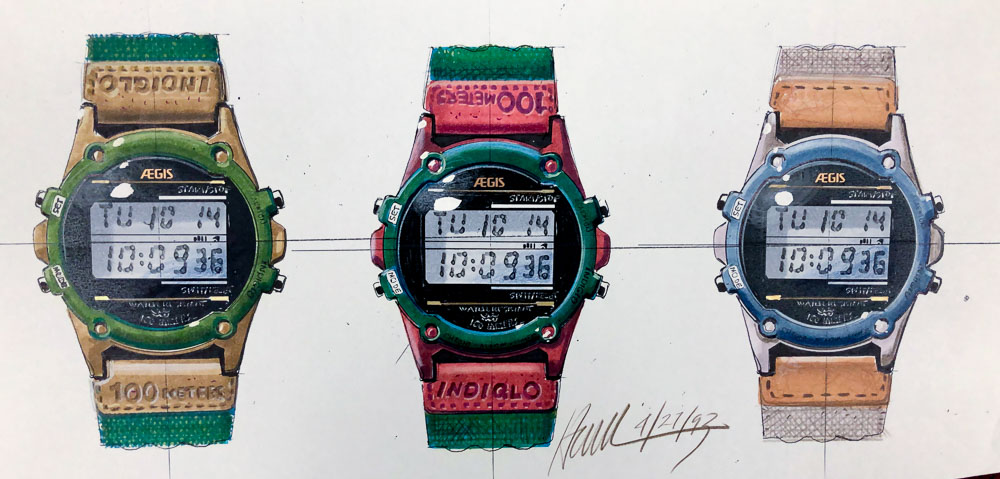

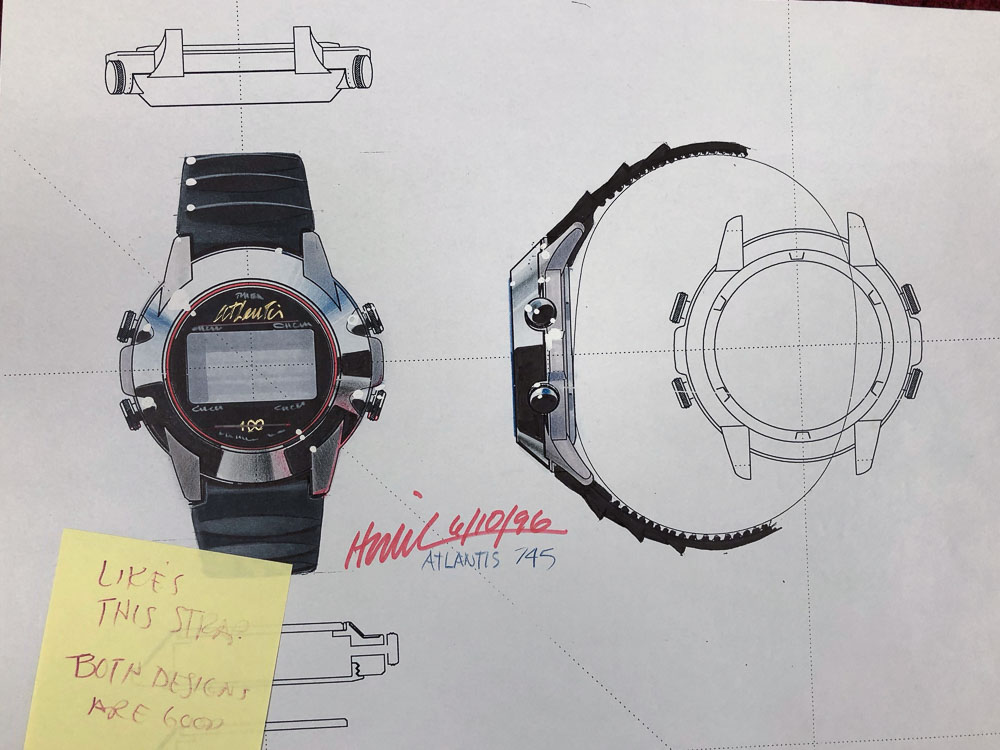

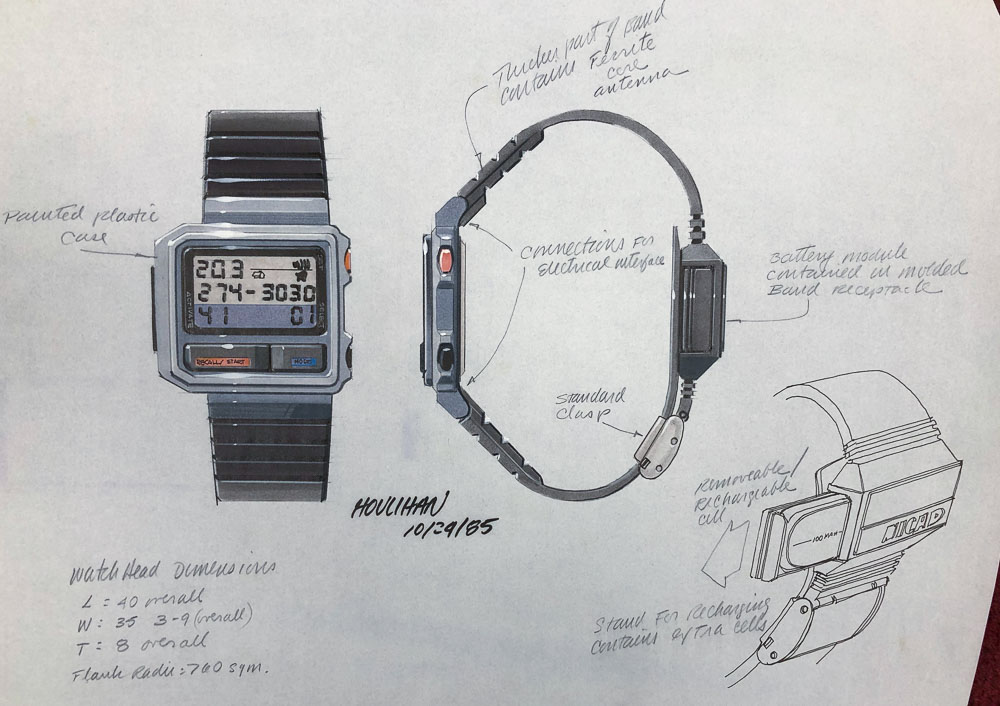

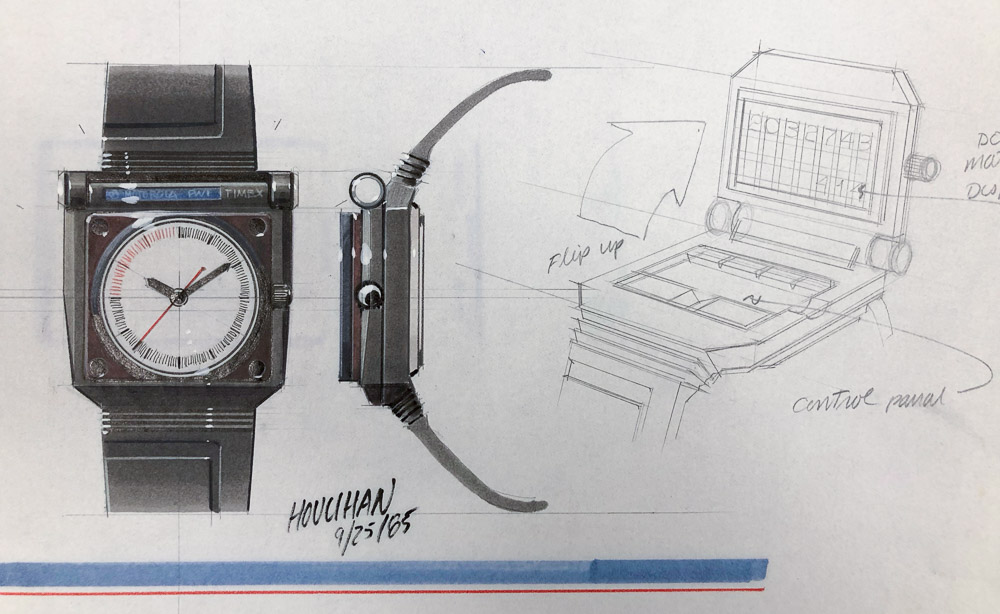

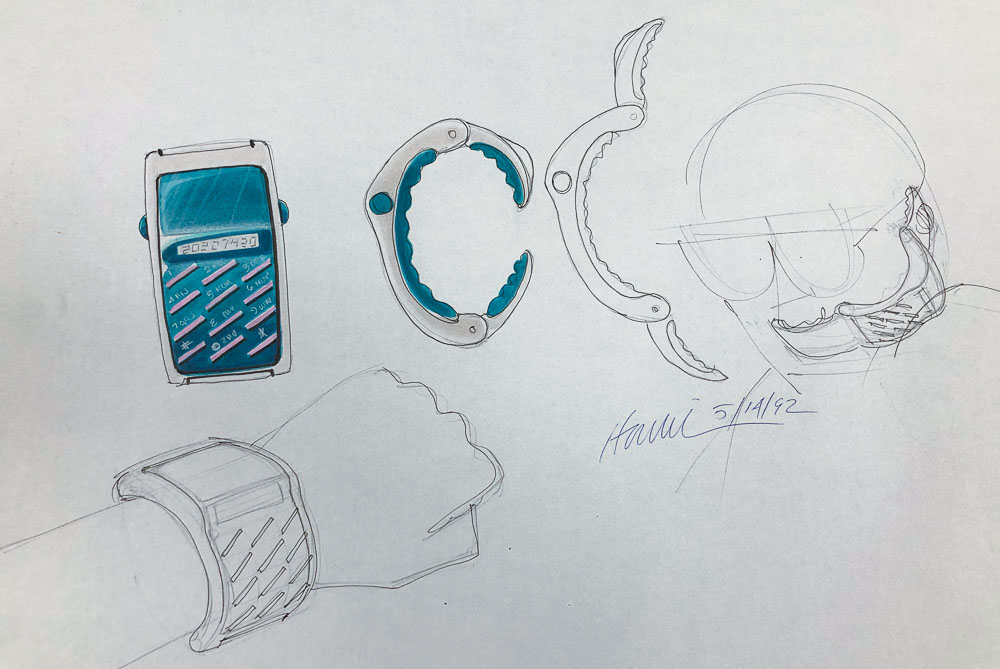

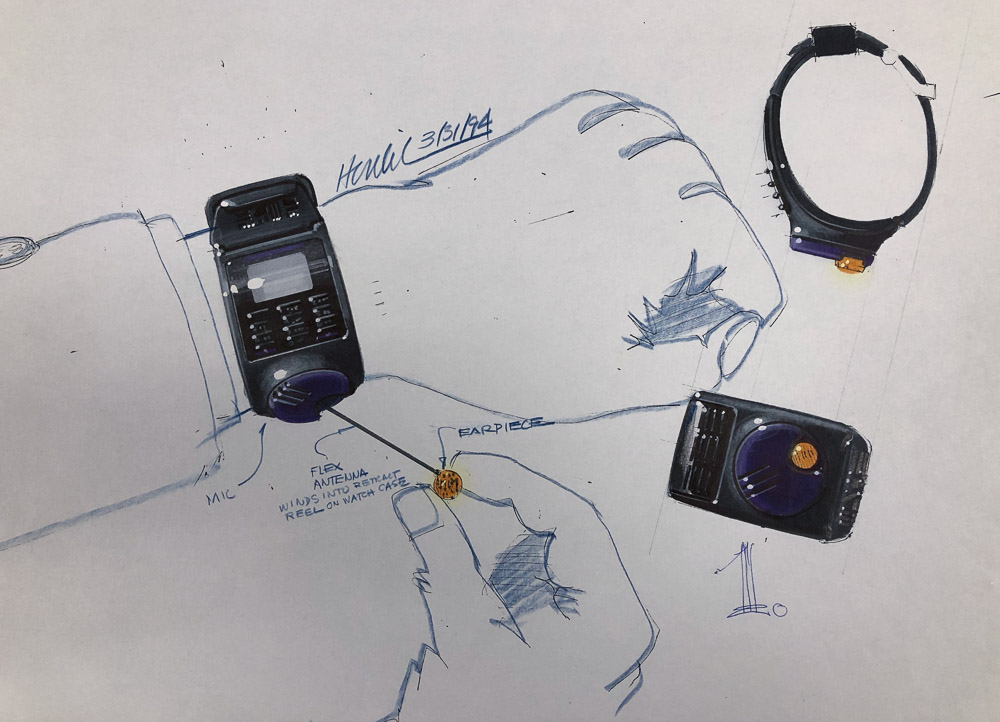

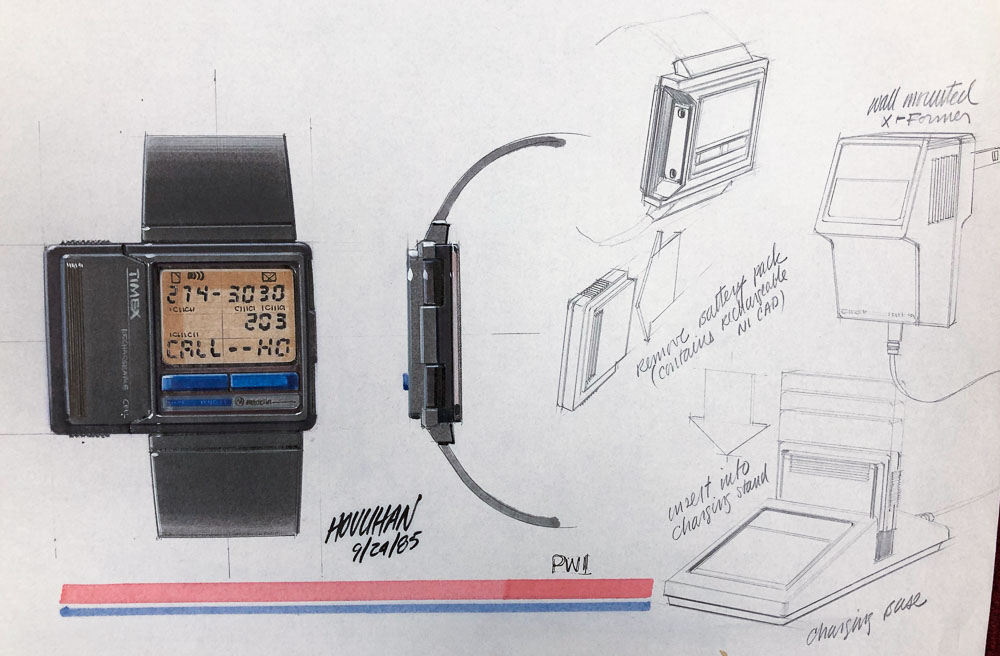

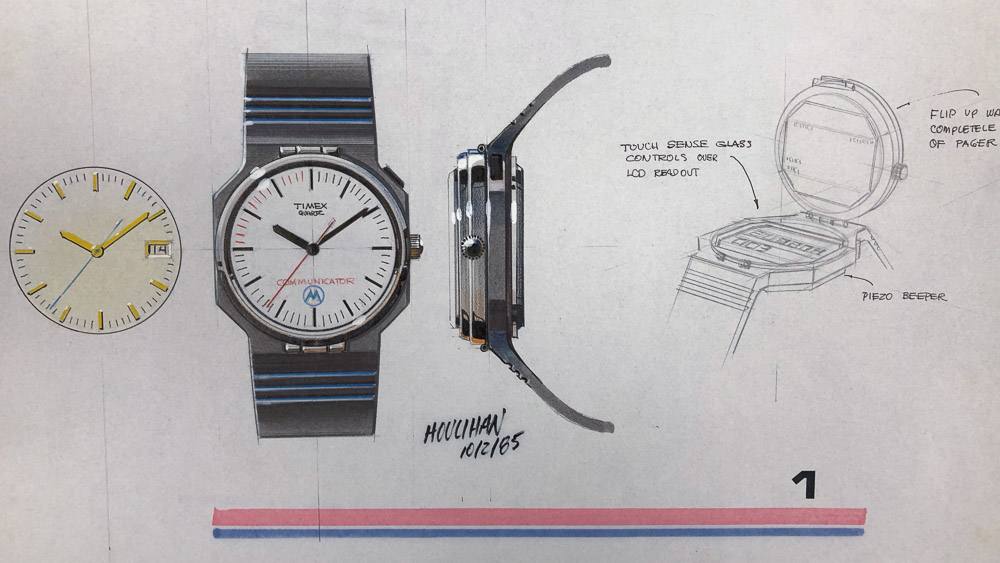

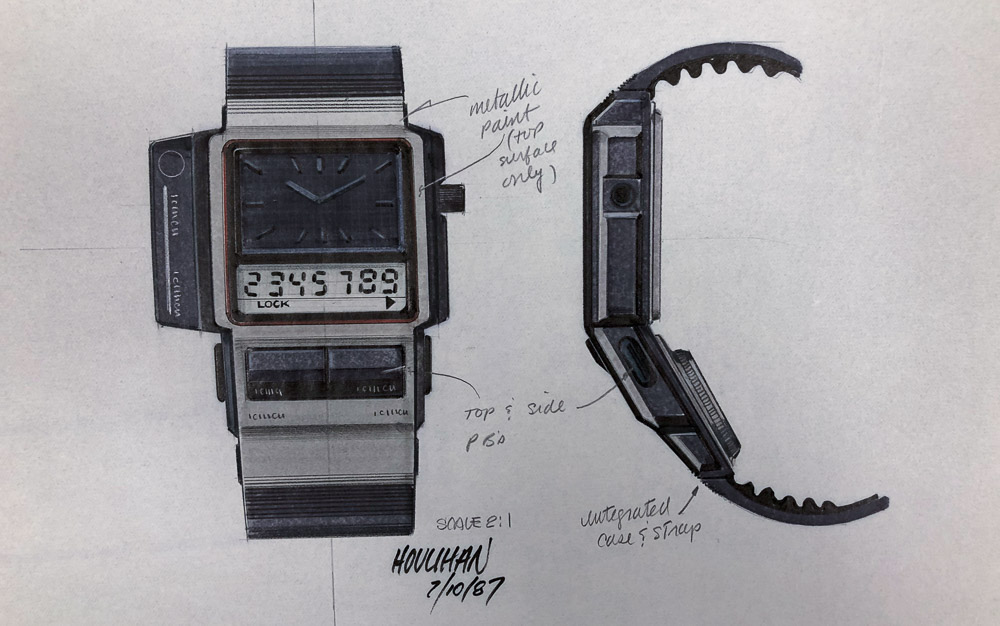

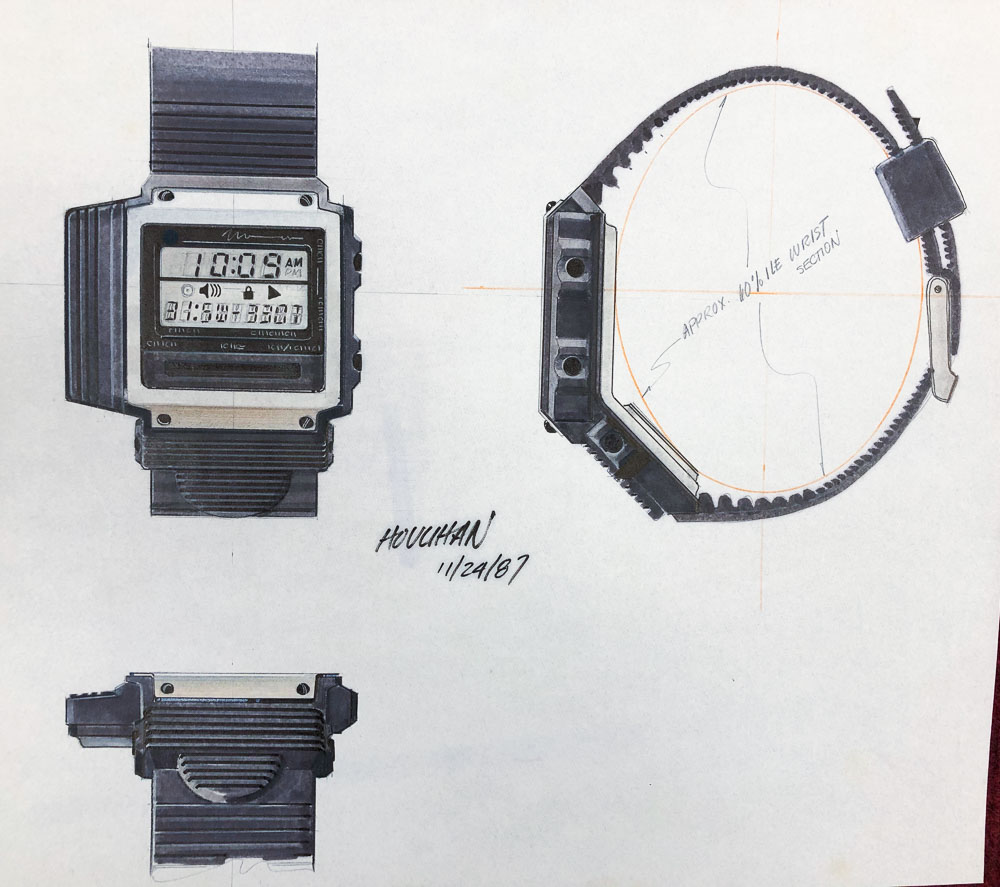

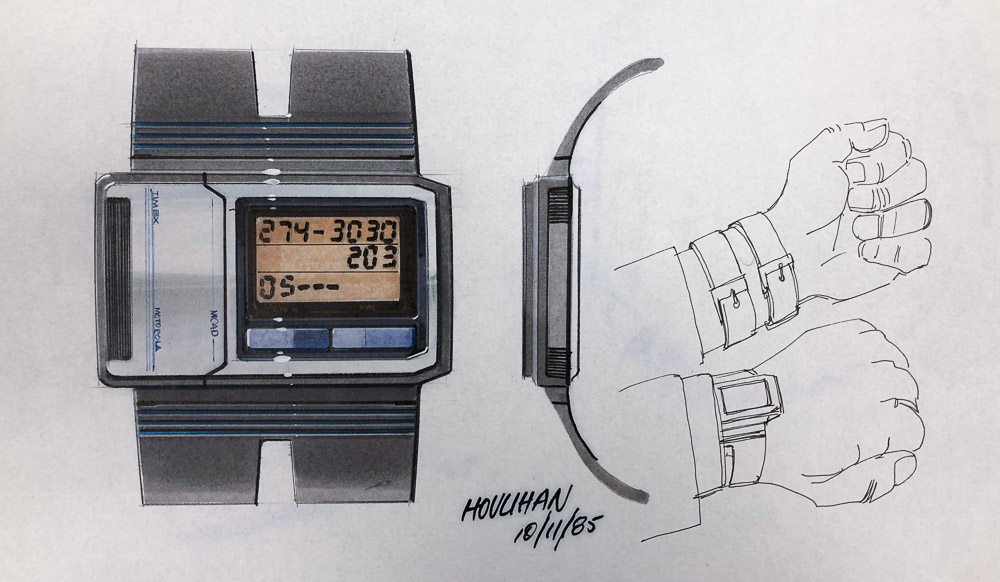

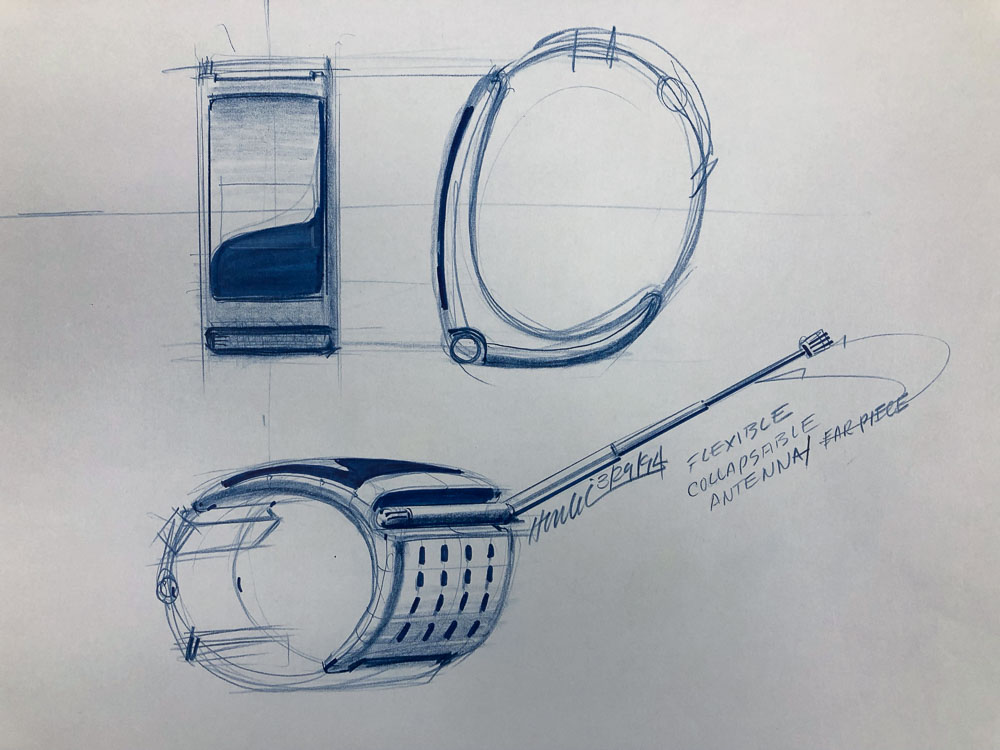

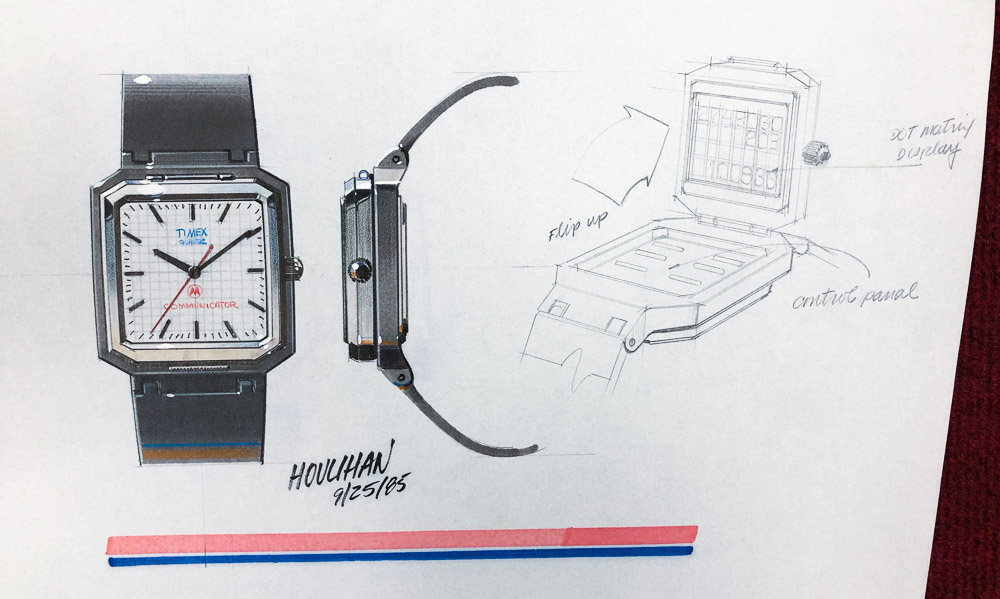

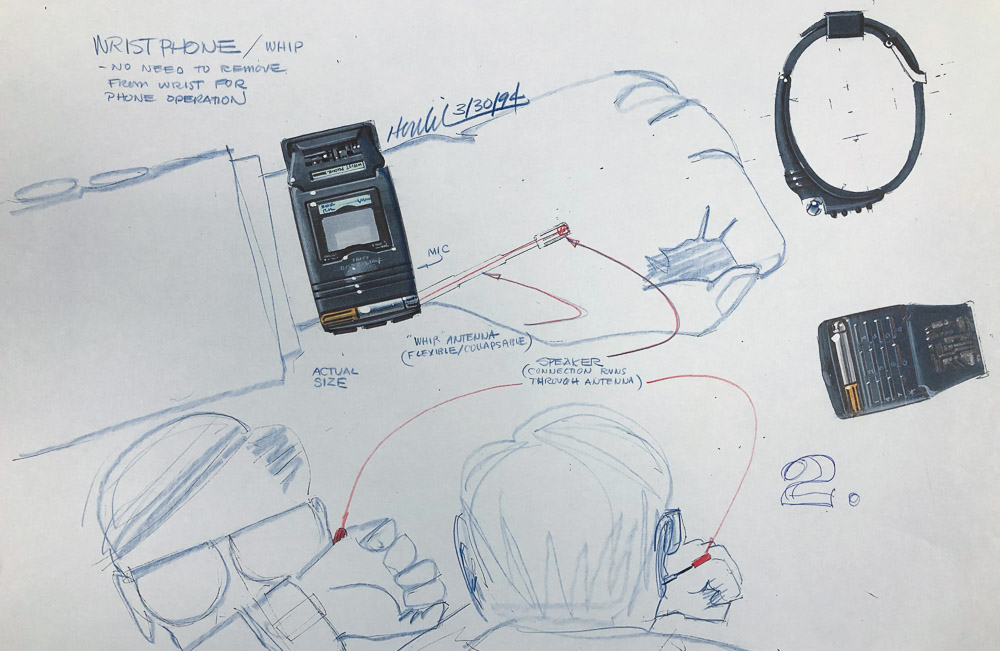

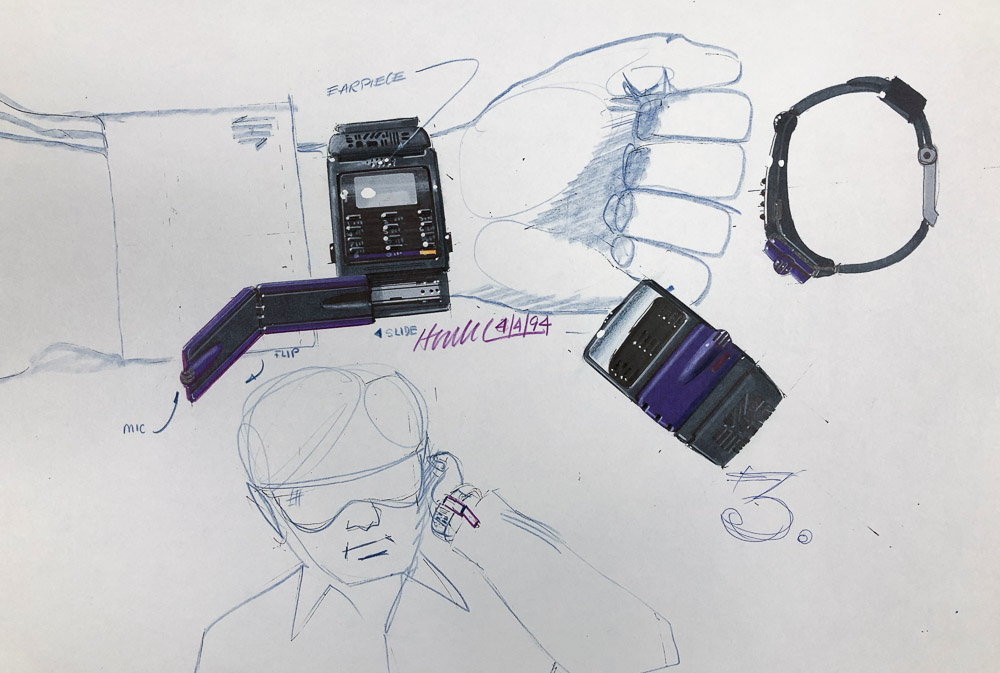

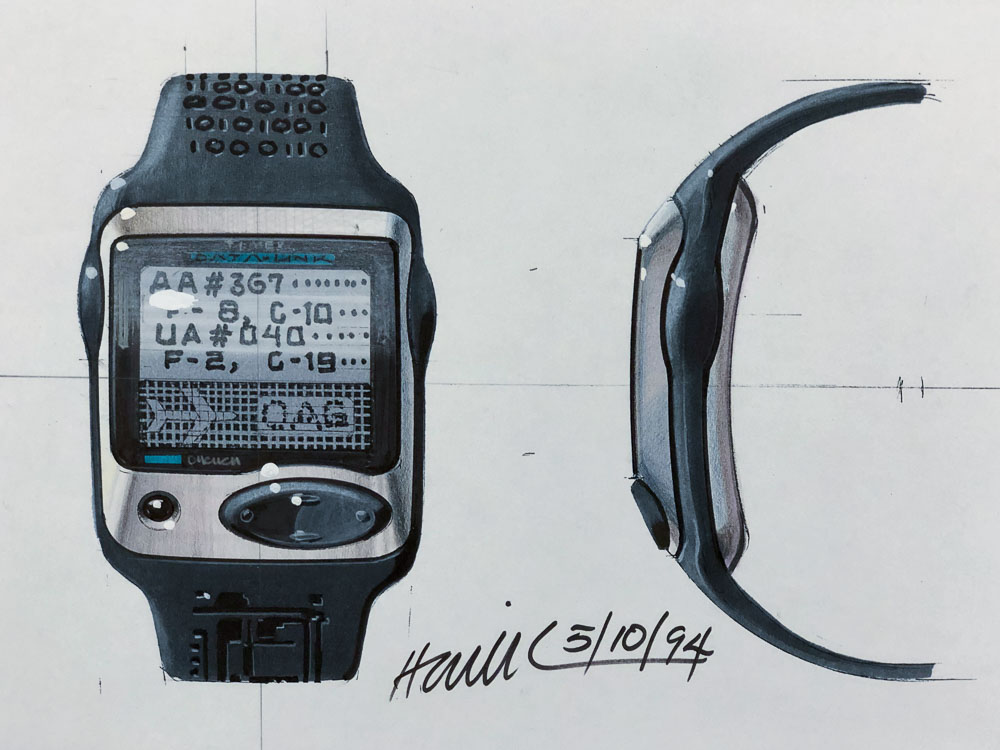

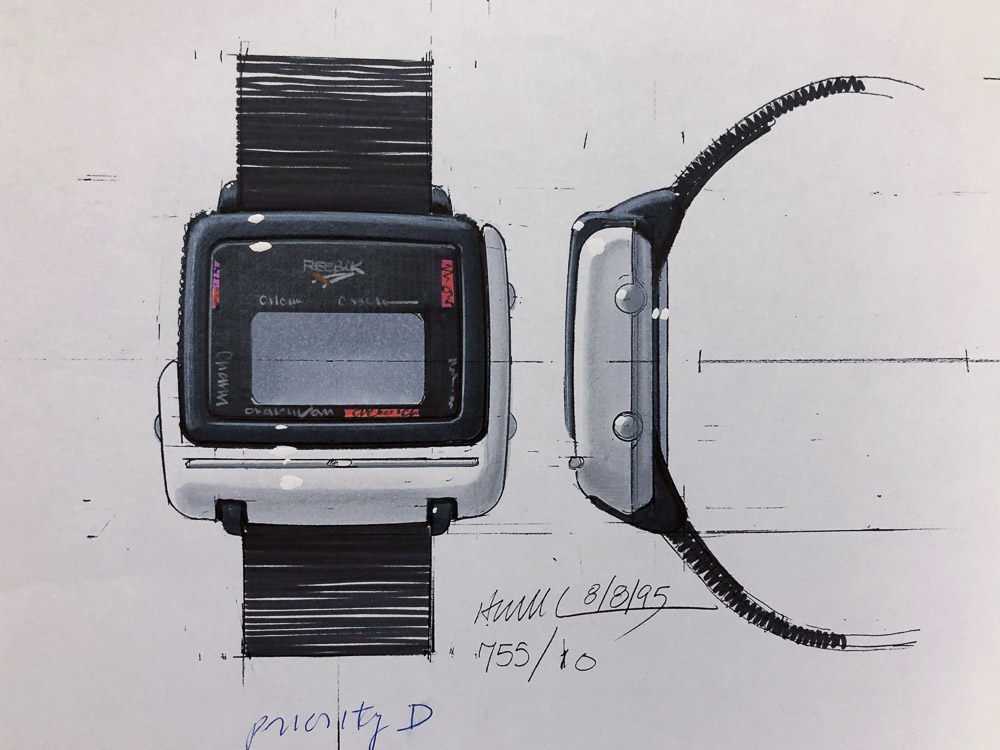

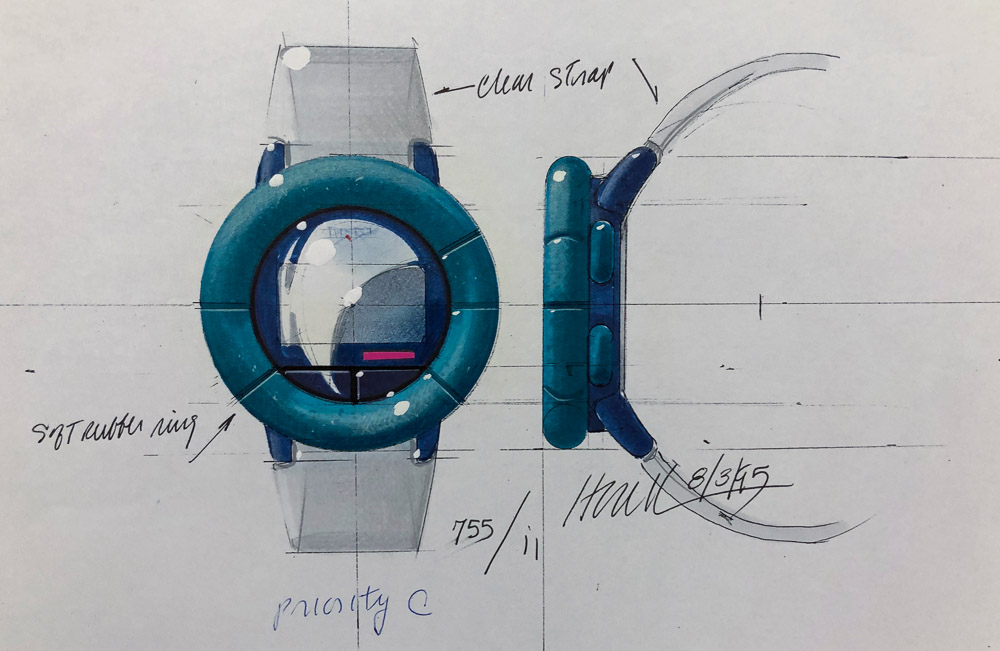

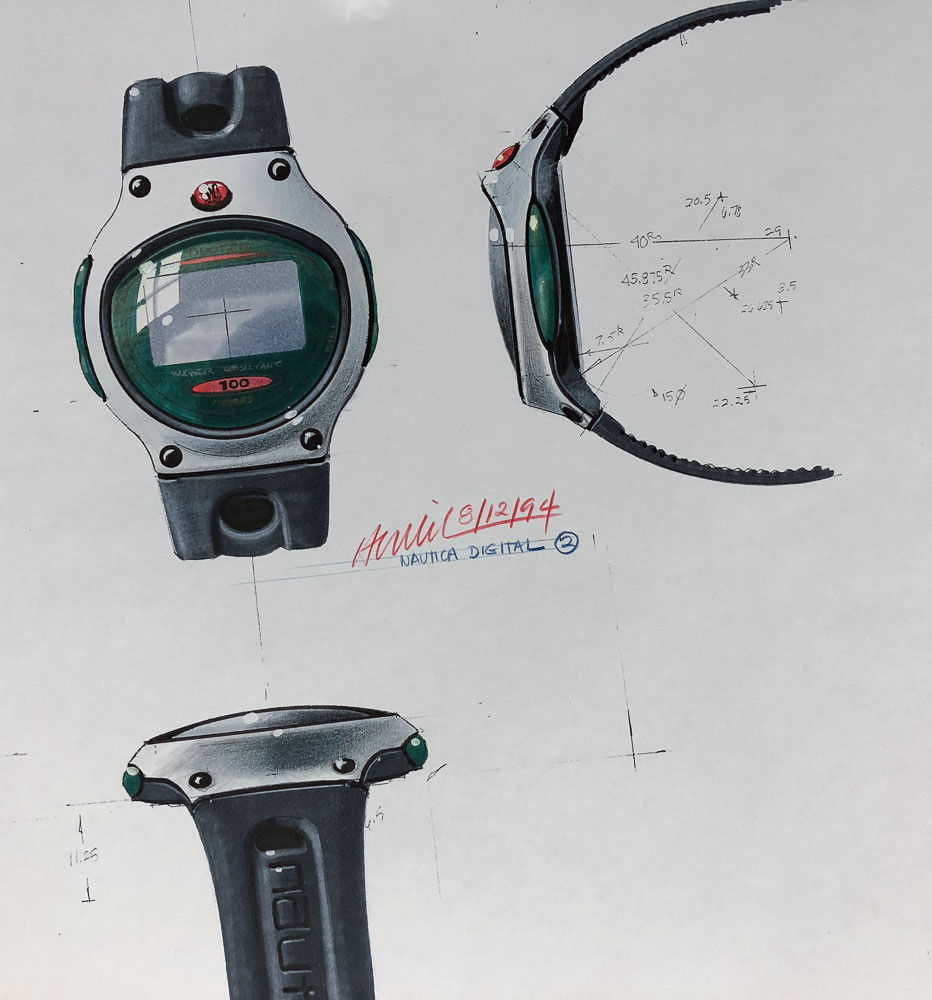

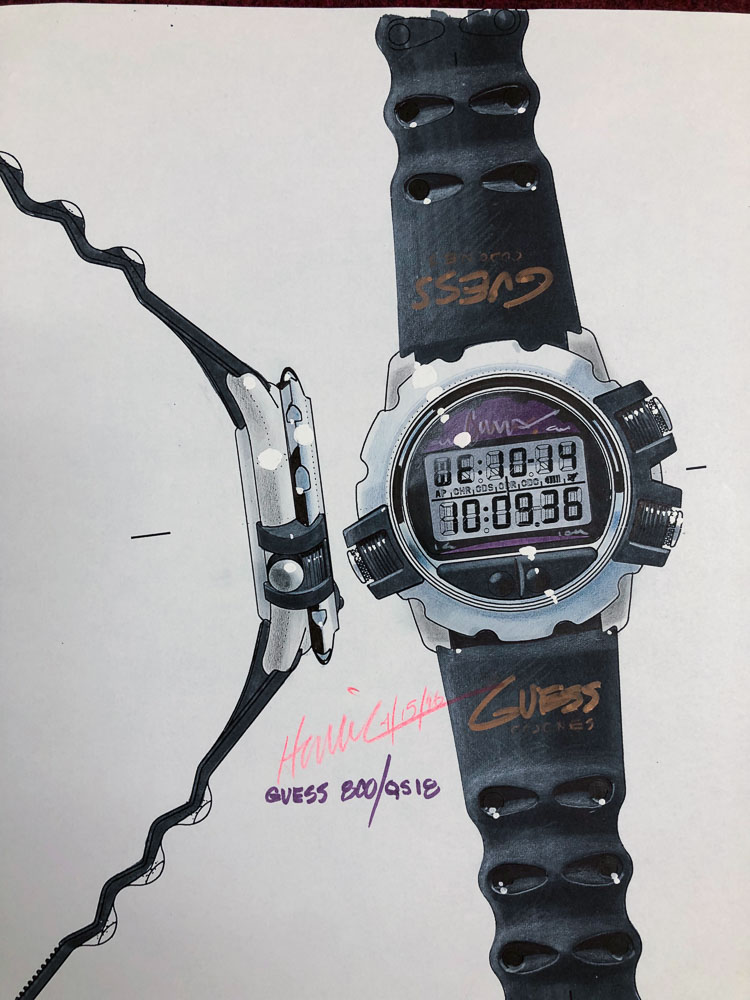

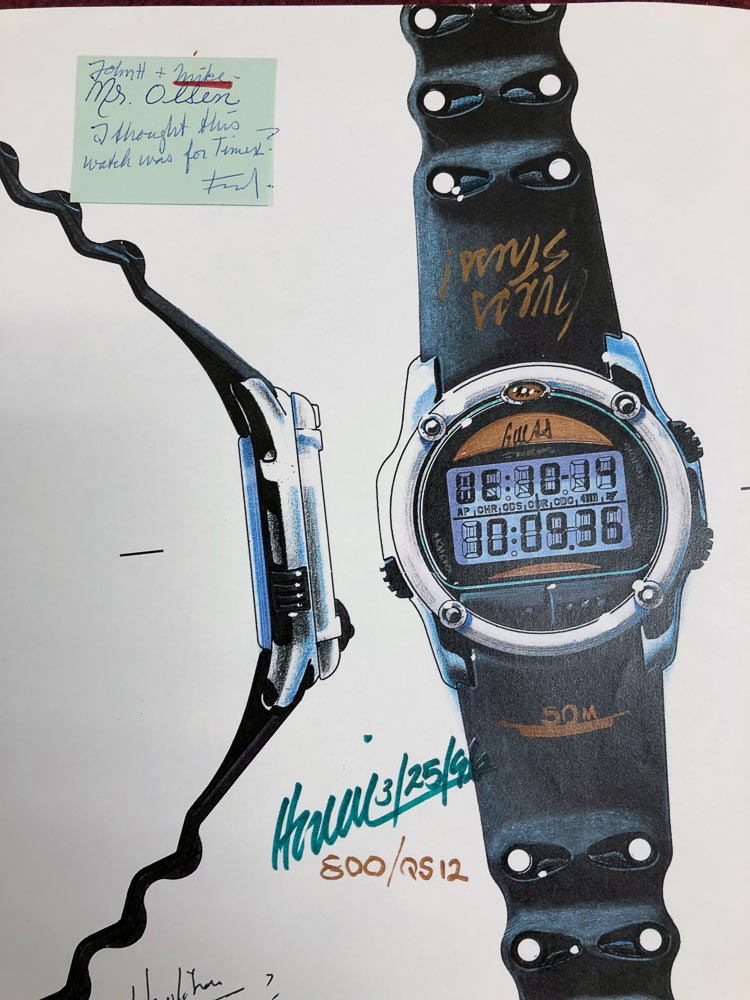

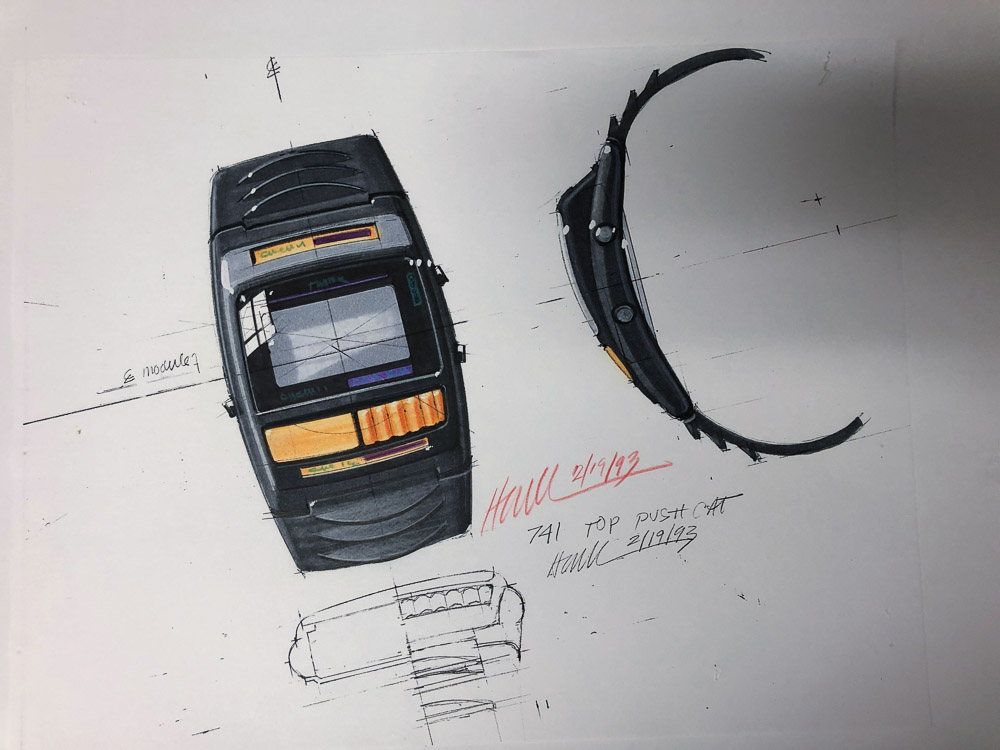

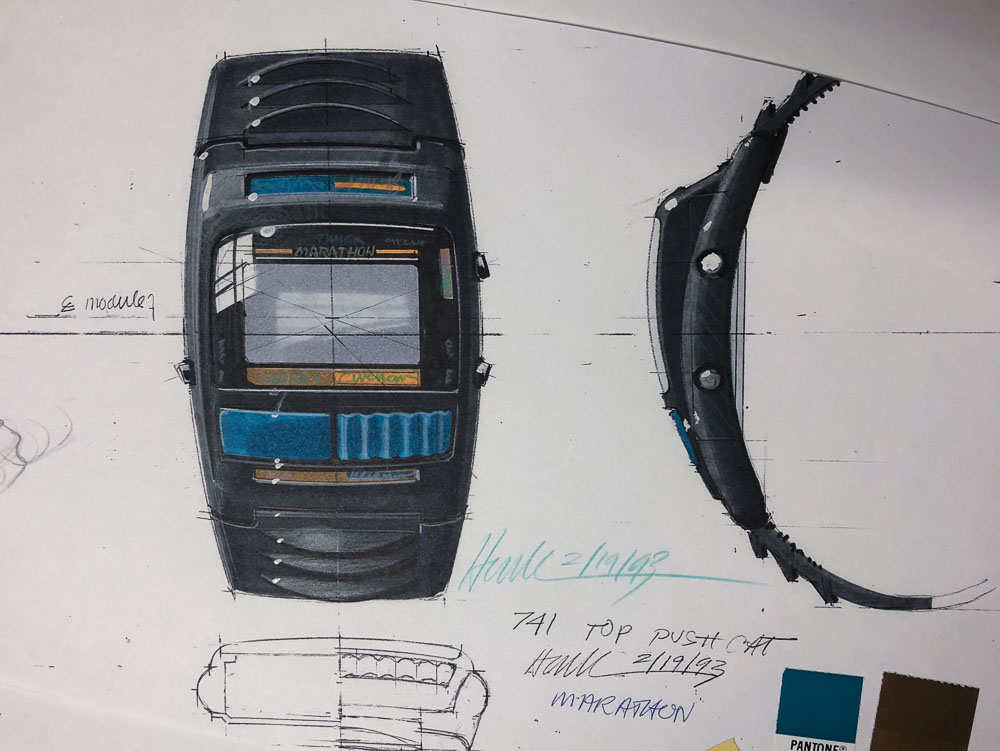

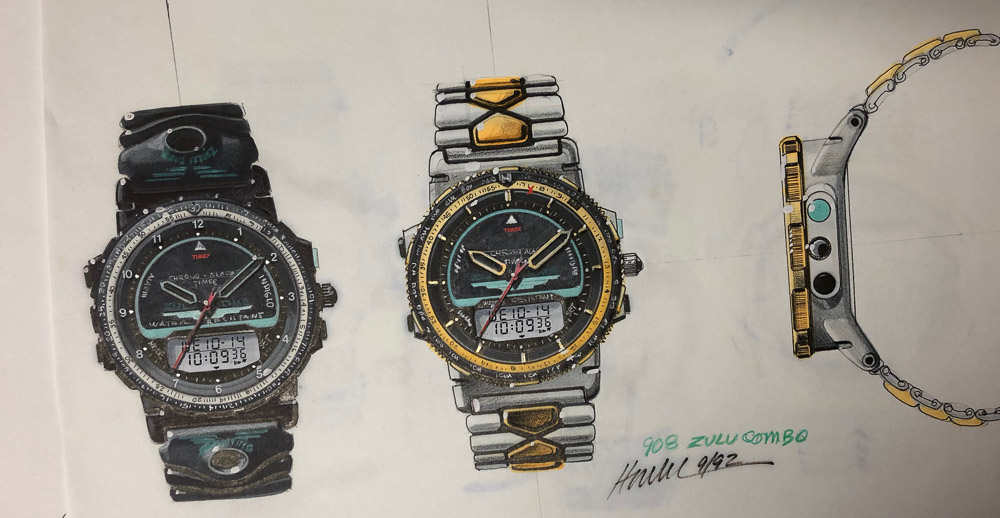

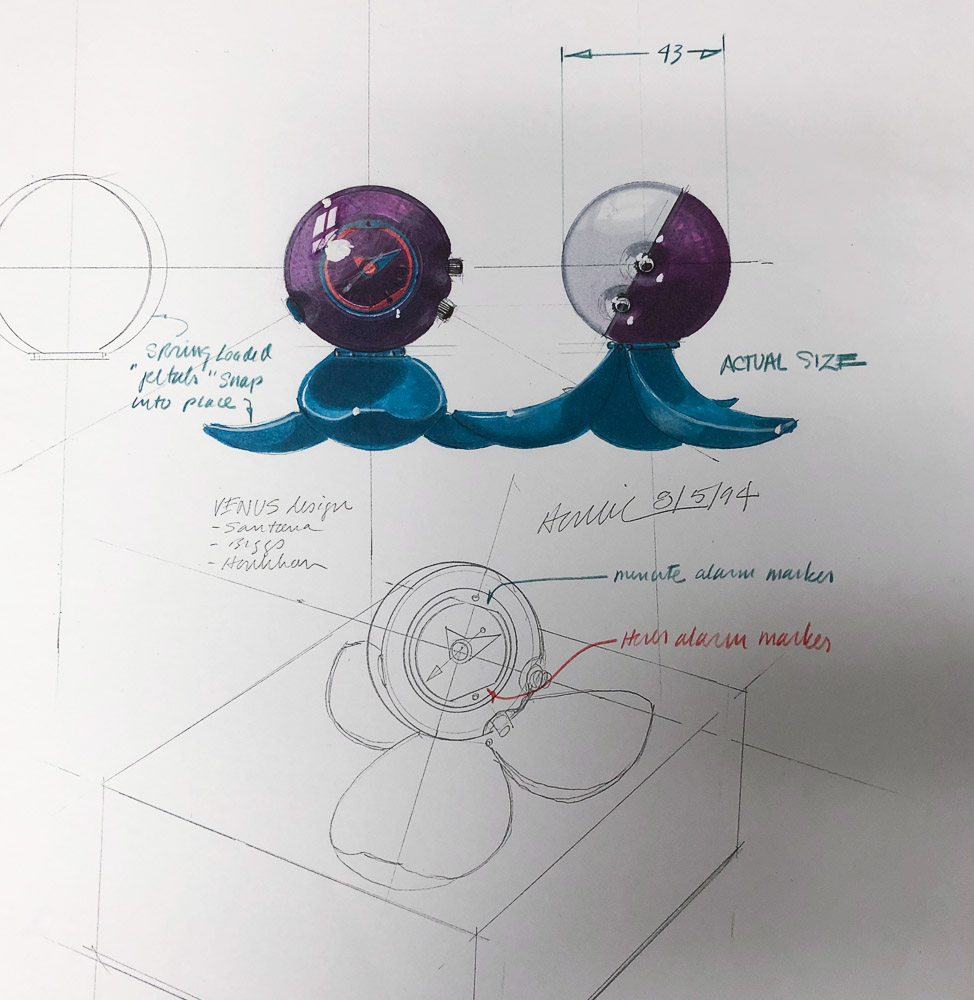

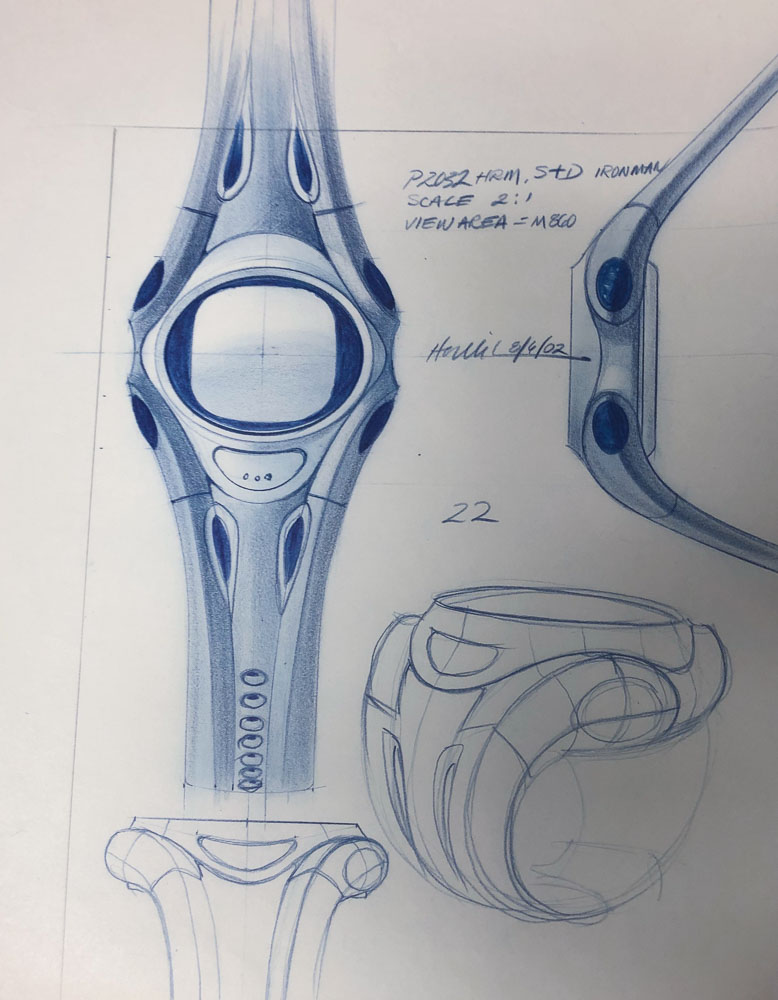

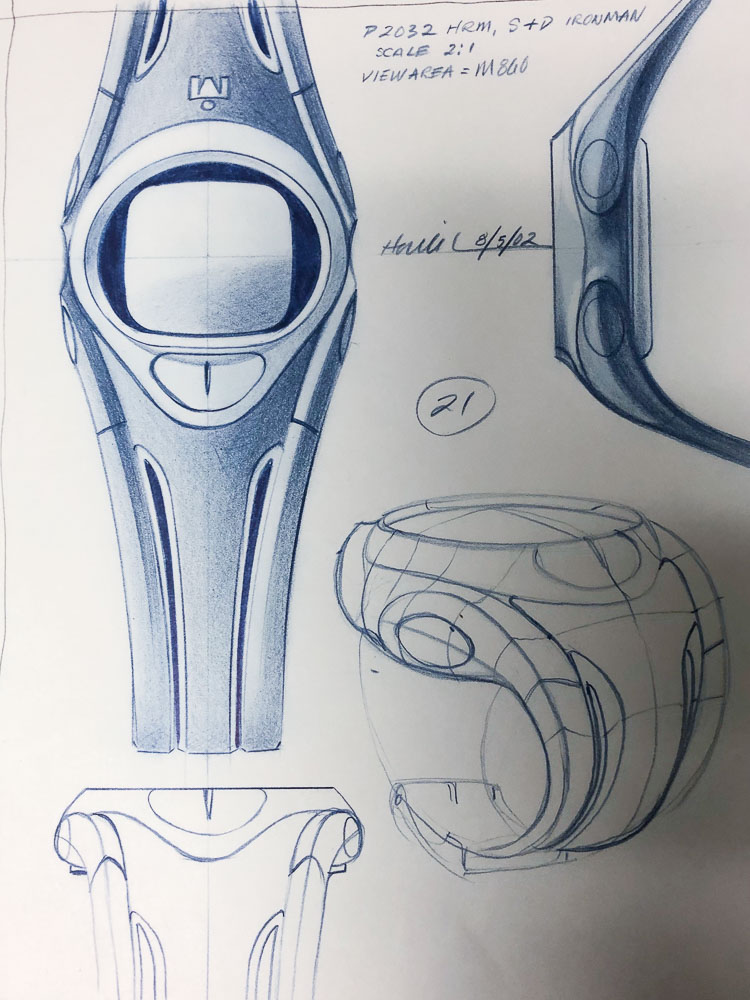

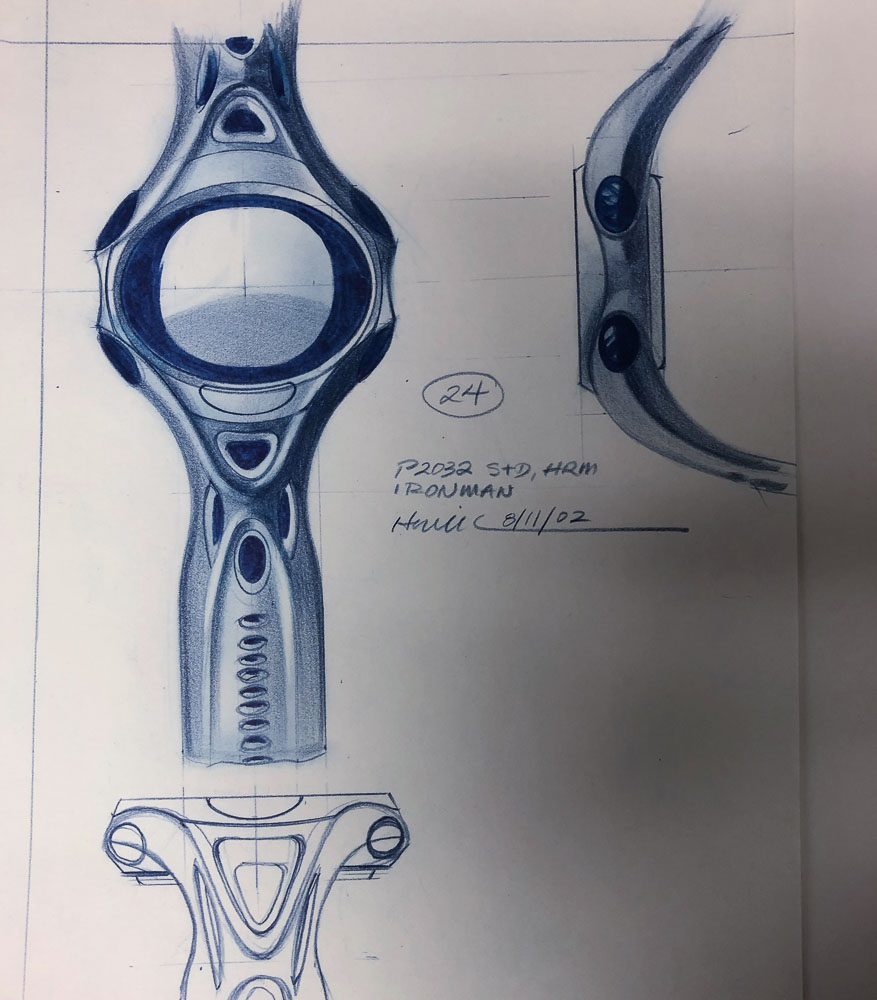

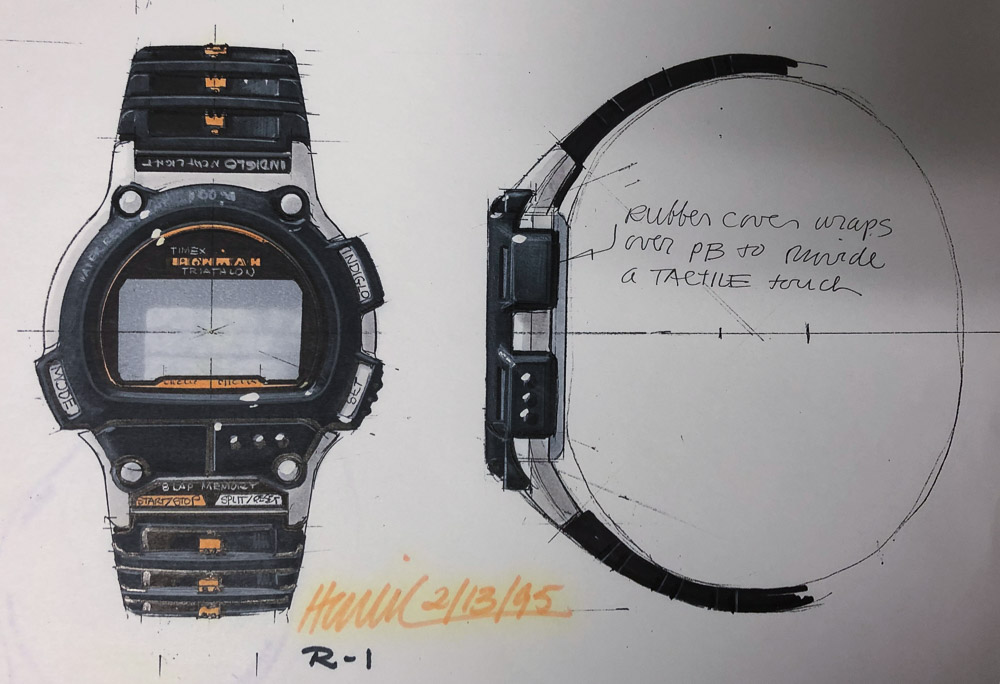

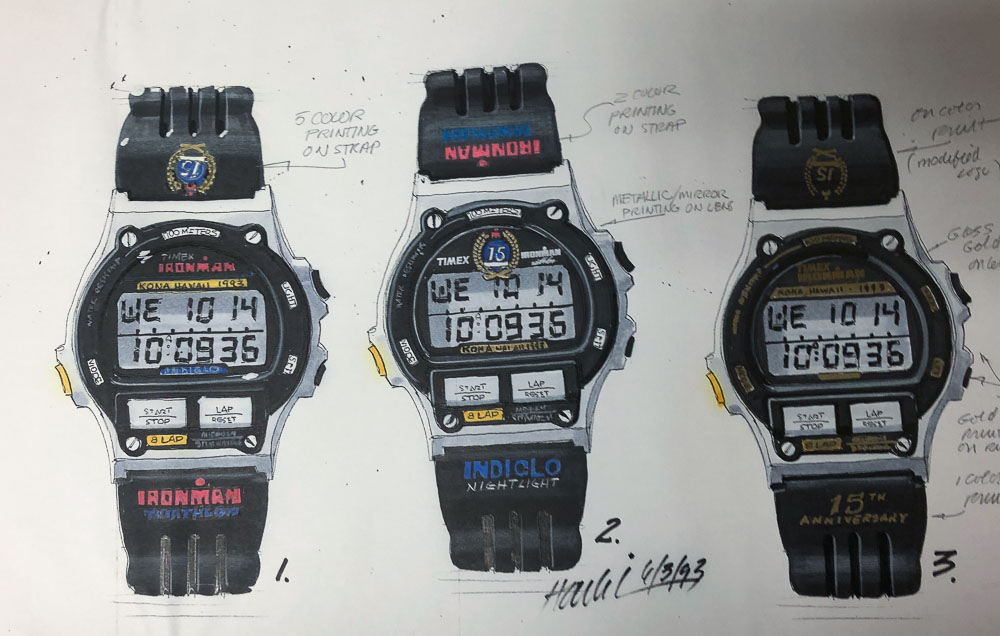

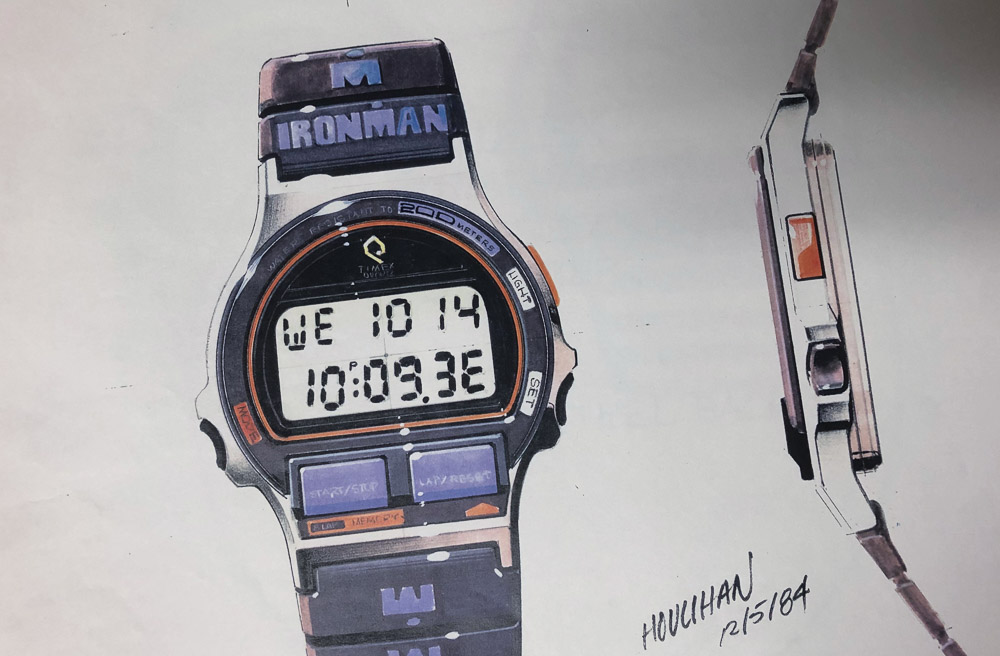

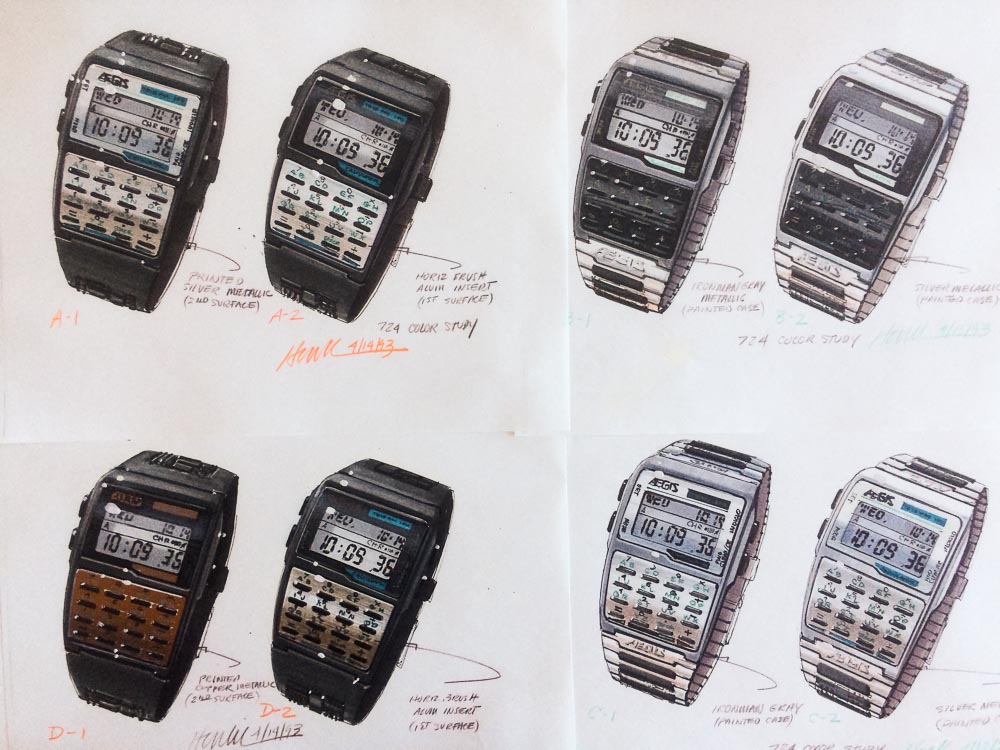

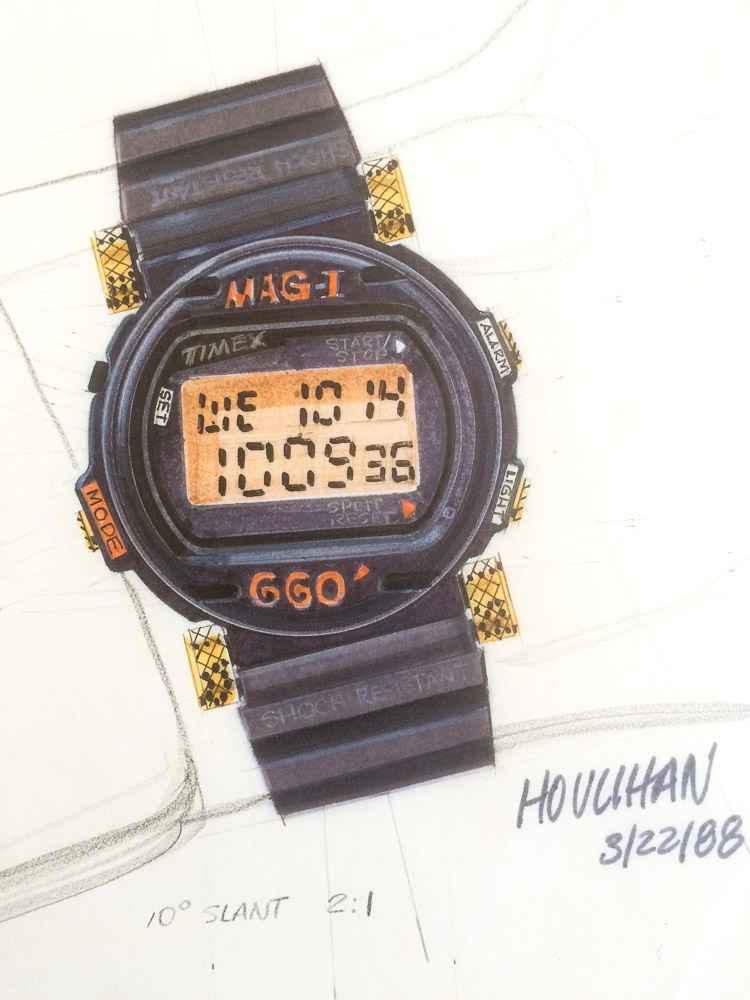

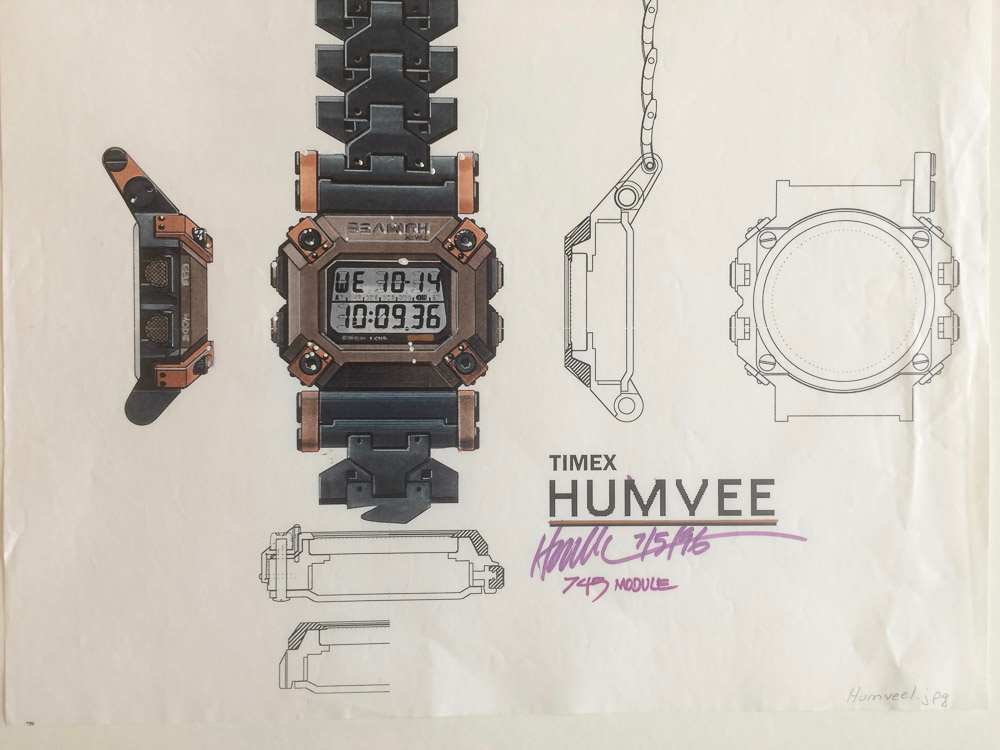

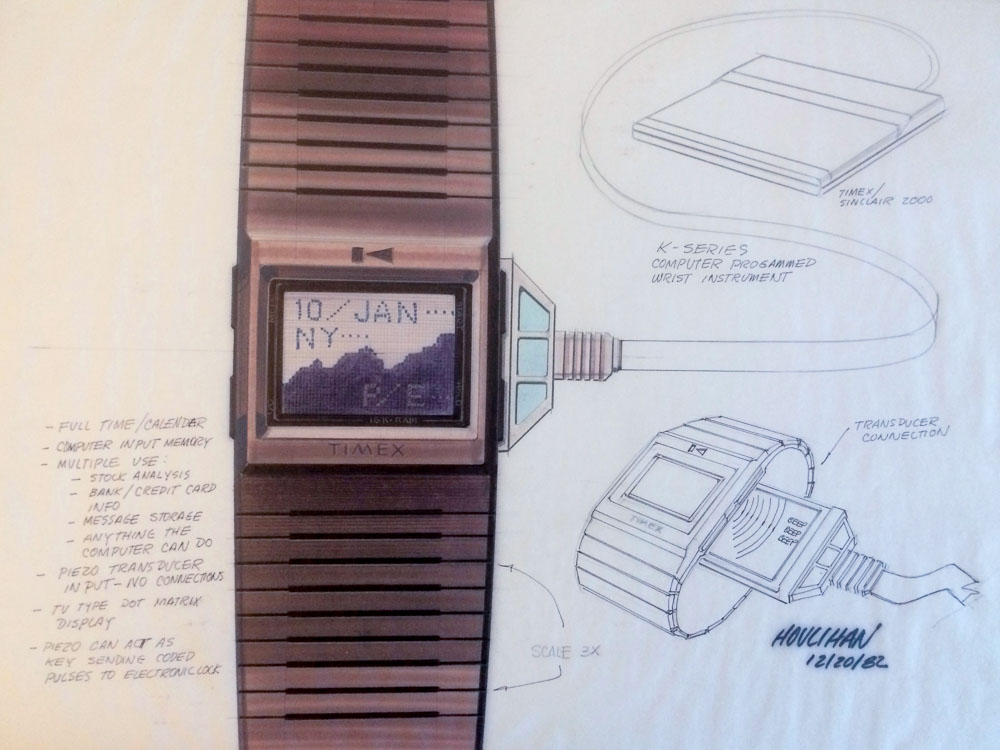

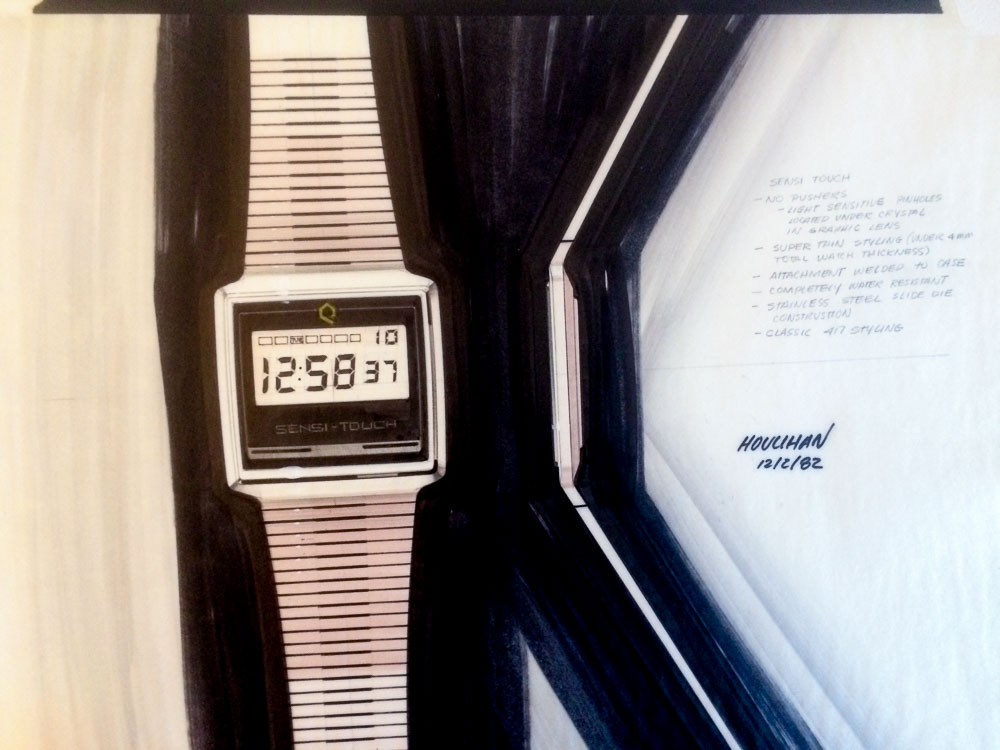

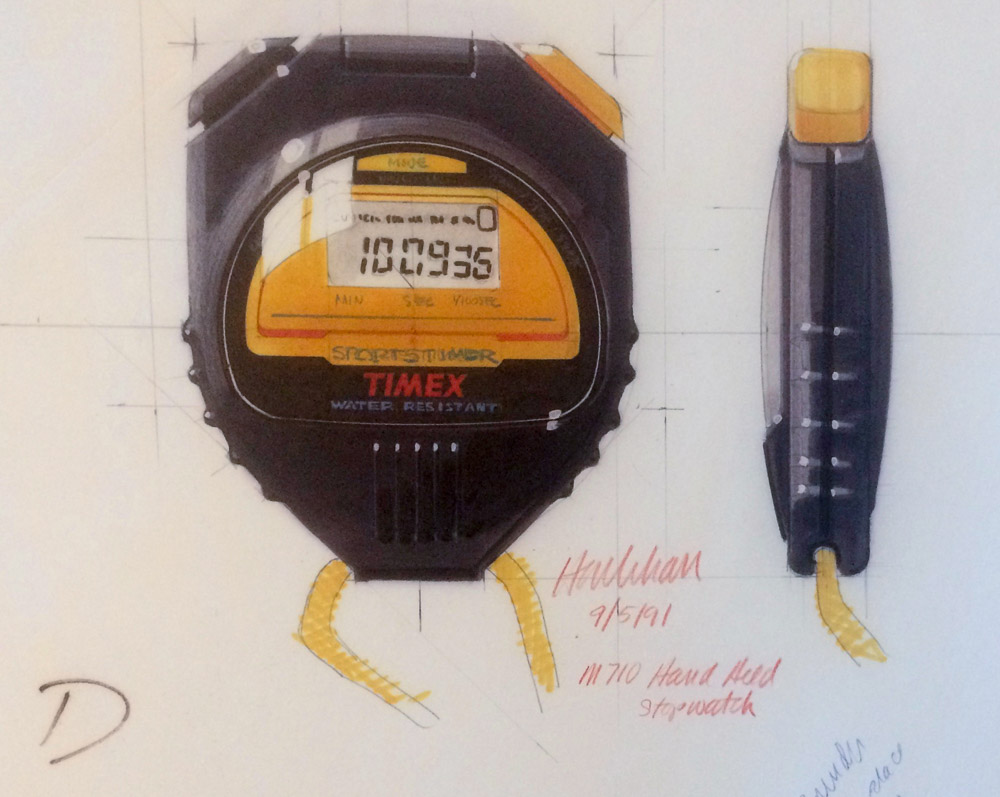

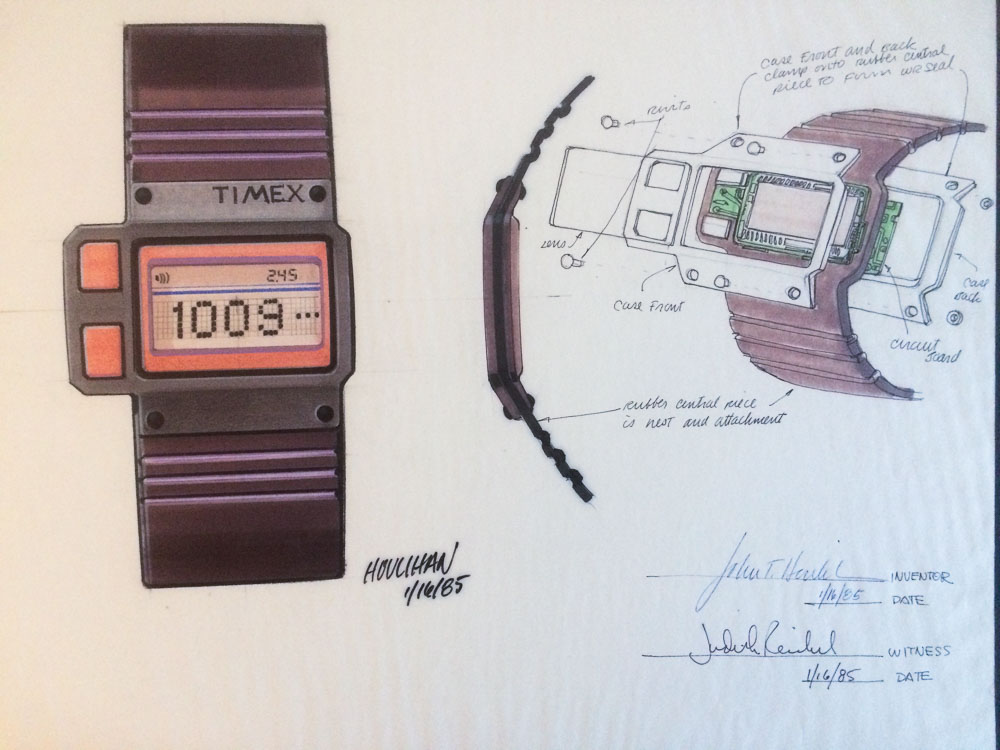

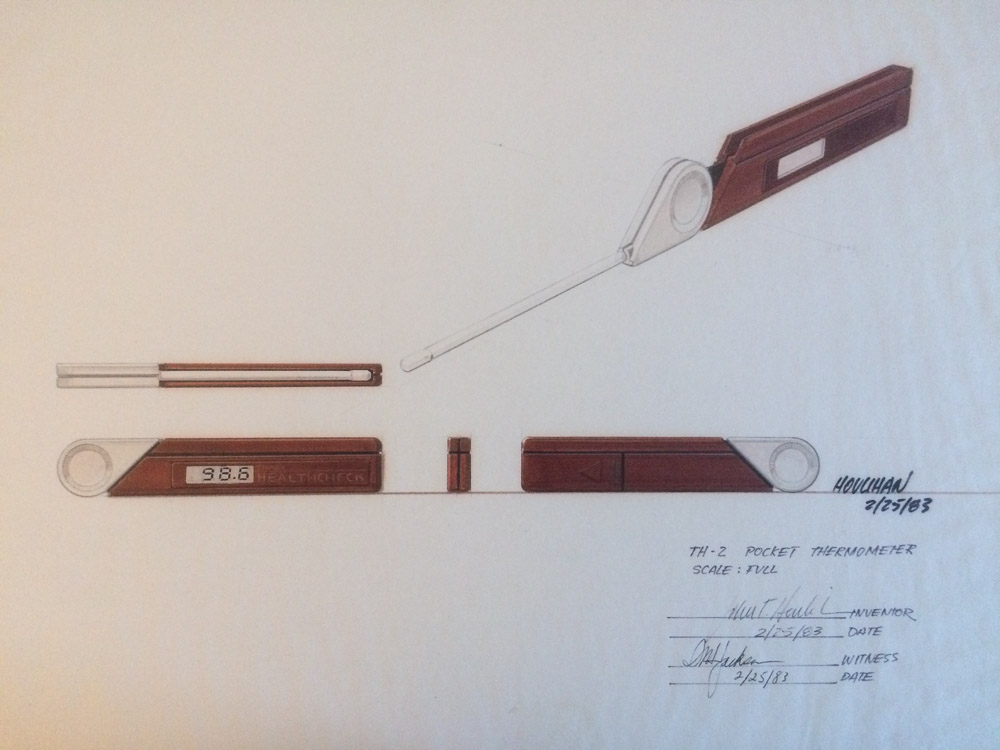

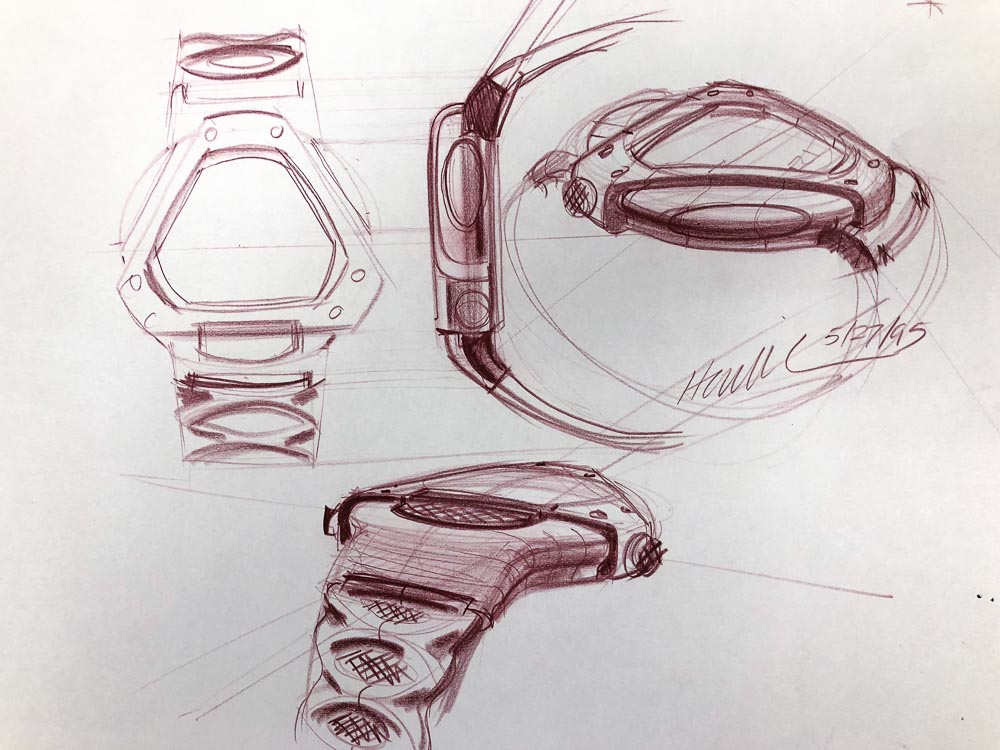

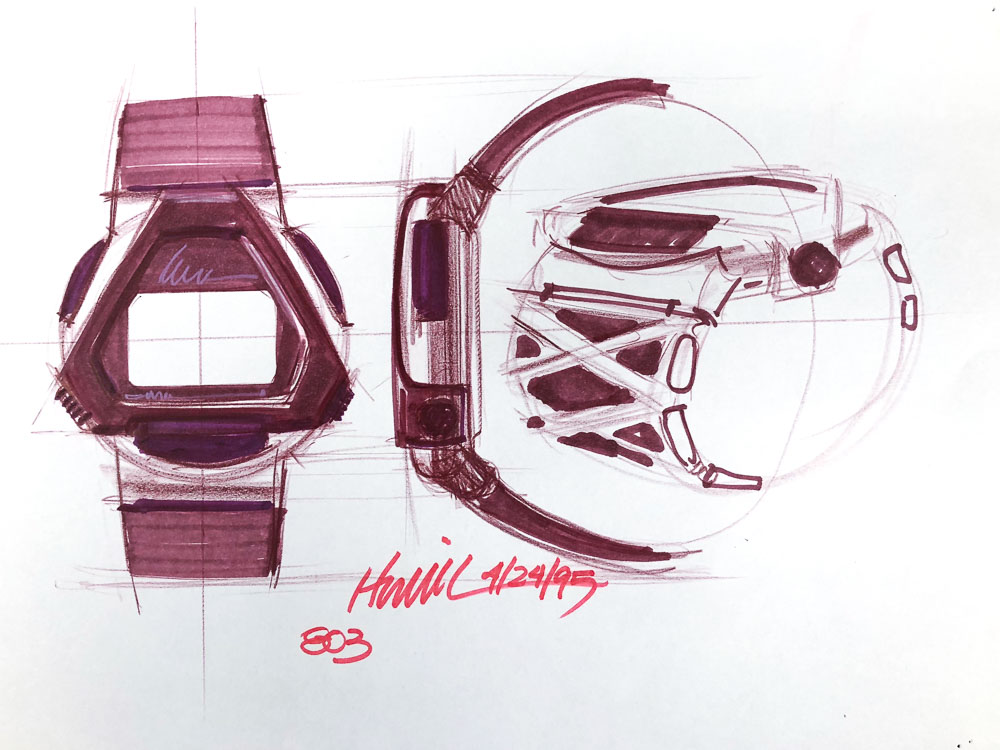

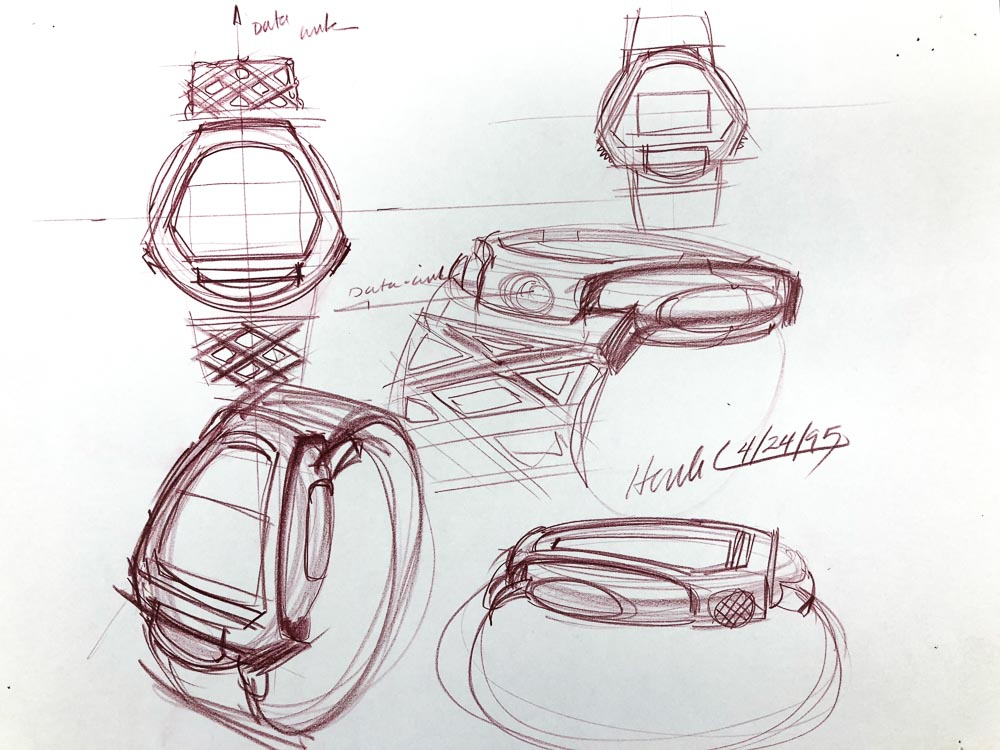

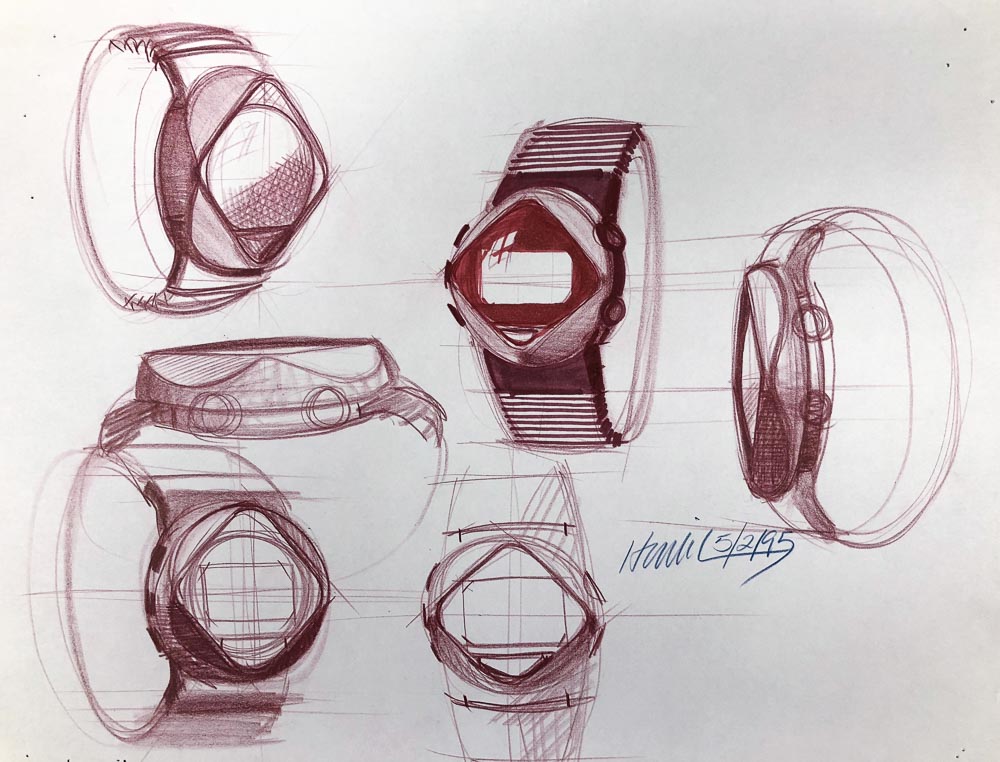

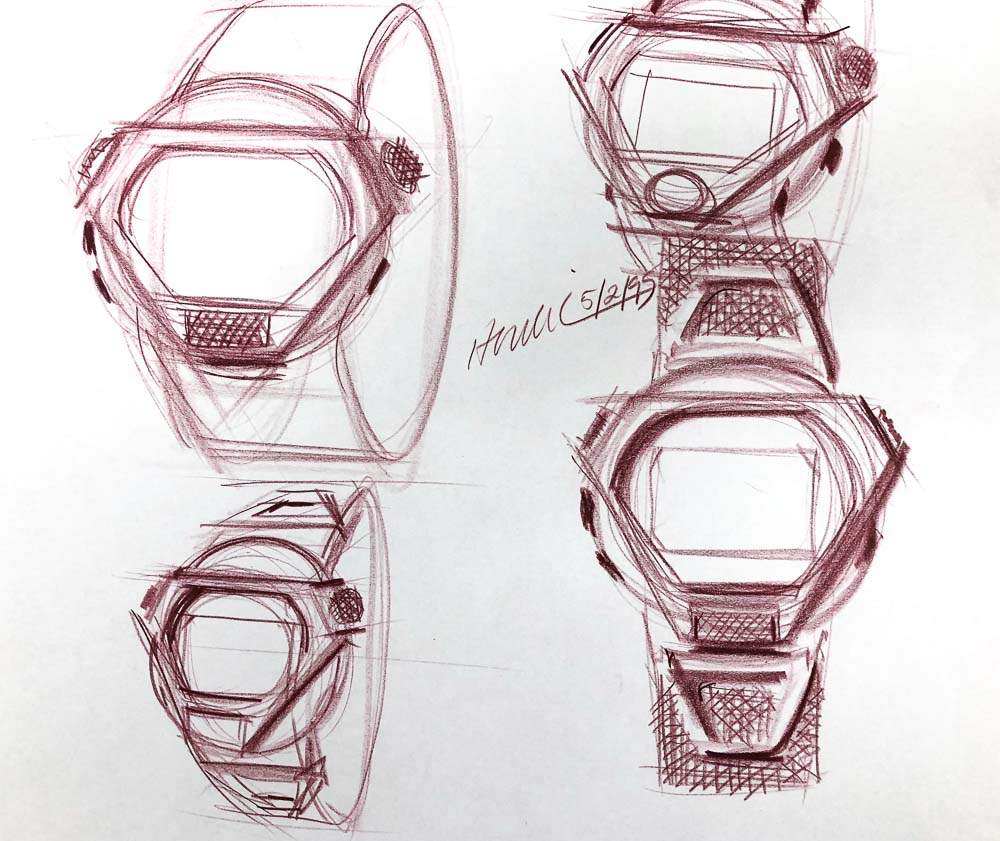

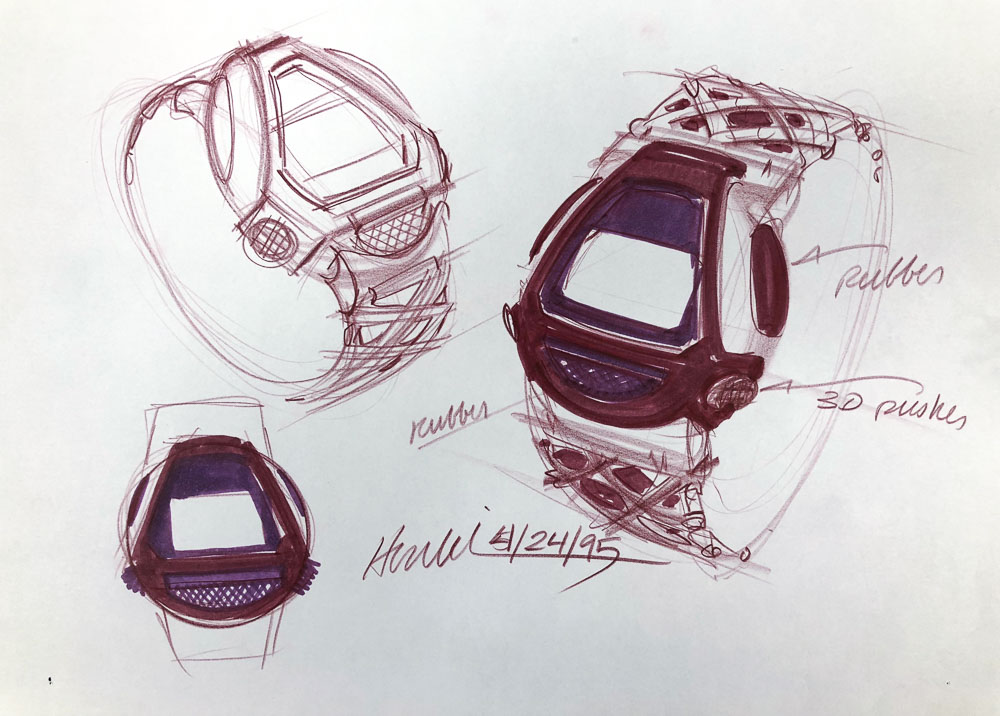

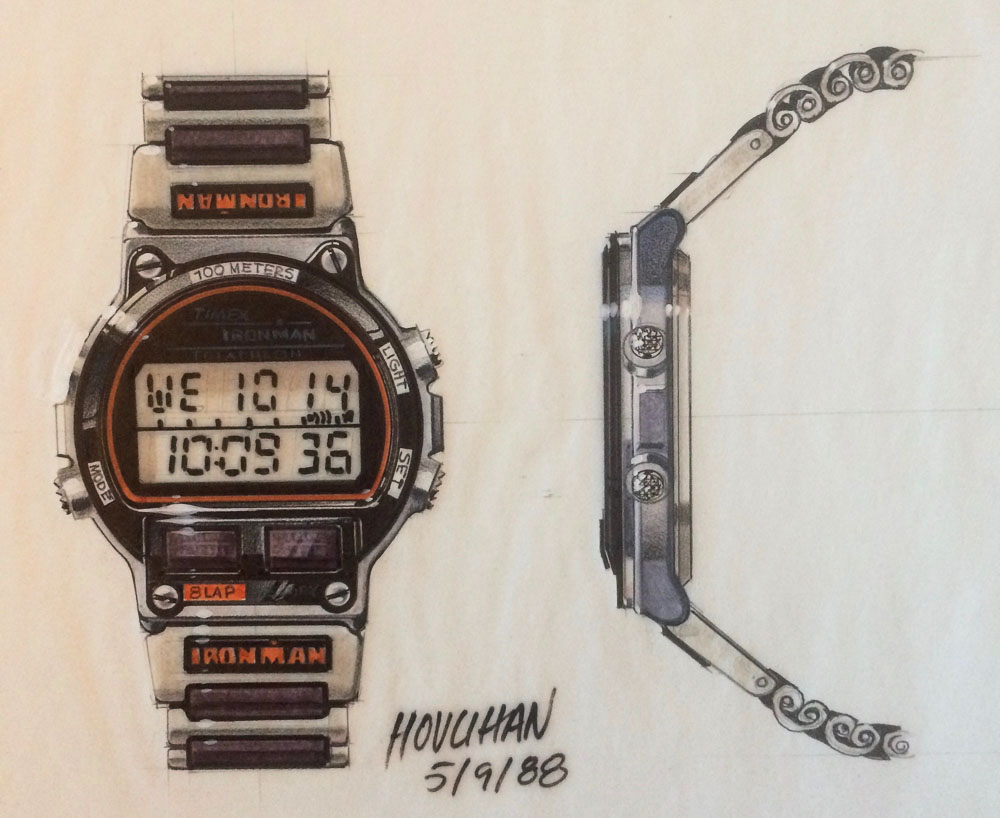

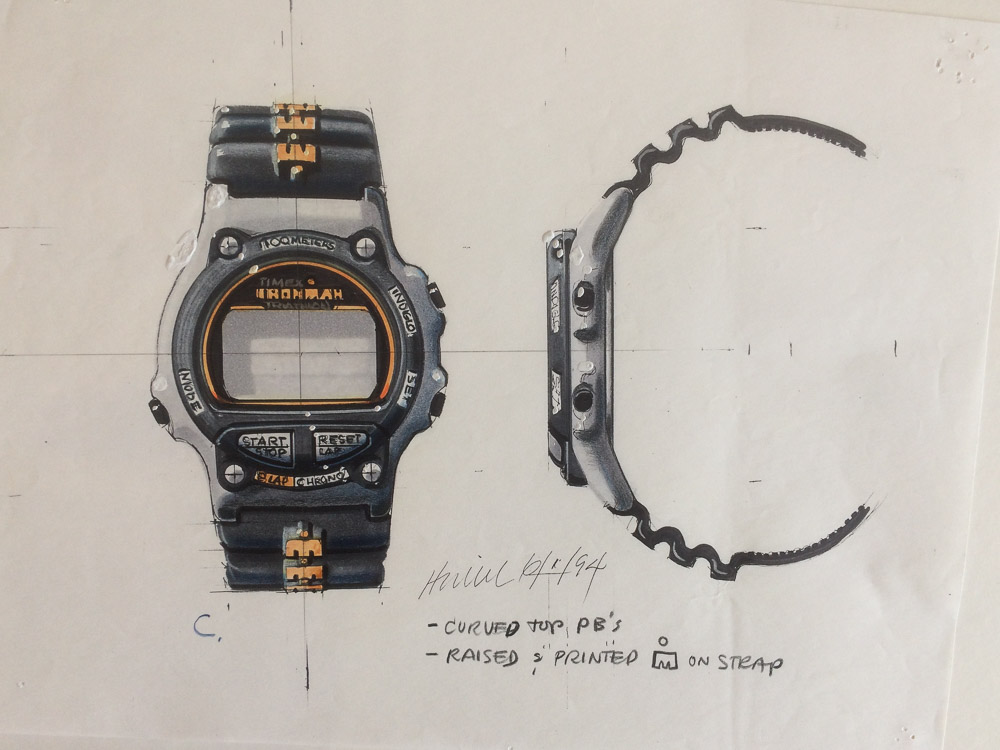

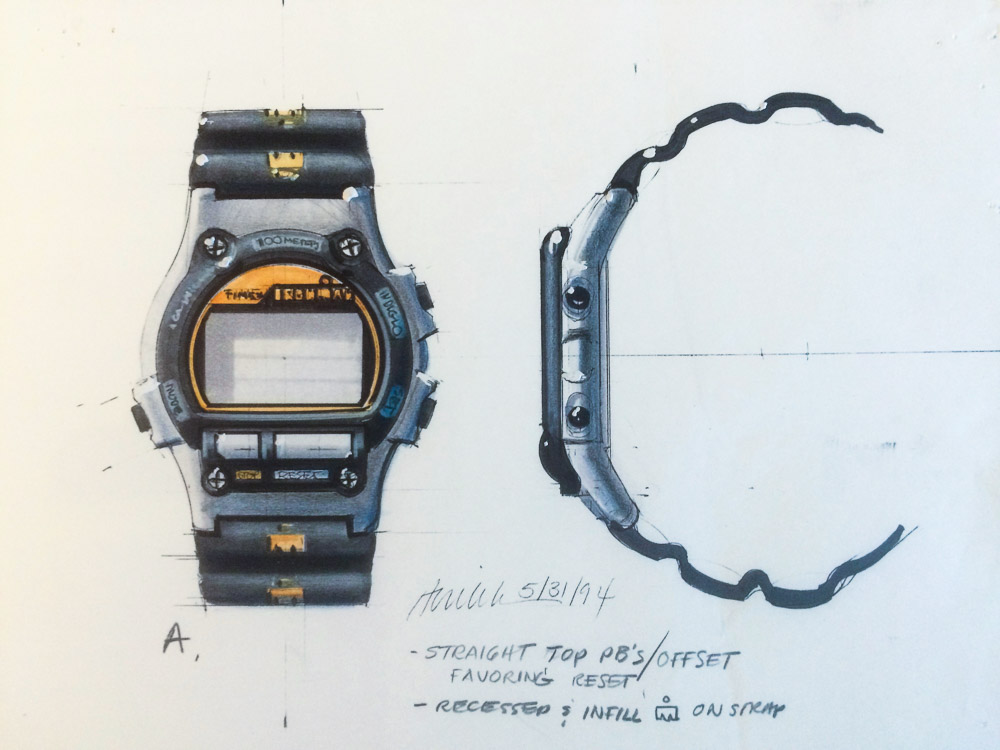

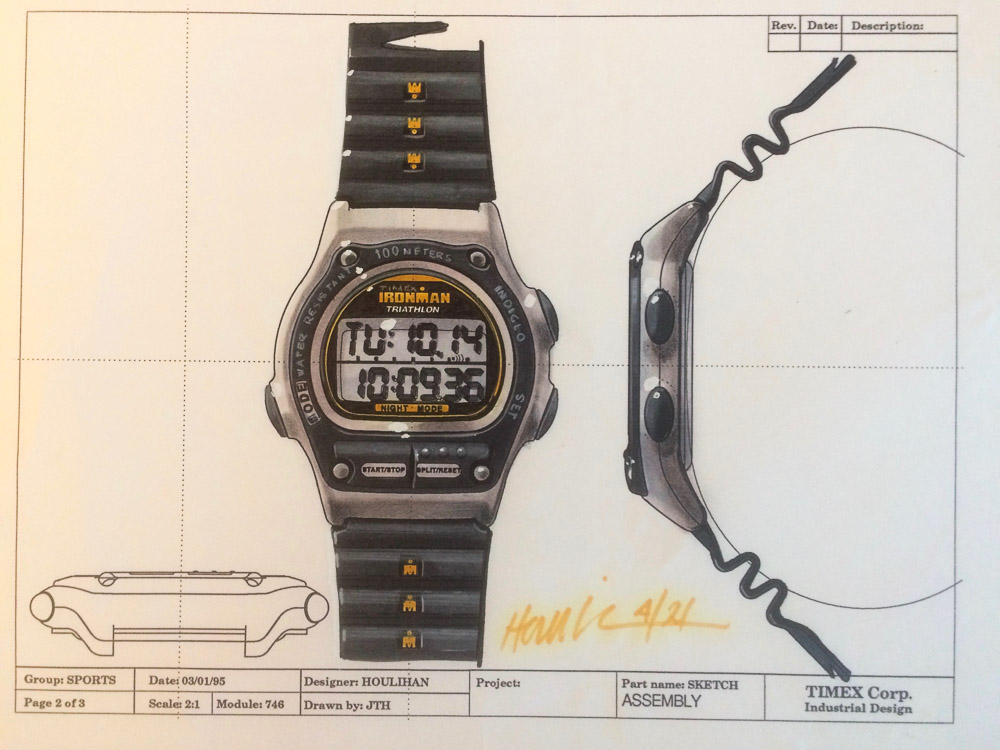

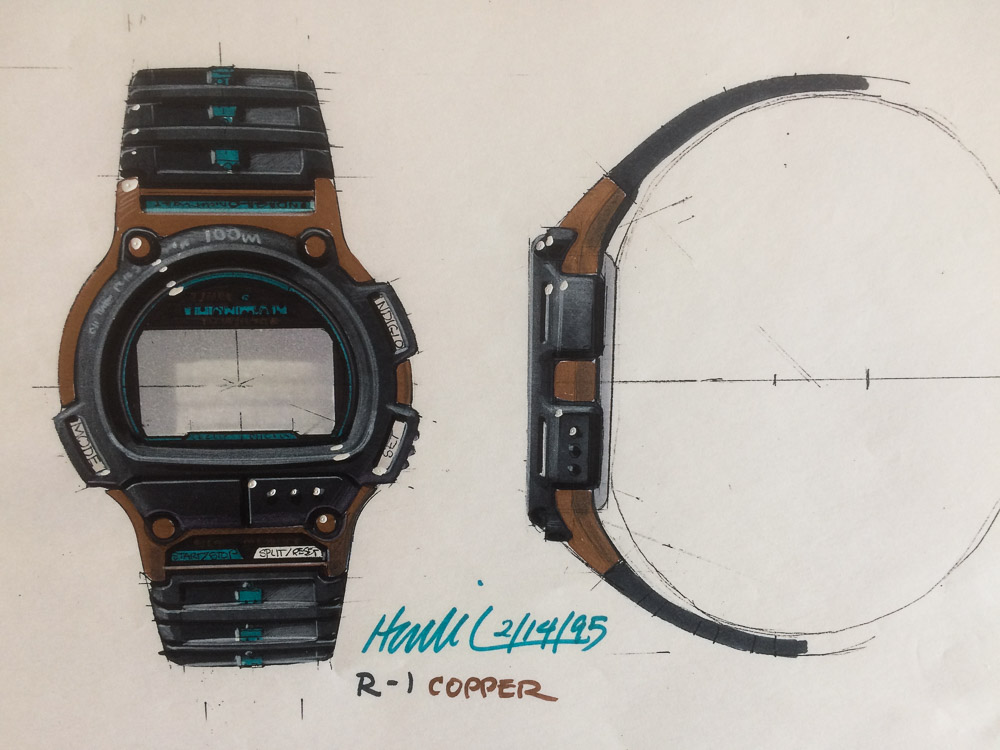

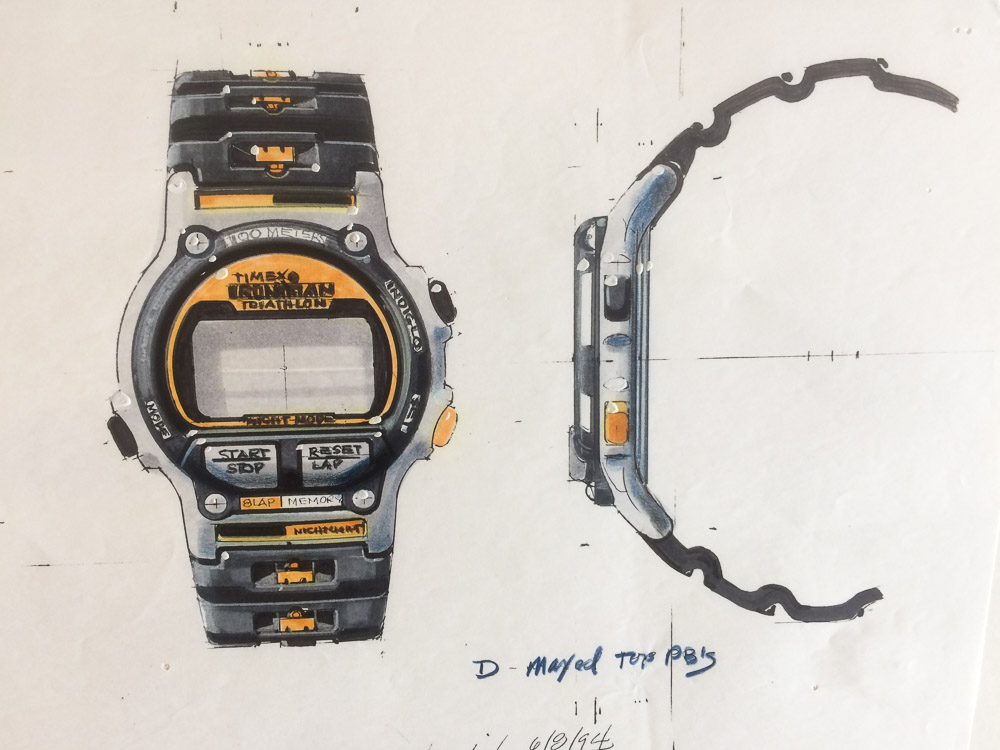

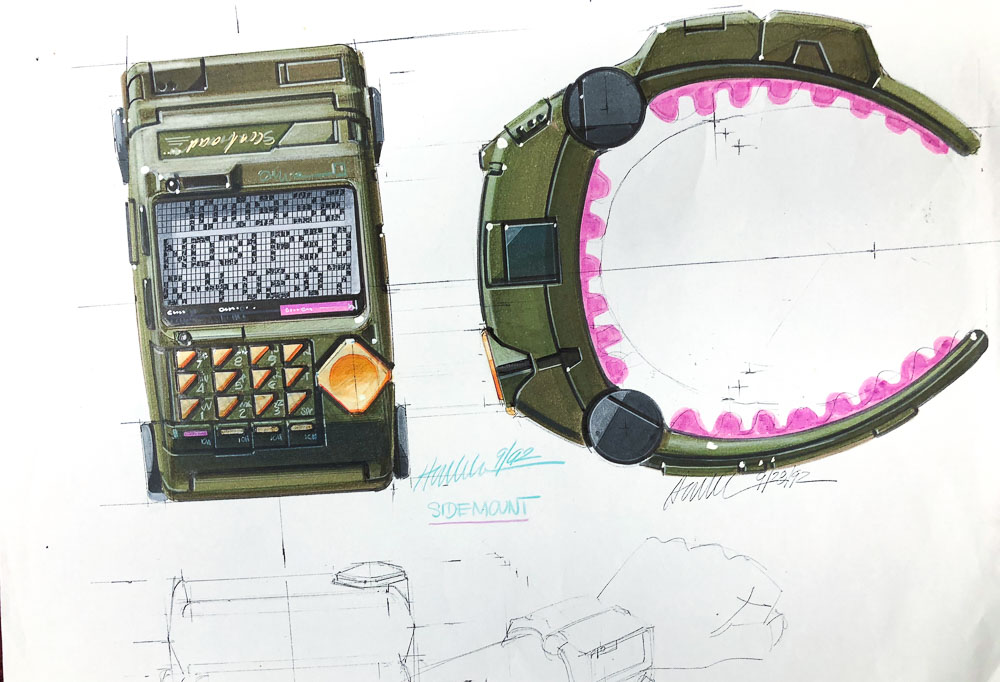

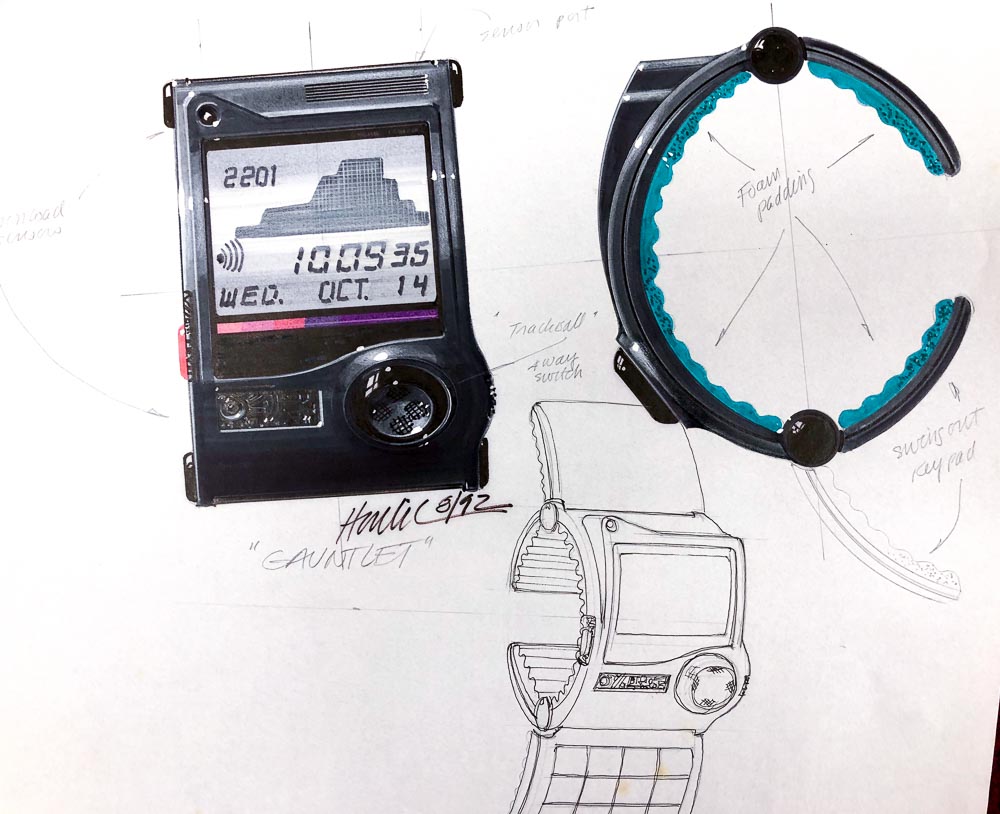

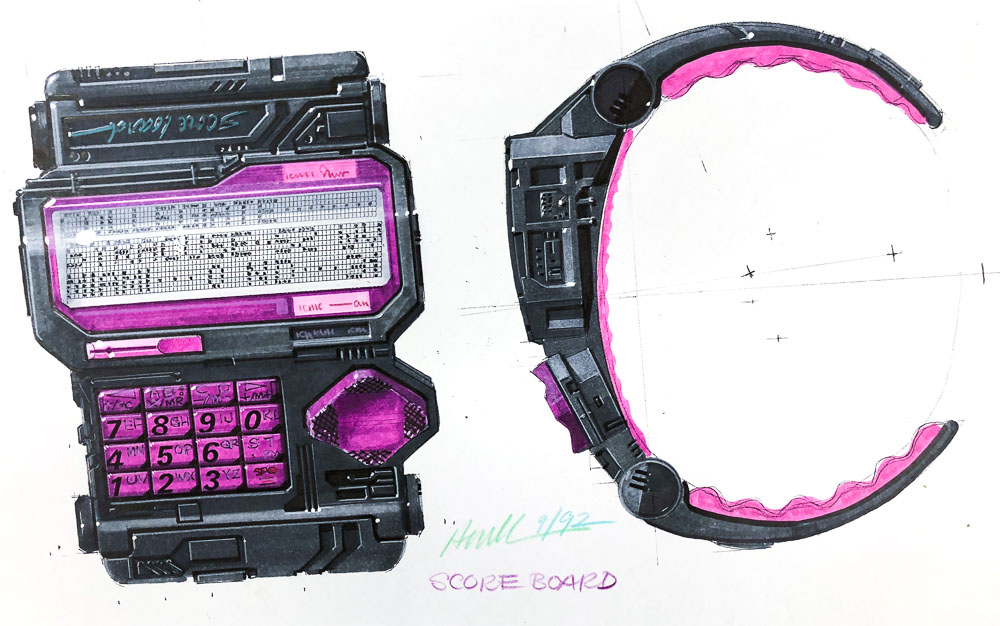

John sent me a great number of exciting and innovative sketches from his work at Timex. I couldn’t edit them down, so here are all of them. His biography records his fascinating journey through very different design environments and disciplines.

John’s Amazing Career

GENERAL MOTORS 1966–1970

General Motors Styling Staff in 1966 was the paramount automotive design job in the Detroit area. Located at the GM Tech Center on Mound Rd. in Warren Michigan, more than a staff of 1000 provided the design for the entire US line to cars offered by GM. To have started my career at this place was beyond lucky. It was at GM where I really learned to be a designer. I consider the experience at GM Styling the equivalent of earning a Master’s degree in industrial design.

While I value my education at the University of Notre Dame, the studio training experience there was not at the level of many other universities offering industrial design but especially schools dedicated to design training such as Pratt, RISD, or especially, Art Center. ND did have a dedicated, automobile influenced, industrial design concentrated major within the Art Department. Located in an “attic” in O’Shaugnessy Hall, the Chrysler Corporation provided the funds to refurbish, air condition, and provide drafting tables and other design fixtures to conduct a proper design education effort. Chrysler Design was then headed by Virgil Exner whose son had graduated from the university in the mid ’50s. Exner influenced Chrysler to support the university thus the automotive slant in the design department.

Ford, GM, and Chrysler sent representatives to interview prospective hires throughout the late ’50s into the ’60s and beyond. In my particular case, Bob Veryser from GM interviewed me and some of the other students in early ’66. I, along with another ND student, received invitations to interview with GM Staff at the Tech Center later in the year. I am forever grateful to Mr. Veryzer, Roger Martin, and Charles Jordan for granting me the offer to join the Styling Staff. I knew at the time that GM was overlooking my obvious technical shortcomings in the area of professional artwork skill seeking to get a designer with the “more rounded” education a university such as Notre Dame provided.

While at GM Stying I was able to learn from the most talented car designers in Detroit and, perhaps, the world. The late ’50’s into the early ’70s is a period of time now considered the “Golden Era” of car design. The work done by this collection of talented designers was and is awe inspiring. I am grateful to the individual designers who coached me along. They include: Dave North, Bernie Smith, Dave Rossi, Gordon Brown, Charlie Jordan, and several other designers whose names escape me.

SCM (Smith Corona Marchant) 1970 –1971

Two main reasons I left GM are:

1. Not fond of the Detroit area, especially the north east section where we lived. First, Roseville near 11-mile and Gratiot, then Clinton Township/Mt. Clemens near 16-mile and Groesbeck Hwy. We may have stayed longer, or even permanently had we located in a suburb on the west side, Rochester comes to mind.

2. Staying at GM or any automobile design environment meant being typecast as a “car” designer by those outside the automotive world and not suitable for the product design environment. This is, of course, completely not the case. A good car designer is equipped to design any product while a good product designer will not be able to design, successfully, cars until they understand the scale of the product. It takes time and practice to gain a feel for the proportion of the various elements of a car’s makeup so that even the quick sketches will evoke a realistic and credible image of the idea sketched. Then there’s the artistic skill required to evoke the excitement and energy needed to capture the emotion of the viewer. These skills are honed in an automotive design environment.

SCM Corporate ID center was a classic corporate design environment. There were talented designers there, a model shop with a great paint shop facility and an environment of camaraderie. While the negative attitude toward a former car designer existed in some of the other designers the overwhelming response to my work was positive. They appreciated the enthusiastic approach to sketching and rendering I used to communicate my ideas. I learned a lot about packaging the mechanisms, making models, and meeting with corporate marketing personnel. It was a good experience cut short by a large, financially necessitated layoff. Although I was the newest hire, I was not laid off. I guess my sketching skills acquired at GM paid off. Relieved as I was to still have a job my confidence in SCM’s future was shaken. I looked for another opportunity.

GENERAL ELECTRIC AUDIO ELECTRONIC PRODUCTS DEPARTMENT 1971–1978

Fortunately, GE had a few large establishments in the Syracuse, NY area. Among them was AEPD (Audio Electronics Product Department). This too was a classic corporate design environment equipped with a full model shop and paint department. One difference here was designers were not allowed to touch the machines or spray booth tools. So we relied completely on artwork (sketches, renderings, drawings) to communicate our ideas. This office was also an animated, lively place to practice design. There were a few really talented designers who could inspire the group to better effort.

It was at GE that I had the opportunity to visit several Far East countries where products were sourced. A team consisting of Marketing, Engineering, and Design would visit various vendors or GE facilities located in Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, and even the Philippines. Some of these sourcing trips lasted 3 to 4 weeks. This was a great learning experience in what is involved in design, engineering and manufacturing a product. We took it from quick sketch to first production at GE. Marketing had the helm calling shots involving feature content, pricing, scheduling and cost. Industrial Design’s responsibility was to create an appealing product visually along with designing a good user interface. Engineering was responsible for the technical aspects concerning the mechanical and electrical details and manufacturability of the product. This approach usually worked well. There always is a tension among Design, Engineering, and Marketing which forces one to “work and play well with others.” This is, of itself, a valuable skill to learn.

TEXAS INSTRUMENTS 1978

Designers often seem to be nomadic, always looking for the next best opportunity, at least I was, so I took what seemed to be a terrific position at Texas Instruments in 1978. Problem was, I didn’t think it through very well. Sure the job itself was challenging, the product was new and interesting but I did not evaluate the location. Lubbock Texas, located on what’s called the south plains of Texas, was a totally different geographic environment, The West Texas culture too was unlike anything I had ever experienced. It was a disastrous mistake. I lasted eight long weeks. I had to leave.

SOUTH BEND TOY, Division of MILTON BRADLEY 1978–1979

With the help of my dad who was a Vice President of Development at Milton Bradley in Springfield, Massachusetts, I was able to secure a position as design manager in new toy development at South Bend Toy in South Bend, Indiana—home of my alma mater. That alone was a reason to move but the new challenge of toy design was intriguing. At that time this company was primarily involved in the manufacture of croquet sets and doll carriages. Management at Corporate HQ in Springfield, MA wanted the company to get into “toys” the way Mattel, Kenner, and other toy companies were focused. Initially, i was fascinated in this interesting arena, one where an Industrial Designer can rise to the top levels of management. Then I eventually realized that the value of aesthetics, form, sculptural nuance, other artistic factors was not emphasized in this business. Instead, unique clever features, play value, child safety, and other non-styling elements were the key factors in design. These are all valid qualities uniquely contributed by industrial design, just not what motivated my “muse”. I guess I wasn’t a “toy guy.” Other aspects of the business centered on the financial issues involving advertising and licensing. The toy buyers were far more interested in how much advertising money was earmarked for a given item, or be promoted on a TV commercial and whether or not it would have a popular license (Disney, Star Wars, etc). What that meant in the end was a great, clever item with low ad commitment, no TV promotion or no license would die on the vine where a mediocre item would be bought by the major toy distributors and sellers even though the toy lacked play value or innovation. I gave the business a solid effort, successfully sourcing new products in Hong Kong and working the Toy Fair with the results of that effort. But, I realized this business was not for me as a designer. Again, I began a search for another opportunity.

TIMEX 1979—2001+

Ritusue Siegel (design placement agent) found the next job opportunity. I was contacted by her in mid 1979 regarding a design manager position at TIMEX. More interestingly, the new Director of Design at Timex, John Maliskas, asked for me by name. We had worked together at GE in Syracuse. This position was located in Middlebury, CT so I was very interested in checking it out. I admit, I was a bit concerned about the world of jewelry, watches and the like and how I would relate given my prior experiences in automotive and product design. What I found was the world of watch design and the product itself was fascinating. Ironically, watch design turned out to be the closest thing to automotive design in all my experience.

First, scale is critical to the creation, communication and execution of the design of an automobile. It took more than a year for me to get a feeling for the scale of an automobile so that my sketches and other visual communication looked accurate and believable on paper and resulted in a well proportioned design in full scale. Scale, too, is crucial in the visual communication of watches. The sketch needs to address the fine relationships of the elements of the watch case where fractions of millimeters can make a difference in appeal to the eyes. Since watches are small, sketches are usually done two times or even larger that actual size. This means the designer is working larger that the final product and has to have a genuine feel for the proportion of various parts and elements of the design. Most designers attempting watch design for the first time fail to grasp the scale challenge. So did I. It took time for me to achieve a real understanding of this scale challenge.

Sculptural aspects of the design challenge are similar in both automotive design and watch design. The product is three dimensional. While that should go without saying, a lot of the product design with which I was involved was largely two dimensional, that is, a box with high relief. Some products, such as the adding machines at SCM and a few of the audio products at GE were more three dimensional, none held the sculptural challenges of automobiles and, yes, wrist watches. Additionally, wrist mounted product involves ergonomic issues and challenging user interface complexities. Watches, digitals in particular, have multiple control procedures requiring the user to activate function via push buttons, sometimes two at a time. Conveying ideas two dimensionally via sketches, drawings, and renderings is not unlike the design sketches for automotive work. Knowing what the product will look like from various views requires a lot of experience both in the world of cars and watches.

Third, styling—the aesthetic presentation—is paramount in creating successful automotive and watch design. People react first to the look of the product. If there is no positive visual connection there is no sale. The customer has to have an affinity for the way the product looks. Creating the striking, unique and well executed design is, perhaps, the biggest challenge in designing a successful product, it is also the most satisfying.

So, I was finally at home in a design environment that matched my ability and interest. I stayed at Timex for over 20 years. To be sure it was challenging. I rose to the level of Director of Design World Wide with offices in Middlebury CT HQ, Cebu, Philippines, Hong Kong, Besancon, France, and London, England. There were over 40 employees working at these locations on product design. Oversight involved quite a bit of travel which was arduous and even exhausting. The satisfaction came when successes in the marketplace helped the company survive in the face of intense competition from the Far East.

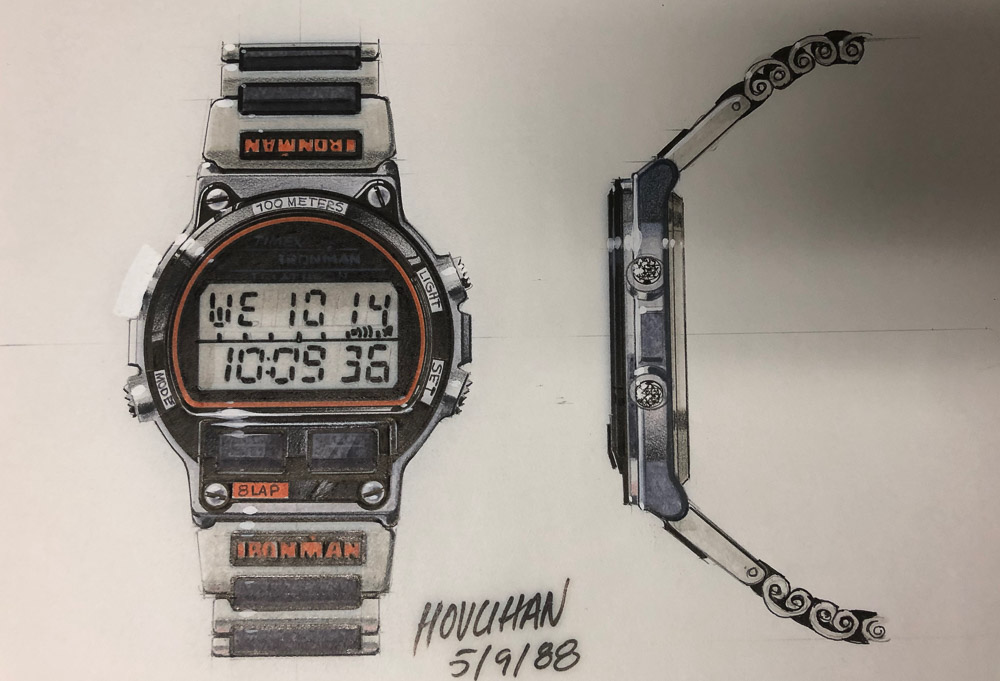

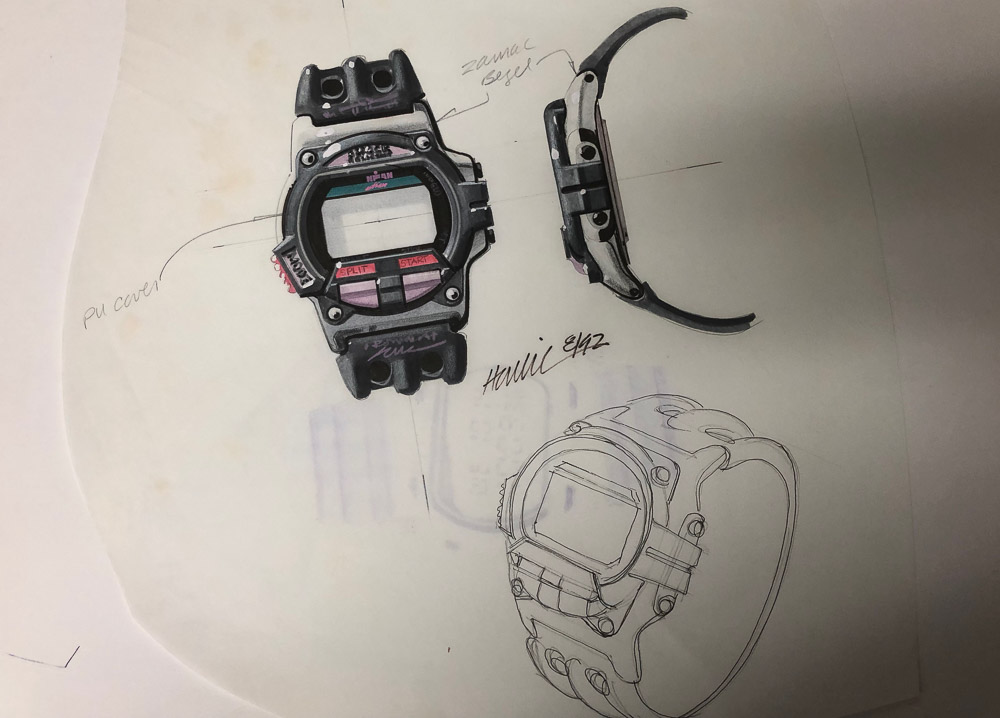

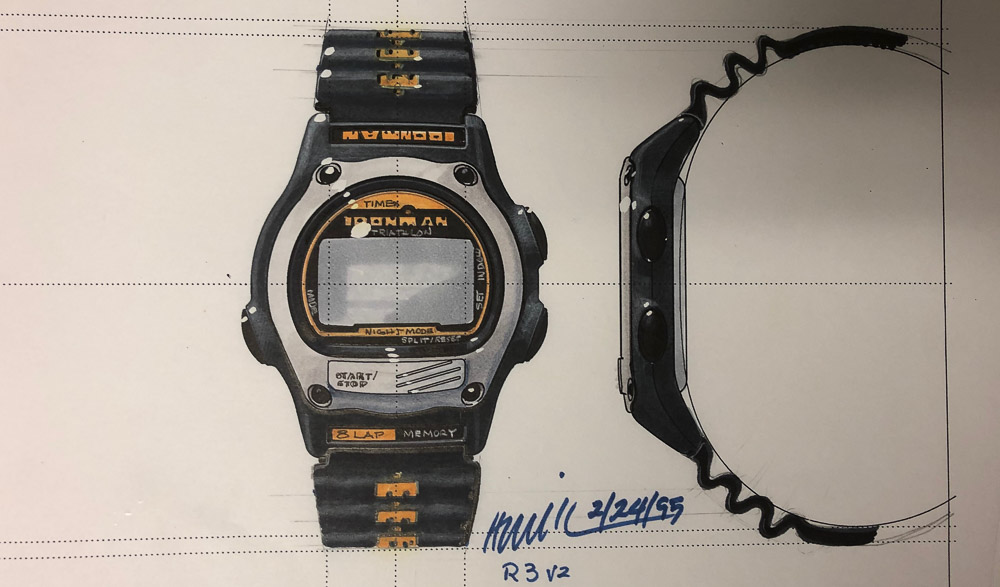

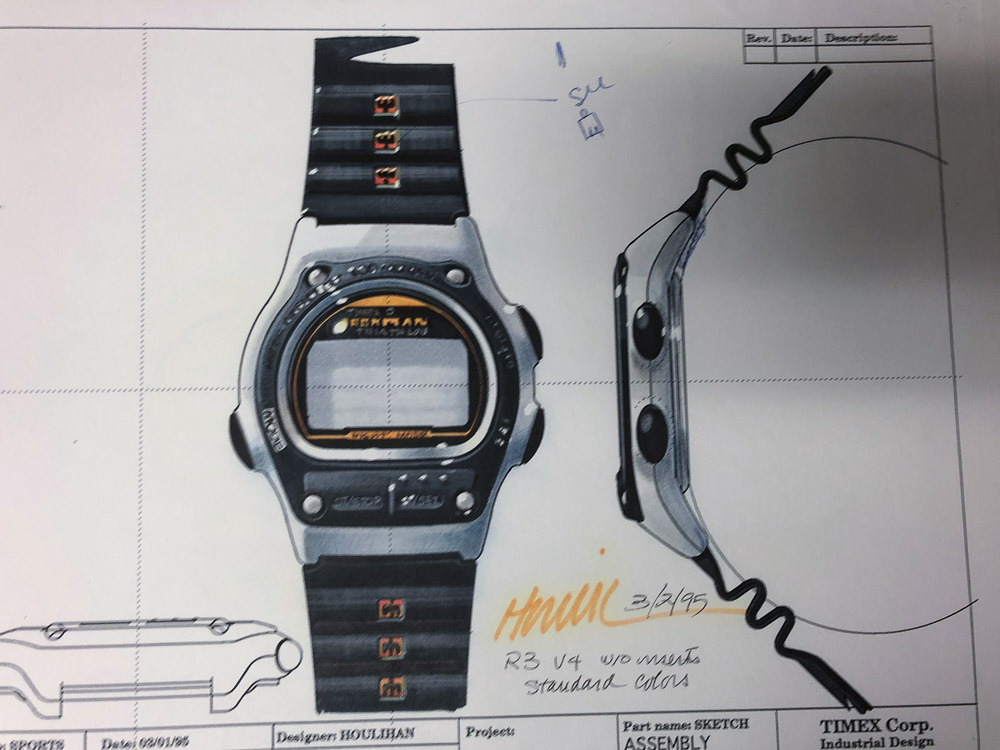

The best example of this success is the IRONMAN Triathlon watch. In conjunction with the product planner Mario Sabatini, who had promoted a marketing connection with the World Triathlon Corporation, the TRIATHLON watch was developed using a new, top mounted, push button design which activated a novel lap memory system for runners to use while training. The IRONMAN Triathlon watch embodied this system and used the IRONMAN logo and name. The IRONMAN Triathlon, especially the one held in Kona, HI, became recognized as the quintessential endurance race in the country.

At the time the first Triathlon watch was introduced, digital watches were considered cheap, almost throwaway, timepieces. Cost was the key factor in their design, manufacture and sale. Japan, Casio in particular, owned this business and it was having a real impact on Timex sales. When the Triathlon appeared on the market it was three times the price of the usual digital watch and had an unusual appearance given the two large face-mounted push buttons. Many in the sales and marketing group were skeptical that this product stood a chance of selling at all. It sold, more than any other digital watch in the line. Then, a year later, when the IRONMAN Triathlon watch was introduced with a gray metallic (an automotive paint color) case, orange color accents and I-M logo it took off to become the largest selling single style in the history of horology. This was a magical combination of smart, innovative product development, shrewd advertising promotion, sharp licensing connection and bold, impactful styling. This product turned the corner for Timex and pulled them out of the sales doldrums of the mid ’80s. The IRONMAN brand continued to grow to an entire line of products that sell well to this day.

There were many other design successes and failures too numerous to list and explain. The experience of designing these products, working with the various elements of the process (engineering, sales and marketing, manufacturing) and with other entities around the world created an amazing opportunity. The design group was diverse, talented and hard working. I was very fortunate to be associated with these fine designers.

John T. Houlihan 5/19

Many thanks John for your story and the excellent (and creative) watch design concepts. I found myself studying each concept, then looking forward to seeing the next with anticipation and surprise. Many designers can create a sketch of a design concept and show 100 variations of it…you have the rare talent to create 100 design concepts and show all of them with professional flair and conviction.

It is a shame that you left GM when you did. They needed your creativity in the 70s.

Most car designers do not appreciate how hard it is to become successful in product design. Many have never had the experience nor education to develop the engineering, marketing, and manufacturing requirements required, You met the challenge and thrived. I’m reminded of my interview with Henry Dreyfus jn Pasadena after I left GM…”Sure you can style cars, but what do I need with a car stylist?”. Most insightful comment of my career. So I went down the street to Keck/Craig Associates and got a job as the only ID guy in an engineering office for 1/3 my previous GM salary. It was a crash course in the realities of product design. Forty years later, I retired from my company as a product designer.

Very impressive work from my perspective.

Bravo John!

Amazing work!

I believe the majority of transportation designers leave the field after either a few short years, or after experiencing what the job really entails. Still others hang in there until they are asked to leave or survive into retirement (a rarity these days!). Being native Californians, we never adjusted to life in D-Town, the lack of culture and winters drove us out! I’ve been lucky enough to have found work in trans, product and fashion design here in LA. I’ve travelled globally and loved it! There is life after car design!

JOHN,

Remember working together, in Overseas Studio, I think. I am glad you found a fruitful outlet for your creativity. I have done product design, graphics and car design. As an experience, my greatest satisfaction was working with a large skillful and professional team on a dynamic product that I could later drive.

I am now working with a watch company, great fun!

All the best, you were a great guy to work with.

DICK RUZZIN

John,

It was fun working with you in the Advanced Pontiac Studio under Gordy Brown too many years ago. Your creative talent has served you well throughout your career, and the fine comments by your peers above give testimony to your talent and accomplishments…

Thanks for sharing the amazing battery of your work, and it’s great to see all your hand drawn images…

John M. Mellberg

HEY THERE JOHN–ITS PETE MAIER

I BELIEVE THE LAST TIME WE SPOKE WAS IN THE HALL IN FRONT OF ONE OF THE ADVANCED STUDIOS THE DAY I RETURNED TO STYLING FROM VIET NAM IN THE SUMMER OF 1969—-I RECALL ALL THE GREAT TIMES WE HAD TOGETHER IN DESIGN DEVERLOPMENT THE SUMMER OF 1966 WITH FELLOW ROOKIE DESIGNERS LIKE TOM HALE–CHARLIE GATEWOOD– JOAN KLATIL –BILL MICHALAK–RANDY WITTINE–JERRY PALMER ALONG WITH THE GREAT DAVE ROSSI–BOB VERYZER–AND OF COURSE CHUCK !

ALTHOUGH WE HAVE NEVER REALLY KEPT IN TOUCH OVER ALL THESE YEARS I JUST READ YOUR WRITEUP ON GARY’S DEANS GARAGE SITE—VERY INTERESTING CAREER YOU HAVE EXPERIENCED & CONCISELY WORDED–GREAT SKETCHES MY FRIEND–WISHING YOU THE ABSOLUTE BEST —PETE.

As a former car designer who’s been designing lots of things that aren’t cars for 16 years, I love this. Thank you for sharing all those awesome sketches, they’re the sort of thing that inspired me to actually do this for a living.

I deeply miss the marker and pencil era, despite how thrilled I was, and still am, about the possibilities that digital sketching provides.

I enjoyed reading your story. I went through a similar phase of leaving GM for California to do product design in the early 1970s. Fortunately for me, with my experience as a car designer, and my GM resume, I found work in automotive toys. I eventually went back to GM design, missing concept work. I admit I’m not a good product designer, and had few opportunities to try for it.That’s a different mind set from the sculptural possibilities of car shapes. Product designs are much more closely related to their function, while cars express motion and emotion. Congratulations on really fine work.