Ford’s Mustang Mach 2

by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

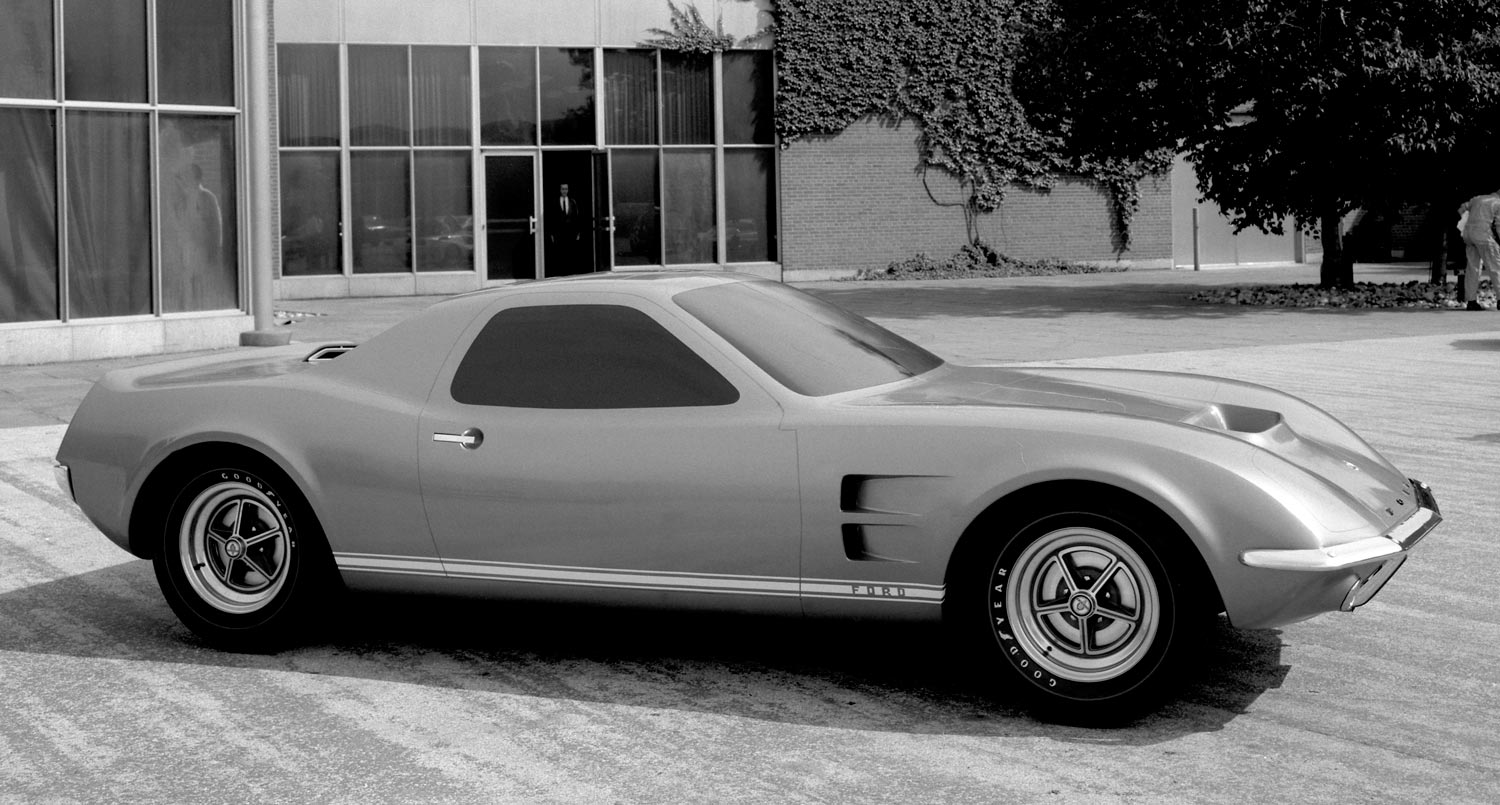

The 1960s were a heady time for Ford. In 1962–3 Ford developed its small block V-8 engine (later used in the Mustang) for racing use. In 1964 that engine got double-overhead-cams—for racing only. In 1965, a Lotus powered by a highly-modified small block Ford V-8 engine won the Indy 500. From 1966-69, Ford won the 24 hour race at LeMans four years in a row. Not only was Ford’s racing program doing well, Mustangs were selling like hotcakes! The double success of Ford racing and the Mustang led to a concept car called the Mach 2. It was a proposed mid-engined, two-seat sports car.

The Ford personnel most responsible for development of the Mustang Mach 2 were Lee Iacocca, Gene Bordinat and Roy Lunn. Iacocca became general manager of Ford Division in 1961. Because of the runaway success of the Mustang, he was placed in charge of all of Ford’s cars and trucks in 1965. Bordinat, who started at Ford in 1947, became Ford’s Chief Designer in 1961. Lunn, who started at Ford of England in 1953, came to the U.S. in 1958. He eventually became head of Ford’s Advanced Vehicle Center, and was deeply involved in the final development of the Mach II as a road-ready car and also as a potential race car.

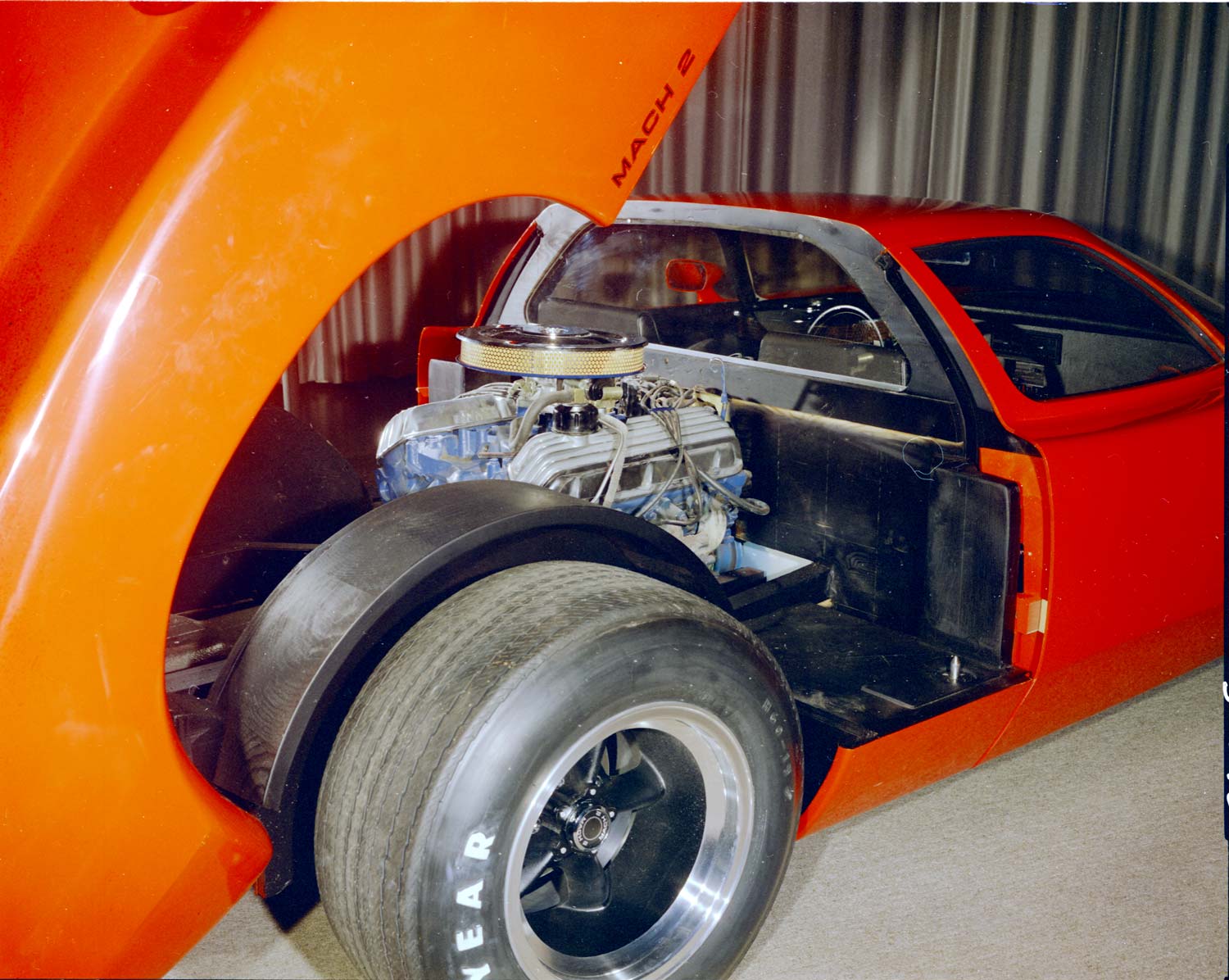

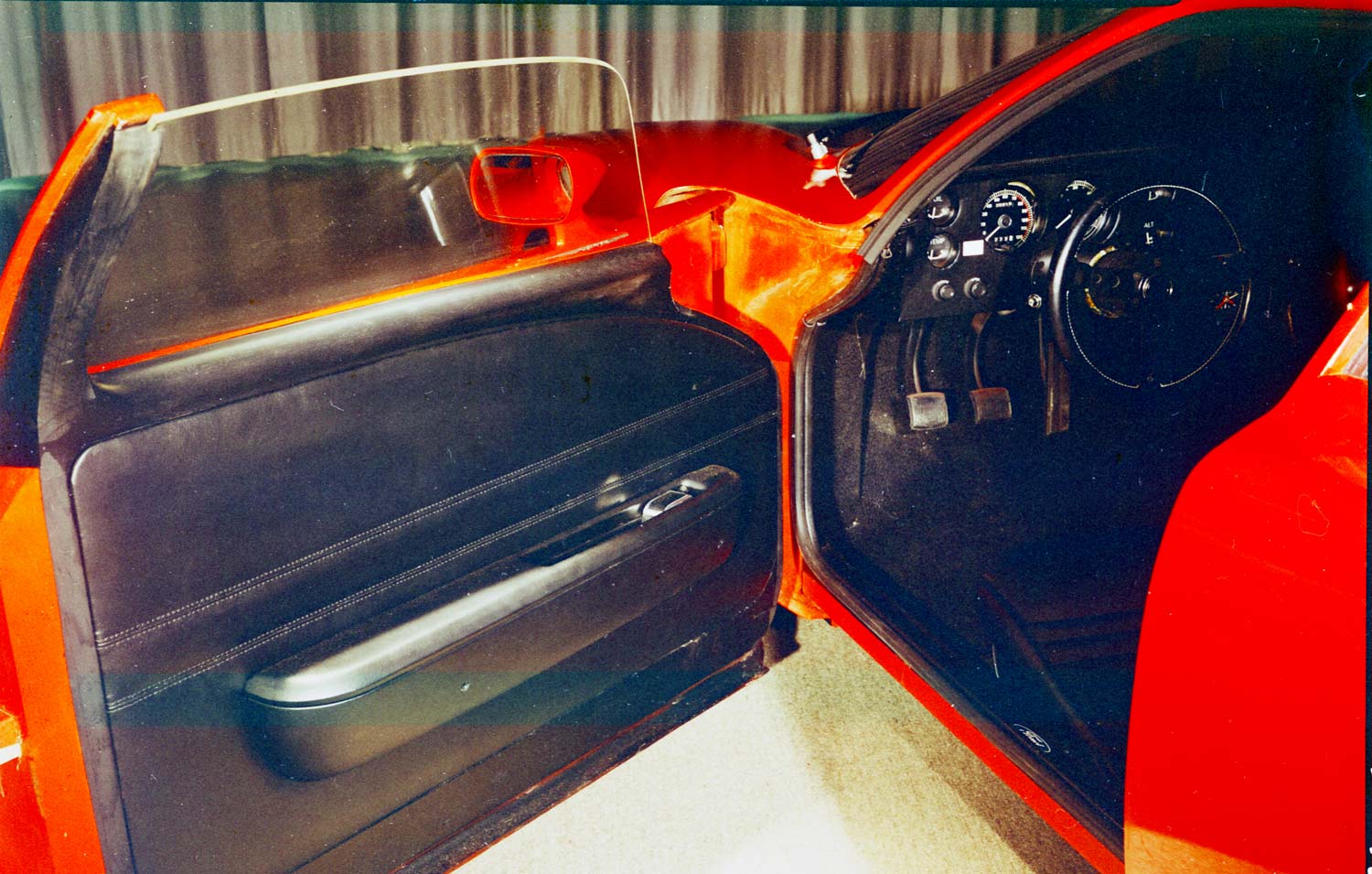

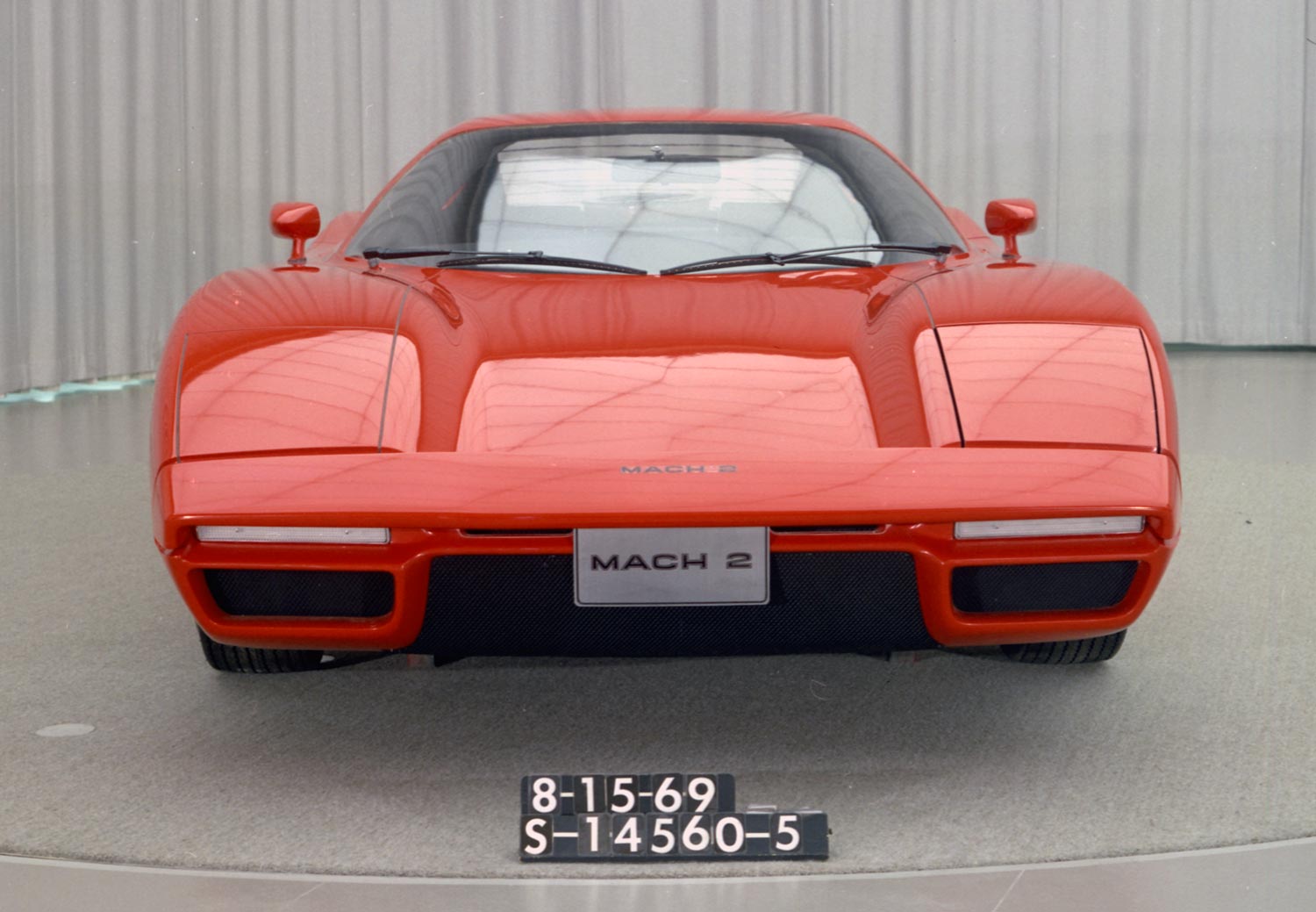

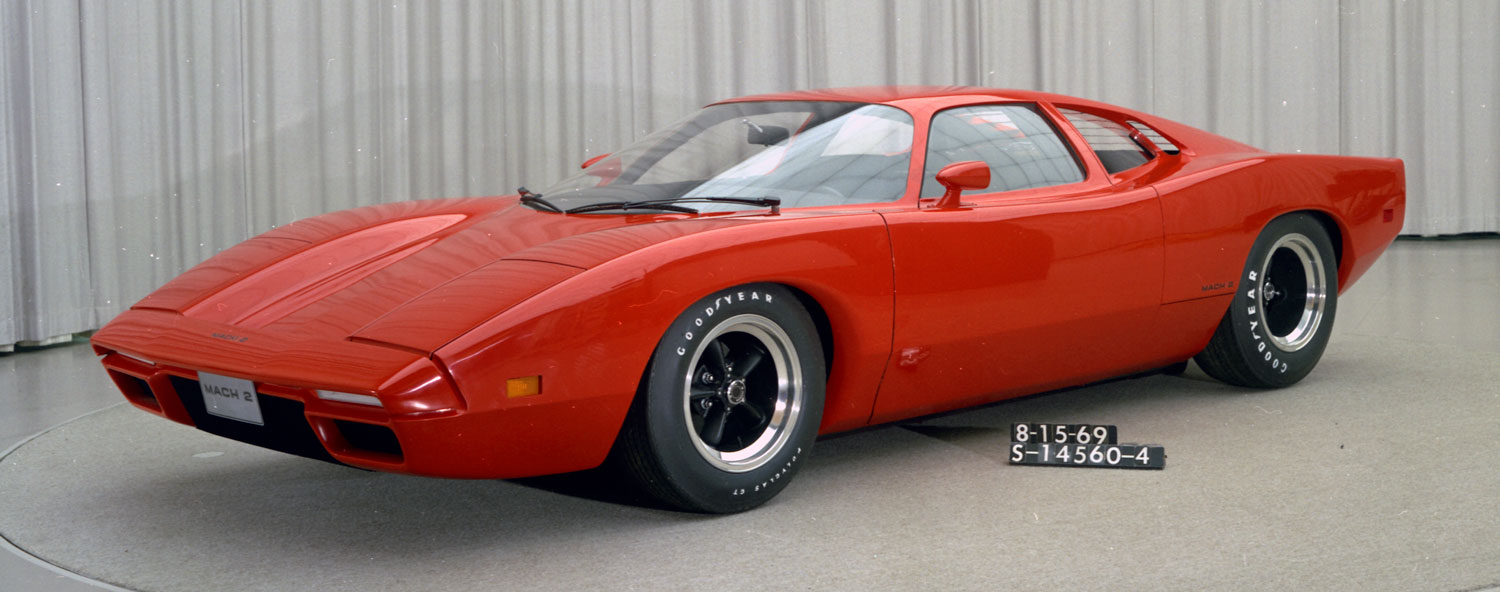

Whose idea it was to build a mid-engined sports car from a Mustang is lost to history. From a design standpoint, however, the project got started in early 1966. Bordinat assigned the project to the Corporate Projects Studio. According to designer Bud Magaldi, Jerry Morrison was the primary designer working on the Mach II. Magaldi had recently been hired, and working on the design of the Mach 2 was one of his first assignments. Morrison and Magaldi worked with a talented design engineer named Bob Huzzard who got his start during World War II designing autogiros. Huzzard went on to become a designer at both Hudson and Briggs Manufacturing before switching to design engineering at AMC and then Chrysler. He came to Ford in February 1964, and was immediately assigned by Bordinat to the Corporate Projects studio as a design engineer. Morrison and Magaldi designed the outside of the Mach II, while Huzzard was the one who engineered a ‘66 Mustang into a mid-engined sports car with independent rear suspension.

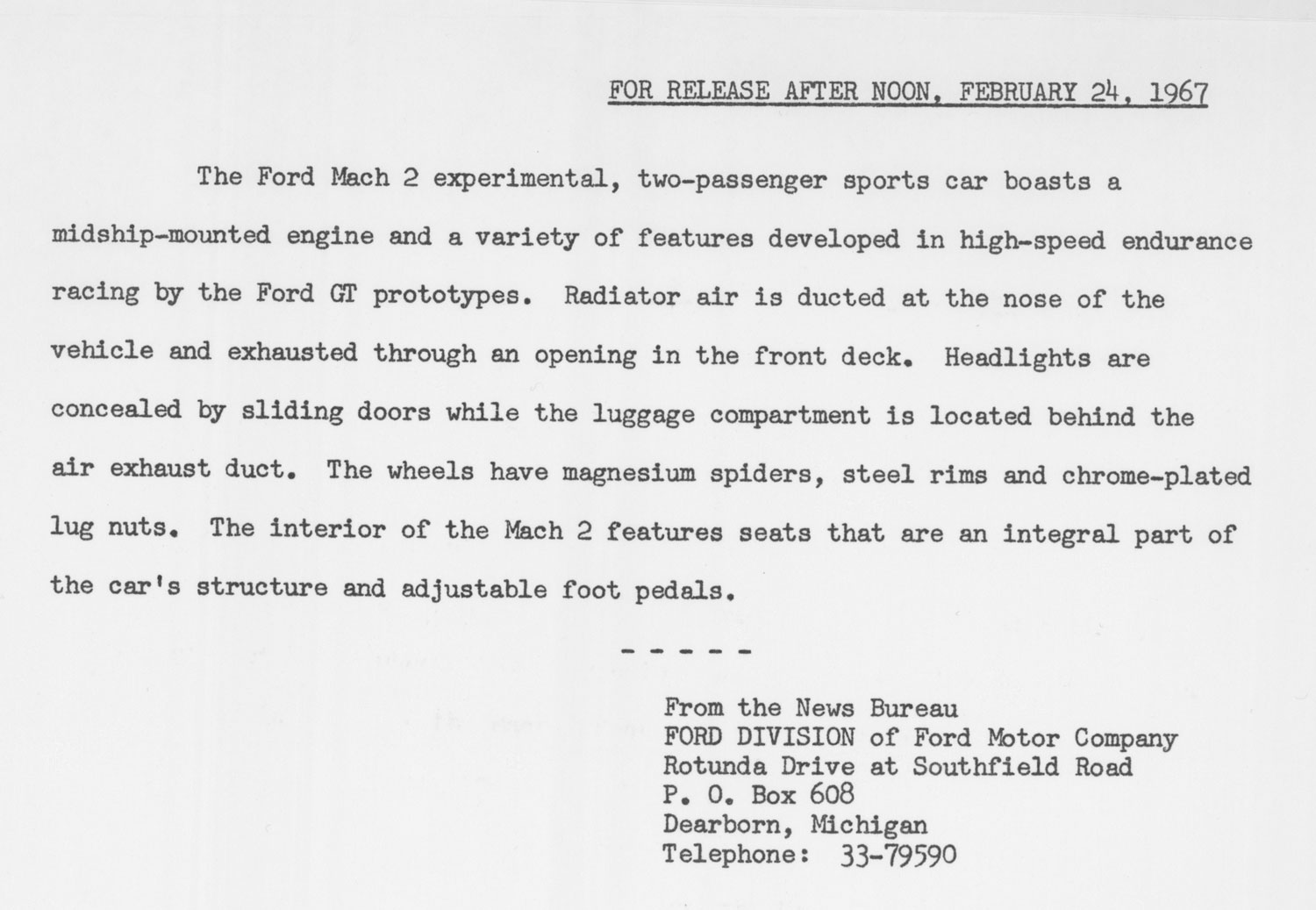

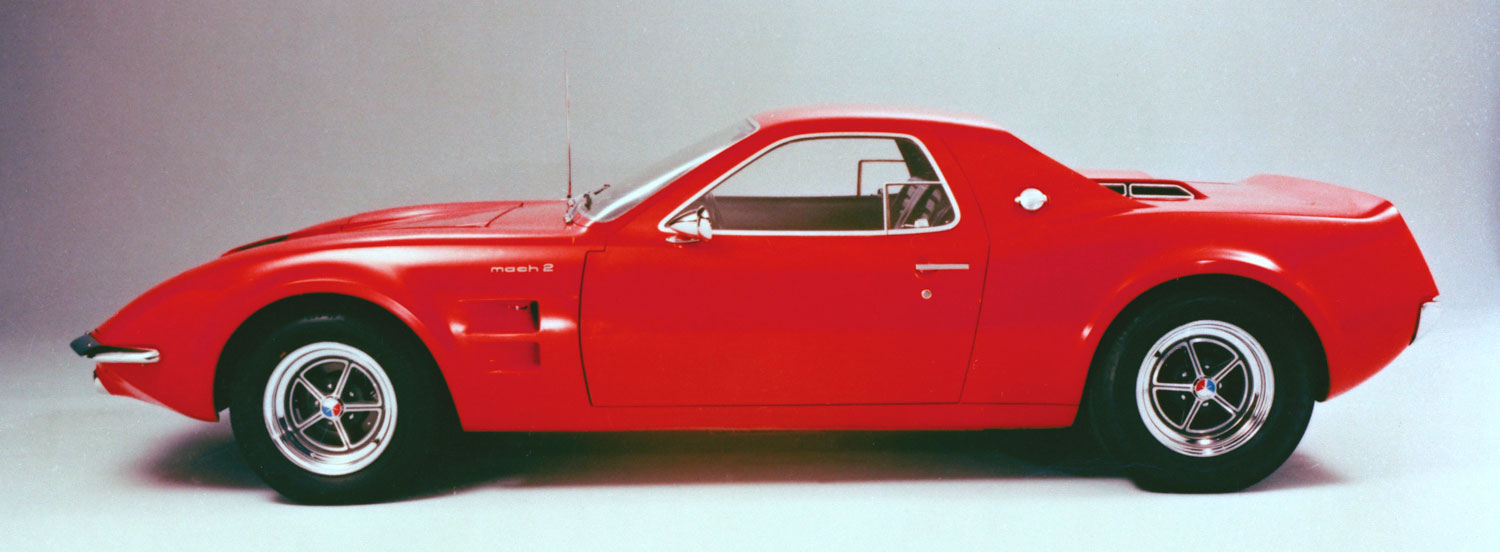

Design and engineering work at Ford’s Design Center was completed by early 1967, and the Mach II was then moved to Kar Kraft, a local job shop set up by Lunn for Ford, where it was finished into a street legal car. Kar Kraft actually built two operable Mach 2 sports cars (red cars) and one race version (white car).

According to Ford, the Mach 2 had a wheelbase of 107.3 inches, weighed 2,650 lbs, was powered by a 289 CID mid engine and had doors that “opened high into the roof.” The car was a big hit at the ’67 Detroit Auto Show. Sometime after 1967, Ford determined production was not in the cards, supposedly because of the car’s complexity and the costs involved. Until 1970, the red cars were often featured in parades and other events in the Dearborn area. The race version Mach 2 was eventually crushed, and the two sports car versions of the Mach 2 disappeared sometime after Kar Kraft shuttered its doors in late 1970. Maybe they were crushed, maybe not, but there’s a postscript to the story.

In spring 1968, Henry Ford II hired Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen away from GM to become Ford’s president. Knudsen got the job Iacocca wanted. When Kundsen came to Ford he brought two GM designers with him. One was Larry Shinoda of ‘63 Corvette Stingray fame. Shinoda and Bordinat didn’t get along. Shinoda ignored Bordinat, and looked to Knudsen for protection and directions. In other words, Shinoda only did the design work he and/or Knudsen wanted. One of the projects Shinoda undertook was to revise the Mach 2 concept into Ford’s answer to the Corvette, including provision for a big block engine in a substantially revised Mach 2, now called the Mach II. To make a long story short, in September 1969, Iacocca, Bordiant and others Ford executives were successful in getting Knudsen fired. Right after Knudsen was fired, Bordinat placed a call to Shinoda, who was in Germany attending an auto show. Bordinat told him he too was fired, and he needed to return to the U.S. quickly because his company credit card was being canceled. So ended Ford’s Corvette challenger called the Mach II.

Posted by permission.

Photos courtesy of Ford Archives.

From Ford Design Department—Concepts & Showcars, 1932-1961 by Jim and Cheryl Farrell

ISBN 0-9672428-0-0

Book review to come.

For book ordering information, email: cfarrell57@gmail.com

It certainly was a far “cleaner” design than the over-worked but under-done, as my best ACCD instructor would say, than the C8 Corvette! Maybe a bit too clean, but better than a “explosion in a mattress factory,” another of Ted Youngkin’s favorite descriptions……. 🙂 DFO

I remember seeing the 1966/67 version in magazines when I was a kid. The design variations are interesting but the version that was released looked good for the times. I remember liking the signature large round taillights set into the rear panel as pictured. I don’t recall ever seeing the ‘69 design, presumably by Shinoda. It looks ahead of its time and much more modern than its predecessor. Also, it is quite bizarre to read the description of the relationship between Shinoda and Bordinat. What a work environment that must have been.

It is interesting that they let the Italians do the Pantera. I was in Monte Carlo for the race in 1971 when we saw several Panteras being driven around the city at night. I think it was launched there. It looked exaggerated compared to the Mangusta but it was a strong and unique statement. Two very different approaches, equally valid.

The design culture at Ford really focused successfully on the Mustang as an American sports car and then a muscle car through the years. But with so many mid-engine cars released at that time, production and concepts, the artistic, or sculptural character of this car is rather weak from a design standpoint, probably because the designer was inexperienced. That was the real strength of the Italians along with a real understanding for the “Racecar for the street”, starting with the Ferrari Barchetta. Those 1/10th scale drawings that they did required something big to be done or you just wouldn’t see it. They could also very well match the look with spirited performance.

The Corvair Monza GT came out in 1964 and was a very sophisticated form study with an advanced platform that was shared with Jim Hall.

I think it also influenced the designs of the Italians. It was done in Studio X but Larry Shinoda had a lot of help that he did not have at Ford.

In all fairness to Ford the designers were just not close enough to the racing effort of the Ford GT as GM designers were with the Corvette and the work that followed at Engineering Staff and Chevrolet R&D. In the Chevrolet Studio at Design we could hear a big block running flat out a quarter mile away in one of the Chevrolet test cells. And then there were the strange and repeated downshifts that kicked it up another excruciating notch every time. The internal excitement from the Ford GT did not transfer to the designers of this car.

There is a little bit of Bizzarini Strada in this car also but without the music.

Dick Ruzzin

Yet another good idea that would have advanced the American sports car story many more pages than most of the pedestrian run-of-the-mill stuff Ford fed us instead. I mean, park either of these cars next to a Mustang II…and as for references to the Monza GT, where exactly was the street version of that car, again? I must have missed it.

Of course you missed it.

It was very small and was parked on the other side of the street version of both of the Mustang concepts in this article.

You can see the design influence of the Monza GT in the Detomaso Mangusta and the Lamborghini Miura. Also Jim Hall’s Chaparrals.

Dick Ruzzin

Roy Lunn was the father of the car line AMC Eagle.